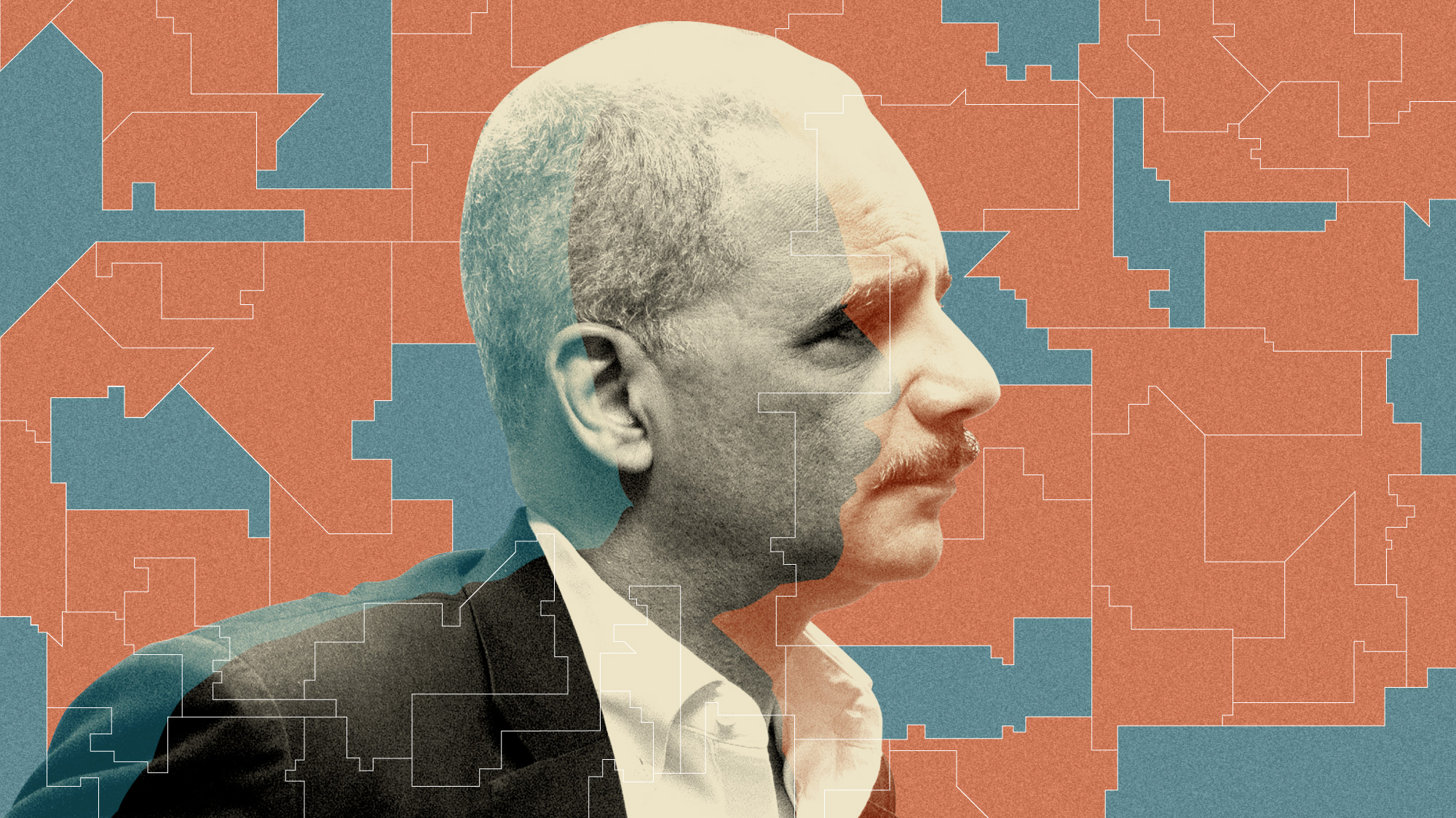

On a frigid March morning, Eric Holder strode into a brick union hall on the west side of Milwaukee, across from a credit union and an auto body shop. The Merrill Park neighborhood was once the center of the city’s Irish political machine, filled with stately Victorian houses—including the childhood home of Spencer Tracy—but it was now mostly African American and economically depressed.

Holder had dressed down from his usual suit and tie: He wore a black fleece jacket, white button-down, and dark blue jeans. He was warmly greeted by Angela Lang, the 29-year-old executive director of Black Leaders Organizing for Communities (BLOC), a local group that works to increase voter turnout in Milwaukee’s black neighborhoods from an office in the union hall’s basement, which was filled with campaign flyers and maps. It was the 68-year-old former attorney general’s third visit to Milwaukee in a year, and Lang addressed him as “our No. 1 cousin.”

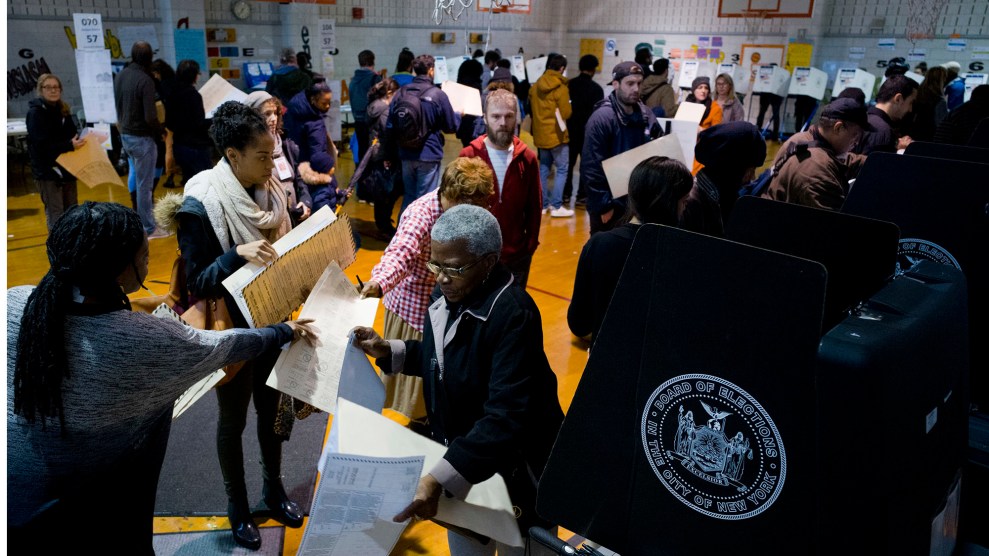

The reason for Holder’s visits was Wisconsin’s assault on voting rights. The Wisconsin GOP had passed a voter ID law, designed to depress Democratic participation, that took effect before the 2016 election. As a result, turnout in Milwaukee’s black neighborhoods dropped by more than 20 percent.

Not long after the election, Holder launched the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), a political action committee that aims to unrig the system that has entrenched Republican control of the country’s most important swing states. He’d received the backing of top Democrats, including former President Barack Obama, who in December 2018 folded his own political operation, Organizing for Action, into Holder’s to give the fight against gerrymandering more clout. Now, while other top Democrats are focused on the White House, Holder has set his sights on neighborhoods like Merrill Park and on races like the one he was there to talk about, a state Supreme Court contest that had received virtually no attention outside Wisconsin.

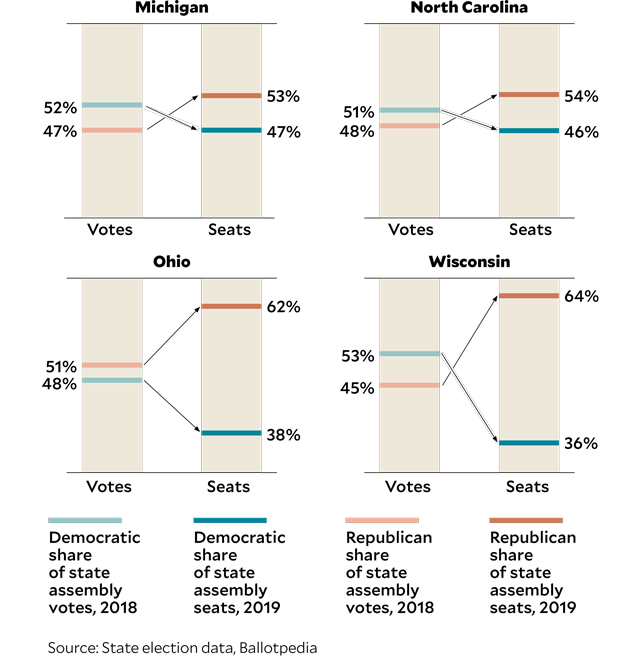

“This state is in some ways ground zero for gerrymandering,” Holder told two dozen BLOC canvassers who would knock on doors that afternoon for the progressive judge running in the race. “Last year they called it a blue wave, and yet you didn’t flip one congressional seat here in Wisconsin. That’s not because you didn’t work hard or people didn’t vote. It was because of gerrymandering.” Republicans had so effectively gerrymandered the state that even when Democrats won 53 percent of the statewide vote in 2018, they took only 36 percent of the seats in the state legislature.

Holder views gerrymandering, which manipulates district lines to benefit one party, as part of a broader struggle for voting rights, since it effectively diminishes the value of certain communities’ votes. “There is a direct connection between gerrymandering and voter suppression, not only here in Wisconsin but in places around the country,” Holder told me before his speech at the union hall. “It is not a coincidence that you see the greatest amount of voter suppression in those states where you see the greatest amount of gerrymandering.”

Holder visits volunteers phone-banking for Wisconsin Supreme Court candidate Lisa Neubauer in Madison in March.

Alyssa Schukar

For decades, Democrats successfully fought these twin efforts at disenfranchisement in the courts. As Obama’s attorney general, Holder led that charge, filing lawsuits against states like North Carolina and Texas that challenged Republican-backed laws curbing the right to vote. But this tactic was handed an enormous defeat in 2013, when the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in Shelby County v. Holder, ruling that states with a long history of discrimination no longer needed federal approval to change voting laws. Last week, the court struck another blow, declaring that federal courts couldn’t block partisan gerrymandering. Voting rights advocates face not only a hostile Trump administration but a growing number of federal benches controlled by conservatives. As the GOP’s war on voting has intensified, the traditional ways of protecting ballot access are no longer reliable.

So Holder is pursuing a new strategy, trying to elect down-ballot candidates who can deliver fairer maps and voting laws. The NDRC invested $350,000 in the Wisconsin Supreme Court race, hoping that a liberal majority on the seven-member court might strike down any egregious gerrymanders in the next round of redistricting in 2021. “I don’t think that 10 years or so ago, you would have a former attorney general campaigning for a state Supreme Court justice,” Holder told me. “This is a recognition on the part of the Democratic Party, on the part of progressives, that we need to focus on state and local elections to a much greater degree than we have in the past.”

But if Democrats are belatedly recognizing this need, few besides Holder are acting on it. He is playing a long game in a party driven by instant gratification and consumed by the mess in the White House. While the party’s presidential contenders are attracting big crowds, donors, and volunteers determined to defeat President Donald Trump in 2020, Holder is focused on 2021.

Eric Holder speaks to a Black Leaders Organizing Communities canvass meeting in Milwaukee on March 7.

Alyssa Schukar

Tayaveon Seals, 23, canvasses voters in North Milwaukee on behalf of the Black Leaders Organizing Communities organization. Earlier that day, Eric Holder spoke to the group, also known as BLOC.

Alyssa Schukar

The Constitution requires states to redraw their political districts every 10 years. In 2011, after routing Democrats in midterm elections the previous fall, Republicans took control of critical swing states including Wisconsin, drawing electoral maps that cemented their power. Now history is at risk of repeating itself. If Democrats don’t start devoting more attention and resources to state races, Holder warned the BLOC canvassers, 2021 could end up like 2011. The battle for control of state governments will determine the arc of American politics for the next decade, but it is already overshadowed by the 20-some Democrats running for president. Holder is fighting not just a well-funded Republican opposition but also his own party’s narrow focus on the presidency.

“I understand people are going to be legitimately focused on the presidential race, as we should be,” Holder said. “But it’s going to be my job to make sure we don’t lose sight of those other races that are going to be extremely important.”

Until recently, Holder’s strategy was a radical concept within the Democratic Party. Before the NDRC, there was no single group formulating a centralized strategy for gaining control of the redistricting process, as Republicans had done so successfully in 2010. That’s where Holder came in. Never before had a Democrat of his stature devoted so much attention to such a wonky issue.

“I famously said I’ve got to make redistricting sexy,” Holder recalled with a laugh as we sat in his Washington, DC, office at the law firm Covington & Burling, located in the glitzy new CityCenterDC complex. His corner office has views of the Washington Monument and busts of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson on the shelves. “My hope was—and I know President Obama’s hope was—that my being directly involved would give this effort a degree of attention that it might not otherwise have,” he said.

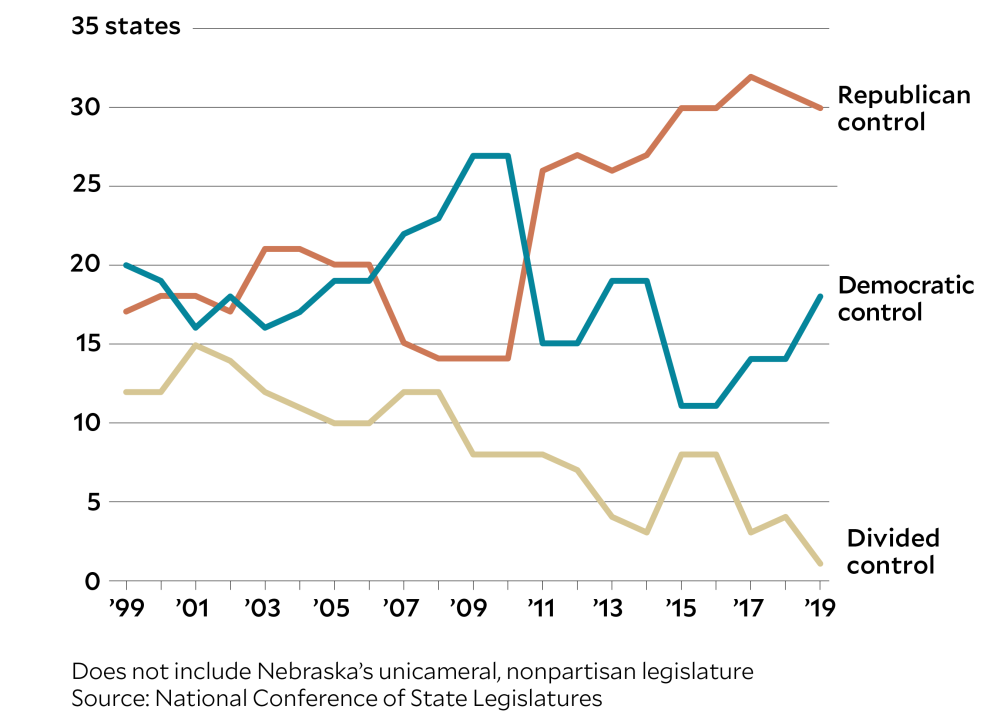

Democrats didn’t have a redistricting strategy because, for many years, they didn’t need one. They controlled a majority of state legislatures for most of the post–World War II era, drawing electoral maps in twice as many states as Republicans in the 1980s and 1990s. Democrats were sitting pretty heading into the 2010 elections after winning big in 2006 and 2008, controlling more than 60 percent of state legislative chambers.

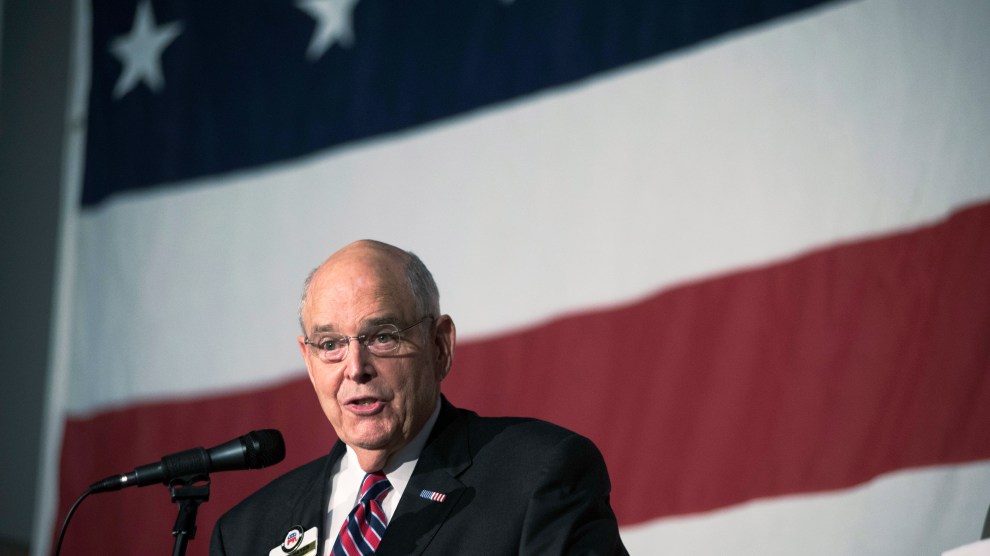

Then the GOP launched an aggressive bid to reclaim power at the state level, creating the Redistricting Majority Project (REDMAP) to target state legislative races and put Republicans in charge of redistricting efforts after the 2010 census. The effort was overseen by former Republican National Committee Chair Ed Gillespie and advised by strategists like Karl Rove. “He who controls redistricting can control Congress,” Rove wrote in the Wall Street Journal at the time.

Massively aided by the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision that allowed unlimited corporate political spending, REDMAP raised $30 million, including from oil, tobacco, and health insurance companies, three times as much as its Democratic counterpart. Republicans hoped to flip 25 to 30 House seats occupied by Democrats. They ended up winning 63, plus 20 new legislative chambers, giving them control of nearly every important swing state and the power to draw four times as many state legislative and House districts as Democrats. Nearly a decade later, Republicans still control every legislative chamber in heavily gerrymandered states like Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Tasha Gjesdahl of the University of Wisconsin-Madison chapter of NextGen America listens as Holder speaks to a packed room of young people near campus.

Alyssa Schukar

Democrats had no comparable strategy. And when the party controlled the White House and Congress after Obama’s 2008 victory, it paid little attention to the states. By the end of Obama’s second term, Democrats had lost nearly 1,000 state legislative seats. “This has been one of the big failures of our party,” said former Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, who led the Democratic National Committee from 2001 to 2005. “We have not paid attention to the importance of redistricting—haven’t put the time in historically.”

“One of the great deficiencies of the Obama operation during the eight years he was president,” said Obama’s former chief strategist, David Axelrod, “was that not enough attention was paid to legislative races.” The president, consumed by the financial crisis and the Obamacare fight, didn’t sustain a political operation that could combat the tea party wave and the GOP’s surgical targeting of state races. Now, Axelrod said, this deficiency is something Obama, a former state senator, “feels acutely, feels some responsibility for, and wants to help remedy.”

McAuliffe and House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi convened discussions during the 2016 Democratic National Convention about creating a group focused solely on redistricting. The initiative took on new urgency after Hillary Clinton lost the presidential race even as she won the popular vote, reinforcing the imperative that Democrats regain power at the state level. After the election, McAuliffe, Pelosi, and Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer visited the White House to get Obama’s blessing. “It was the president who said, ‘I’ll bring Eric in,’” McAuliffe recalled. Obama decided to make redistricting reform a central focus of his post-presidency and tapped Holder as his top lieutenant. Obama has hosted fundraisers for the effort, endorsed candidates in races the NDRC has targeted, and used his email list and social media profile to draw attention to the fight against gerrymandering. “In America, politicians shouldn’t pick their voters,” Obama said in a 2018 video promoting Holder’s group. “Voters are supposed to pick their politicians.”

For Holder, the cause was personal. “The right to vote,” he said when he launched the NDRC in 2017, was “a right that has been a part of my consciousness as long as I can remember.” As a 12-year-old in 1963, Holder sat in his basement in East Elmhurst, Queens, and watched on a black-and-white television as Vivian Malone became one of the first black students to integrate the University of Alabama. Twenty-six years later, he would marry her younger sister, Sharon, an obstetrician. Vivian went on to lead a group that registered black voters in the South and worked in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. She died in 2005, before Holder became the first black attorney general. “Her not being able to see her brother-in-law become attorney general of the United States is one of those really unfortunate things,” Holder told me in Wisconsin, his eyes welling up. “Even thinking about it now, I can get a little emotional.”

More votes, fewer seats

In some Republican controlled states, gerrymandering has made it all but impossible for Democrats to retake assemblies, even when they win a majority of the statewide vote.

Challenging the GOP’s redistricting edge required a multipronged approach: Holder’s group has filed or assisted a dozen lawsuits against gerrymandered maps, supported local candidates whose races had implications for redistricting, and backed state ballot measures to establish independent redistricting commissions. “He’s a uniting force between the different pieces of the Democratic ecosystem to get onto a shared strategy to rebuild Democratic power in the states,” said Jessica Post, executive director of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee and an NDRC board member. “Having a central electoral coordinating hub is really important.”

The Democrats’ gains in 2018 were impressive. Holder’s group raised $35 million—comparable to what REDMAP raised in 2010—helping Democrats flip about 300 state legislative seats, six legislative chambers, and seven governorships. In four states, including Wisconsin, Republicans lost sole control of state government, and with it their ability to single-handedly draw new districts. The NDRC targeted 230 state seats held by Republicans, focusing on suburban areas that were changing demographically; Democrats won 60 percent of them. Holder stumped for candidates in 24 states. “We gave financial support to races that otherwise might not have gotten financial support,” he said. “I campaigned in races that would not have gotten that kind of high-level attention.”

Party control of state legislatures

Though he hoped to elect more Democrats, Holder’s overriding goal was to make the redistricting process less skewed, putting him in conflict with some Democrats who wanted to maximize partisan gain. When New Jersey Democrats proposed giving legislative leaders more power over the drawing of district lines last year, Holder quickly denounced the plan. “I’m here for a fair process, not to gerrymander for Democrats,” he told me.

Holder, who has never run for elected office, is an unlikely public face for a major political campaign. He’s charismatic by the standards of a career lawyer, but no one would mistake him for Obama on the stump, though they do share a love of dad jokes. Still, Holder’s devotion to technocratic details can be an advantage when it comes to the nuances of redistricting. Holder said he viewed the fight against gerrymandering as a “jigsaw puzzle” and delighted in figuring out which pieces went where.

His efforts in Wisconsin began in March 2018, when the NDRC spent half a million dollars to elect Rebecca Dallet to the state Supreme Court, a huge amount for a state judicial race. Her victory brought Democrats one seat closer to ending the conservative majority on the court, which can rule on state voting laws. To increase African American turnout, Holder’s group funded BLOC, which knocked on 35,000 doors in Milwaukee in the spring of 2018 and helped achieve higher turnout in Dallet’s race in neighborhoods like Merrill Park than in a 2015 Supreme Court race.

Holder returned to Milwaukee last fall to campaign for Democratic gubernatorial candidate Tony Evers, for whom BLOC knocked on more than 173,000 doors in black neighborhoods that statewide political candidates usually bypassed. Evers defeated Gov. Scott Walker by just 30,000 votes, giving Democrats veto power over the state’s redistricting maps in 2021.

Holder also continued the efforts he’d begun as attorney general by taking Republicans to court for infringing on voting rights. When Walker refused to hold special elections for vacant state legislative seats in February 2018, Holder’s group sued and won. After the 2018 election, when Republicans cut back on early voting, Holder’s group sued and won again.

Walker criticized Holder’s work in Wisconsin on Twitter several months before the election; after losing, Walker became finance chair of a new group, the National Republican Redistricting Trust, focused on combating the NDRC. “My role is to counter Eric Holder’s efforts,” Walker tweeted. “He, with [t]he help of former President Obama, have raised some $200 million that they are using in court and on the campaign trail. Their goal is to secure Nancy Pelosi’s control as Speaker for a decade or more.” Walker dramatically overstated the amount raised by Holder’s group, but it was telling that the former Wisconsin governor—whose party Holder had been desperately trying to catch up with—now thought Holder was ahead of him.

The question now is whether Holder’s group can lock in and expand the gains made in 2018. Over the next year, the NDRC plans to almost triple its staff to 30, and the absorption of Obama’s vaunted Organizing for Action list will give Holder’s group access to hundreds of thousands of new volunteers to work on state races. “The single most important thing that could be done at the grassroots level over the next few years is to make sure the rules of the road are fair,” Obama said on a call with these volunteers in December 2018.

Eric Holder speaks to Black Leaders Organizing for Communities in Milwaukee.

Alyssa Schukar

Democrats are within six seats of flipping state legislative chambers in Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Minnesota, Arizona, and Michigan. “We’re much closer across the country than people think,” said the DLCC’s Post. But the GOP still controls 62 of 99 state legislative chambers nationwide and holds the governor’s mansion and both legislative bodies in 22 states, compared to 14 for Democrats. The bulk of the NDRC’s efforts will focus on five Republican-controlled gerrymandered states: Florida, Georgia, Ohio, Texas, and North Carolina. Gaining seats there will mean targeting districts in conservative exurbs where Democrats came up short in 2018. Mark Gersh, a Democratic redistricting expert working with Holder’s group, said the team is “trying to figure out whether Trump’s plummeting popularity and behavior might enable us to go beyond the parts we know we can win, because there’s not enough of them. We won all the low-hanging fruit last time.”

There’s momentum, though. The once-wonky issue of voting rights has become a rallying cry for Democrats. In 2018, voters in five states approved ballot initiatives that curbed gerrymandering. When Democrats took control of the House, their first piece of legislation was a sweeping reform bill that called for independent redistricting commissions to draw all House districts. (The proposal died in the Senate after Republican leader Mitch McConnell refused to hold a vote on it.) Schumer said in March that the fight for voting rights should be one of the Democrats’ top three issues, alongside climate change and income inequality.

Voting rights are “part of a basket of issues that are motivating to people who feel like the character of our democracy is being threatened and that democracy itself is being manipulated,” said Axelrod. But Democrats are still in jeopardy of ignoring the state and local races that will determine the country’s voting maps. “Our concern is there’s wall-to-wall coverage of Trump scandals, wall-to-wall coverage of crowd size and presidential announcements, and our job is to continue to make sure people know that the next decade of democracy is on the line in 2020,” said Post.

Democratic strategists working on down-ballot races say the presidential campaign is siphoning away resources. “It’s harder to recruit people [to run], it’s harder to get attention to these races, it’s harder to raise money for them,” said Amanda Litman, executive director of Run for Something, which recruits progressive candidates for local offices. “Quite a few of the donors we work really closely with have been hesitant to reengage, either because they’re tapped out from 2018 or they’re waiting for the presidential race to shake out.”

Litman’s group is coordinating with the NDRC to recruit state legislative candidates to run in every district in the 12 states Holder is targeting in 2020, but she said reaching Run for Something’s $3 million fundraising goal this year “is like pulling teeth.” That’s small change for presidential candidates like Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden, who each raised about twice that sum on the first day of their campaigns, but it could make the difference in flipping multiple state legislative chambers, Litman said.

More money might have changed the outcome of the Wisconsin Supreme Court race. Lisa Neubauer, the progressive judge backed by Holder, was favored to win. But in the final week of the race, the Republican State Leadership Committee, the same group that bankrolled the GOP’s takeover of the state legislature in 2010, launched a $1.3 million ad campaign for Neubauer’s opponent, Brian Hagedorn, an ultraconservative judge and former chief counsel to Walker. Meanwhile, Republicans made Holder a talking point—a Facebook ad from Hagedorn admonished, “We can’t let Eric Holder reshape Wisconsin’s Supreme Court”—and Neubauer called on Holder and other outside funders to stay out of the race. Turnout surged in conservative, rural parts of the state, and Hagedorn won by about 6,000 votes, cementing a right-wing majority on the court through at least 2023.

The day after the election, Holder spoke at the annual convention of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network. A dozen Democratic presidential candidates were there, and none had campaigned for Neubauer. “It seems I’m the only one here who isn’t running for president in 2020,” Holder joked. He’d flirted with his own long-shot presidential bid but decided against it, in part to remain focused on redistricting. He said “we should have won” the Supreme Court race and worried that the presidential contenders weren’t talking enough about the down-ballot contests that Democrats need to win to reverse the GOP’s redistricting edge.

Holder was dismayed that he’d been the only prominent Democrat to campaign for Neubauer. “I’m still a little bit wound up about this one,” he told me two weeks after the election. “This should be a wake-up call for us. I felt a little lonely out there in Wisconsin.”