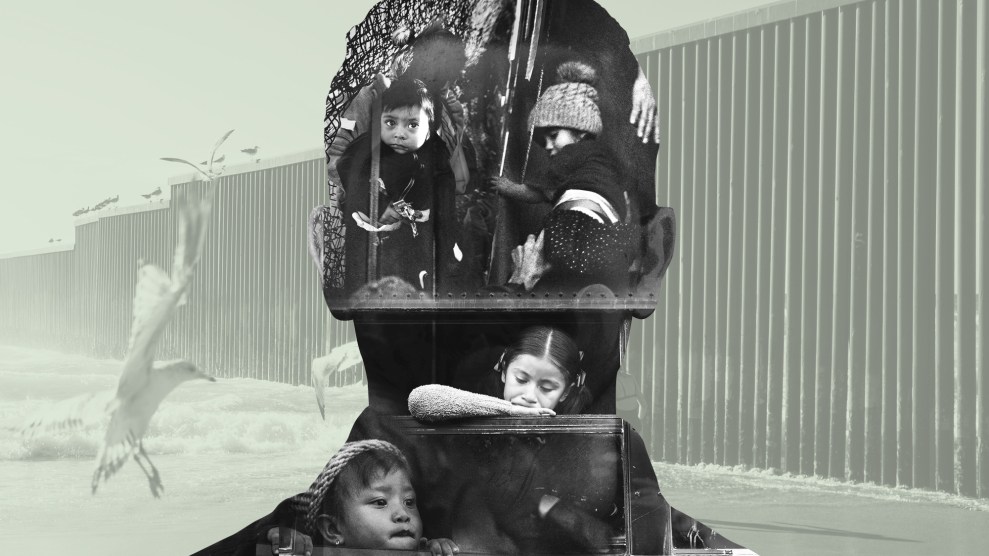

Immigrants wait to be interviewed by Border Patrol agents in McAllen, Texas, in early July.John Moore/Getty Images

The Trump administration is about to make it much more difficult for migrants to seek asylum in the United States, announcing a new policy Monday that would drastically change asylum policies as we know them.

The new rule, set to go into effect Tuesday, would force migrants from anywhere outside of Mexico or Canada to seek asylum in a “third country”—neither the country they’re fleeing nor the United States, but rather any country they passed through on their journey to the US border. It would also allow US immigration officials at the border to quickly deny the cases of asylum seekers who don’t pass an initial interview and deport them to their country of origin.

“Until Congress can act,” said acting Homeland Security Secretary Kevin McAleenan in a statement, “this interim rule will help reduce a major ‘pull’ factor driving irregular migration to the United States and enable DHS and [the Department of Justice] to more quickly and efficiently process cases originating from the southern border, leading to fewer individuals transiting through Mexico on a dangerous journey.”

This is the latest in a series of policy changes in the last two years to deter migration to the United States, particularly from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The White House already limited the number of people who can legally ask for asylum at a port of entry on any given day, forcing thousands to wait in Mexican border towns. Once migrants make their case for protection in the United States, the so-called “Remain in Mexico” policy forces them back to Mexico to wait for their day in immigration court. Migrant aid organizations in Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez, and other border cities have been critical of these policies, saying they put vulnerable migrants at risk.

Immigrant rights groups are already lining up against the newest regulation; on Monday, the ACLU said it would sue the government over the “patently unlawful” rule. But according to Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, it might be difficult for these legal challenges to quickly stop the regulation from going into effect.

I interviewed Pierce on Monday afternoon, and we discussed the legality of the policy, the most concerning parts of it, and what it could mean for other countries involved. Our discussion has been edited for content and clarity.

What is the most problematic thing you see with this new decision by the Trump administration?

This new regulation effectively ends asylum at our southern border. Even more problematic, individuals who would qualify for asylum in the United States will be deported back to the countries from which they fled.

How will that work?

If they determine that a migrant applying for asylum at the southern border is subject to this new regulation, then they’ll subject the migrant to a higher standard interview, called a reasonable-fear interview.

If, in the unlikely event the migrant is able to get through that reasonable-fear interview, they can still go into immigration court to try to stay inside the United States, but they’ll be applying for “withholding of removal”: They won’t get to apply for asylum, and it’s not only more difficult to get, but it also gives you fewer benefits. You don’t get status in the United States; you don’t get the opportunity to apply for a green card or citizenship. It’s really just a temporary promise not to deport you, and it gives you the ability to apply for temporary work authorization.

So you’re saying that when someone asks for asylum at a port of entry on Tuesday—say, someone who traveled from Honduras—and they didn’t apply for asylum in Guatemala or Mexico, then they go down this path that you just described?

Exactly. That’s right.

And there’s a real possibility that they will be deported right away, because what they’ll be subject to is much more difficult. So for instance, if they’re not able to get through that initial reasonable-fear interview, then they’ll be subject to what’s called “expedited removal”—and they’ll be deported within a few days, at most, back to their home country.

This is placing a huge burden on asylum seekers—and a huge burden on the asylum systems of these countries south of our border. Mexico is already hugely overwhelmed by the number of asylum applications that they’ve received. The idea that they’re going to receive a bunch more because of this new regulation is going to be very difficult for the country and their already very frazzled asylum system…

Nothing in this regulation requires you to apply in a safe country. It just requires you to apply in a country to which you’ve transited.

How is this different from the safe third country agreements that we’ve been hearing so much about in recent days?

Under a safe third country agreement, we would typically deport a migrant to that safe third country. For example, if you tried to enter our northern border and you hadn’t yet applied for asylum in Canada, we were deport you back to Canada. But in this case we’re not going to be deporting migrants back to Mexico. Instead we’ll be deporting them back to their home country.

Also, family members need to individually qualify for withholding of removal, where before, if one member of a family qualified for asylum, the others would just get kind of an automatic derivative asylum status. But withholding of removal forces each individual family member to apply.

Even a child?

Yeah.

So a mom and her two kids could go through this process and the mom has a credible fear interview she passes, but the kids don’t.

That is a possibility.

What legal challenges does this new policy face?

It’s probably going to be somewhat similar to the litigation we saw around the administration’s asylum ban. Not that long ago, the administration tried to make anyone who crossed the southern border illegally (between ports of entry) ineligible to apply for asylum. That went into effect for about 10 days before it was enjoined by federal courts.

That provision used a similar part of a law to this new third country transit bar. In that initial asylum ban case the judge found that the administration had gone too far, that they had countered the express will of Congress when they decided to bar individuals who had crossed the border illegally. Again, a judge will be looking at whether or not the administration has gone too far or is this within their abilities and which groups are looking to sue.

Do you see anything in this document that’s that jumps out as legally questionable or illegal?

I think that there are things that this regulation could be enjoined on. I’m just not sure advocates are going to have as strong an argument as they’ve had in challenging some of the administration’s past actions on immigration. I would not be surprised if it got enjoined. But I also won’t be surprised if it doesn’t get enjoined.

So it’ll could be a little harder to press pause on this than it has been with other Trump administration policies on immigration?

Yeah, that’s exactly what I’m trying to say.

What will this actually look like at the border? Will asylum seekers simply be denied quicker than before?

They will be denied more quickly, and then, once they’re denied, we’ll be able to deport them—which isn’t something that the administration can do right now. The vast majority of asylum seekers at our southern border are permitted to enter the United States and wait here while their asylum claims are being adjudicated. So this will be really resource intensive for the Department of Homeland Security, and it will likely drastically increase the number of deportations they’re conducting.

But it is also a possibility under this regulation that we’ll have to house people for less time at the southern border. Also, if the administration successfully implements this, I think we’ll see a decrease in how many people are applying for asylum at the southern border. Because if people know that their chances are so drastically reduced, they’re going to be less likely to journey into the US border and try to apply for asylum.

Does it concern you at all that these decisions are going to be made so quickly at the border without going in front of immigration judges and having a little more time to prepare?

Yeah, absolutely. I think someone who was recently apprehended at our southern border who hasn’t yet spoken to an attorney or any other resources about this application process is not well equipped to be subject to the reasonable fear standard.

It’s worth hammering the fact that you could have migrants who would qualify for asylum in the United States, and under this new regulatory structure they’ll be deported back to their home country because they don’t qualify for it—unless there’s a benefit of withholding of removal. So normally we would welcome these people in the United States as a way to relieve them of the persecution they face in their home country. Instead, we would be quickly deporting them back to that persecution.