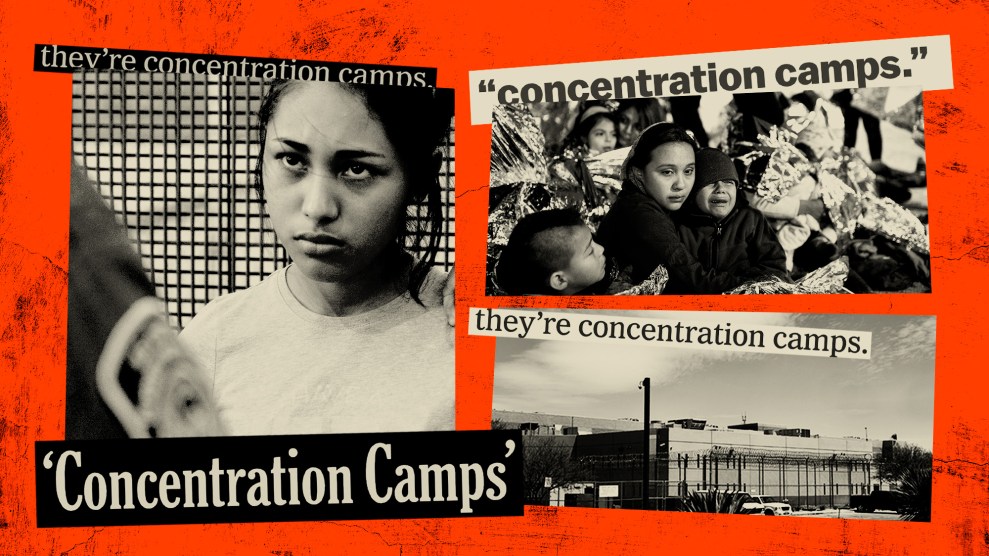

Mother Jones; Paul Ratje/AFP/Getty; Carolyn Van Houten/The Washington Post/Getty; Richard Vogel/AP

Most of the historians who study these things seem to be calling them concentration camps. I don’t know what kind of sentence is supposed to come after that. The president keeps threatening to go city by city rounding up millions of people, and we’re left to hope it’s just another one of his lies, like when he jokes about refusing to leave office even if he loses the election.

If someone knows exactly what to do right now I haven’t met them yet, and I’ve been asking around. We don’t have the capacity to protect each other from the state, which means we can’t protect ourselves either. Aside from a legal speed bump here and there we’re at the discretion of a violent, addled demagogue and the henchmen craven enough to have stuck by him this long. Incompetence and lack of imagination are our checks and balances.

I don’t believe that populations are necessarily helpless before their governments in the 21st century—people still stand up and fight back around the world, from Sudan to Haiti to Hong Kong—but as an American it sure feels that way sometimes. Despite our pervasive sense of crisis, the relationship between the people and the state has never been so calm. The uprisings that flared under President Obama against wealth inequality, police violence, and pipeline construction have been quelled. Every once in a while the president’s liberal detractors gather to call for investigation and impeachment, but the crowds skew elderly, and there have been no conflicts with the security forces (whose unions strongly support the president). The radical left has found itself running just to keep pace with the overtly fascist right.

In 2016 the Boston Globe’s op-ed section produced a “satirical” front page imagining what headlines would look like under Trump. They got a lot right: “DEPORTATIONS TO BEGIN,” a headline read, with a sidebar on a looming trade war. Friday’s Miami Herald headline opens, “Deportation crackdown expected to start.” But when the Globe’s editors envisioned a Trump presidency, they figured there would be heavy pushback. “Riots continue,” the subhed says, and the article features round-the-clock protests blocking transportation infrastructure and filling the nation’s cities with teargas. There have been no riots, hardly even any serious protest. We can all see the tyranny; where is the resistance?

Since Trump’s ascension “The Resistance” has become a brand name, a content category, a group identity for the older suburban liberals who have boosted MSNBC to record audience numbers. Together The Resistance pores over every detail of the president’s internal affairs investigation, waiting for the day the cops finally throw the cuffs on Trump and his whole wicked cabal. A sizable portion of the audience is fully in earnest and is probably responding to the only call that’s been addressed to them, but The Resistance is no resistance movement.

Resistance is a political mode of engagement that is outside the liberal-democratic model envisioned in the text of the American Constitution. At a Berlin conference about Vietnam in 1968, Dale A. Smith, a delegate from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, spoke stirringly of the difference between protest and resistance. Protest is when you say you don’t like something, he said. Resistance is making sure no one likes it. Protest is when you say, I will not tolerate what they do. Resistance is preventing them from doing it. Protest means to detest the inhumanity of others. Resistance means to suppress their inhumanity to let humanity triumph.

Resistance looks like London’s Anti Raids Network. Formed in 2012, the network is a leaderless, decentralized coalition of groups that struggle against deportation in various ways: distributing information, organizing shops with immigrant workers, and engaging in forms of direct action. Some crews track and follow the “snatch vans,” named for their role in the abduction of undocumented immigrants. When the authorities prepare for a raid, the network alerts people Paul Revere style, blocks the van, and hinders the officers however they have to. Less lobbying officials, more lobbing objects. The work requires the sort of consequentialist thinking that American liberals don’t eagerly embrace. These activists figure that any disruption to the deportation machinery is an obvious net positive when it comes to pain and suffering, even if an anti-raids crew were to occasionally, say, brain a cop with an egg. Members of the network have agreed not to condemn any actions taken against immigration raids.

In the US, immigrant defense work is less crafty. The church-led movement operates with an understanding that allows it to provide sanctuary for some undocumented people while pursuing legal remedies, as well as moral support when those remedies fail. The Resistance holds occasional days of action and even managed a national mobilization against Trump’s “Muslim ban,” but administration lawyers outlasted and outmaneuvered the protests, securing a 5-4 vote from the Supreme Court in favor of the ban. The radical left-wing movement’s plan to “Occupy ICE” was a mix of tactics and strategies—part street protest, part lockdown, part encampment—that (with the exception of Portland and Los Angeles, where local officials lent their support) failed to materially obstruct the agency’s work and resulted in numerous arrests. There have been lots of individual skirmishes between immigrant communities and ICE, but nothing organized, protracted, and fearless.

A group of committed Americans could use the London model to disrupt the deportation industry wherever they live. I don’t think there’s any lack of enthusiasm for this kind of action, and people with different skill sets could contribute in lots of different ways—from data scientists figuring out where to patrol, to musicians rigging mobile sound systems, to bike messengers racing vans. Are ICE agents more devoted to doing their jobs than we are to stopping them? Are they more courageous? Are their security professionals better than our hackers, our catfishers? I have no doubt that we the set of Americans who find ICE intolerable have the capacity to frustrate its operations, and in ways that no individual can imagine on his or her own. How many people and how much money would it take to set up a functional anti-raids cell? Those questions have answers.

But meaningful resistance comes with serious risk. A confederation devoted to disrupting the Department of Homeland Security and halting the enforcement of immigration law at scale is guaranteed to be treated like a terrorist group, even though its purpose and methods would have nothing to do with terrorism. It’s the conceptual violence of anti-raids action more than any threat to the safety of its personnel that DHS would find unacceptable: both the general idea of people organizing to resist the law and the specific resistance to the government’s ethnic cleansing program. People who involved themselves in this kind of activity could be risking significant prison time. And that’s if a government that many of us recognize as well within the fascist tradition limits itself to standard practices for dealing with political prisoners, which is not something that fascists are known for.

One reason I think we’ve been arguing about the name of the camps is that life in the shadow of concentration camps is not supposed to be worth living. “Never again” doesn’t mean “Don’t commit genocide” or even “Oppose ethnic cleansing”; the phrase implies a permanent obligation to resist in the Dale Smith sense—stop the camps—or risk being the equivalent of all those Good Germans. The presence of concentration camps should be intolerable, and yet here we are, tolerating it. Either they aren’t camps or we aren’t who we said we were. There has got to be a better way to reduce our cognitive dissonance than playing with definitions.

A lot of American regions, cities, and towns have rapid response networks that, in the event of an ICE raid, give immigrants a number to call for help. Volunteers provide information, witness, and moral support. As near as I can tell there’s only one American network that publicly employs a full diversity of tactics, including confrontation—Los Angeles’ Koreatown Popular Assembly. In January of last year they blocked ICE agents from returning to a 7-Eleven as part of a national wave of raids on the convenience store chain. A month later the group blocked an immigration van outside of a prison downtown in retaliation for immigration raids. That’s a model, and a start. Leftist writer Arun Gupta’s simple call for a march on the camps—which are intentionally located far from population centers—has been resonant as well. A meaningful conflict with the state requires tactics and strategies that almost no one is used to in America.

The crackdown on immigrants isn’t new or even exclusive to Trump, but that doesn’t mean we can’t recognize today’s particular danger. To engage in resistance probably means becoming a target for the federal government’s repressive apparatus, but at least that might put us in good company. Better to be with the abused than looking for an excuse in euphemisms. Hell, better to be dead than a Good American. When those are the only options left, there can be no choice.

Malcolm Harris is the author of Kids These Days and the forthcoming Shit Is Fucked Up and Bullshit.