Mother Jones illustration; Getty; Zuma

Mayor Pete Buttigieg was keeping a low profile. It was last spring, and he was in the middle of deliberating what he would later call “one of the hardest decisions” he’s had to make during his tenure in South Bend, Indiana. An abortion clinic—which was hoping to offer service to a city without a single provider—was trying to open. A crisis pregnancy center (CPC)—a pro-life facility that counsels women against getting abortions—was trying to open up directly next door.

To the relief of the clinic, Buttigieg eventually barred the CPC from its desired location. But he did so without ever taking a stand on the issue at the heart of the rezoning debate: reproductive rights. He relied on arguments of community peace while equating the two diametrically opposed groups as “good residents who seek to support women.” He even offered to “help” the anti-abortion organization open elsewhere, despite evidence that the vast majority of crisis pregnancy centers provide false or misleading information to the women they claim to serve.

Buttigieg has spent the past several months campaigning as a pro-choice candidate for president, but this episode in his hometown underscores a broader pattern in which he avoids talking proactively about the issue of abortion rights and offers platitudes in place of specific policy. While the compromise in this particular incident was arguably politically prudent in conservative Indiana and heavily Catholic South Bend, it’s important to consider it in a larger context.

When the Republican-controlled Alabama legislature, for instance, passed a draconian law effectively outlawing abortion last month, the response from several top Democratic presidential contenders was swift and furious. Immediately, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand called the law a “war on women” and rallied people to “fight like hell”; Sen. Kamala Harris made allusions to The Handmaid’s Tale in an email sent to raise funds for abortion rights groups rather than her campaign; and Sen. Elizabeth Warren evoked memories of “back-alley butchers” before dropping a robust reproductive rights plan. Sen. Bernie Sanders called on Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey to veto the “blatantly unconstitutional” and “cruel” bill heading toward her desk. Sen. Cory Booker vowed to “fight in solidarity with women,” and when Ivey signed the bill into law the following day, he pledged to support federal legislation codifying Roe v. Wade, legalizing abortion nationwide regardless of the Supreme Court’s position.

Buttigieg, meanwhile, waited until the morning after the Alabama Senate passed the ban to tweet that the state was “ignoring science, criminalizing abortion, and punishing women,” and that “the government’s role should be to make sure all women have access to comprehensive affordable care, and that includes safe and legal abortion.” There was no policy prescription attached, no rousing call to action. In comparison, his was one of the weaker responses. (Former Vice President Joe Biden also waited overnight to respond and offered a somewhat lackluster reaction.)

Buttigieg typically falls back on the familiar arguments that it’s simply not his role as a male politician to make this choice for a woman, and that abortion is just an issue of freedom. These are not points that abortion advocates would argue with, but they may also think they’re no longer enough—particularly at this moment, when abortion rights are under serious attack. As other candidates come out forcefully and specifically in defense of abortion and propose proactive plans to protect women’s rights, Buttigieg may fail to satisfy Democratic primary voters, who increasingly view reproductive rights as a priority.

“I’ve heard less from him on this issue in a proactive way,” says Destiny Lopez, co-director of All* Above All, a reproductive rights advocacy group, and former director of Latino engagement for Planned Parenthood Federation of America. “We’re looking for candidates who can both acknowledge the harms that are currently being done by existing policies…but also have a vision for what they plan to do on day one in office to stem the tide of bans and create a future where a person can access abortion regardless of where they live and how much money they make.”

Indiana’s lawmakers have been notoriously hostile toward reproductive rights; when compared to his fellow Hoosiers, Buttigieg is actually much further to the left on abortion rights. “Statewide, Democrats do not win their races if they are pro-choice,” says Sue Ellen Braunlin, co-president of the Indiana Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice. Governor-turned-Vice-President Mike Pence passed a number of restrictions during his tenure, including one sweeping law that mandated advanced informed consent, limits on fetal tissue disposal, and the burial or cremation of aborted fetuses. (Parts of that law have been struck down by lower courts, but in May the US Supreme Court upheld the fetal remains requirement.)

The impacts have rippled statewide: In 2011, the year before Pence was elected governor, there were 12 abortion providers in the state. Today, there are only six, three of which are in Indianapolis.

In part due to these restrictions, there is little access to abortion services in or near South Bend—a left-leaning city with a notable Catholic influence, given that the region’s biggest employer is the University of Notre Dame (currently the defendant in a lawsuit brought by students for restricting access to contraceptives). “South Bend is a curious place—it’s a Democratic stronghold with a strong labor but also Catholic presence,” says Braunlin. “And there’s terrible access to abortion.” In his memoir, Shortest Way Home, Buttigieg recalls that at his Catholic high school, there was a “monument to aborted fetuses on school grounds [that] reminded us all that pro-life politics was an article of faith.”

The only clinic in the city stopped offering abortion services in 2015 and closed permanently in 2016 after being open for 30 years.

At that point, the operating abortion provider closest to South Bend was in Michigan, about 45 minutes away by car; within Indiana, it was over an hour away by car and virtually inaccessible by public transportation. In an effort to improve residents’ reproductive health options, local pro-choice groups invited Whole Woman’s Health Alliance, a nonprofit chain of abortion clinics, to open a location in South Bend. “I knew it would be a clinic that would be very difficult to keep the doors open,” says Amy Hagstrom Miller, founder and CEO of Whole Woman’s Health Alliance. The nonprofit spent the next couple years fundraising and seeking grants to build a cushion of support in case it encountered state-level interference.

The organization eventually found, built out, and furnished a space on a grassy corner along a three-lane thoroughfare close to the airport, with a residence on one side and a gas station on the other.

Before it could open, the clinic needed to apply for a license from the Indiana State Department of Health, which it did in fall 2017. In January 2018, the department rejected the application, saying Whole Woman’s Health failed to prove its “reputable and responsible character” and didn’t disclose enough information about its clinics. After months of appeals, reversals, and what Hagstrom Miller says felt like a run-around from the health department, the nonprofit asked a federal court “for emergency relief” so the clinic could open.

In the meantime, a group called the Women’s Care Center decided it wanted to open a facility in the lot next door to the pending abortion clinic. Women’s Care Center runs what are commonly called “crisis pregnancy centers” (CPCs)—facilities that offer prenatal services but are known for disseminating false medical information and using misleading tactics, offering free ultrasounds and pregnancy tests to draw in women seeking abortions and then counsel them against the procedure. Women’s Care Center already operated 16 sites in the state, including three other South Bend locations. A donor’s $500,000 contribution to the planned CPC hinged on setting up next door to the abortion provider. Getting as close to abortion clinics as possible is common practice for the group; 22 of Women’s Care Center facilities across the country are next to or across the street from abortion providers. These operations often draw unwanted attention to abortion providers from anti-choice advocates and leave some women who come to their sites feeling tricked or pressured. (The Women’s Care Center declined to respond to questions from Mother Jones.)

There was one hiccup with the Women’s Care Center plan: The property it wanted was zoned for residential use. In April 2018, the organization petitioned the nine-member city council, called the South Bend Common Council, to rezone the building. The council would make a decision, but the last word on the rezoning would rest in the veto power of Mayor Pete Buttigieg.

The first public hearing on the zoning issue lasted more than three hours, with people spilling out of the meeting room into the lobby. Advocates on both sides testified and told personal, sometimes emotional, stories. One woman shared her experience of getting “aggressive” treatment when she accidentally ended up at one of the Women’s Care Center offices. She had to go through “mandatory counseling” and “intrusive questions” about her choice to have an abortion, and she started receiving mailings about parenting. “The intimidating mass of people here tonight feels all too familiar,” she said at the hearing. Indeed, the crowd was dominated by supporters of the Women’s Care Center donning pink, some of whom spoke about the many ways the CPC chain has helped women in the area. “The fact that [the debate] was a rezoning issue got lost in the larger context,” says John Voorde, an at-large common council member.

The council members delayed their vote for more time to consider the issues and to see if the two facilities could reach a compromise. When they finally made the decision two weeks later on April 23, hundreds of people, especially abortion opponents, again dressed in pink, showed up at the hearing—so many that the fire department had to turn some away. The council voted 5-4 to rezone the property and let the crisis pregnancy center open next door to the abortion clinic.

It was then up to Buttigieg. The few days following the council’s decision were filled with calls and meetings and press inquiries as the mayor deliberated. “I’ve heard from hundreds of people on both sides of the issue with very passionate views,” Buttigieg said later at a press conference. (The Buttigieg presidential campaign declined requests to comment from Mother Jones.)

Pro Choice South Bend had collected hundreds of online signatures against the rezoning, and following the council’s decision, the group re-opened its petition to pressure Buttigieg to use his veto power. These actions and others, including a letter writing campaign by local abortion rights advocates, prompted the mayor’s office to reach out to Whole Woman’s Health Alliance, according to Sharon Lau, Midwest advocacy director for the nonprofit.

Hagstrom Miller says her group talked with the mayor about its concerns for patients—that they would be screamed at and targeted while entering their facility or dissuaded and lied to at the CPC. Whole Woman’s Health had received complaints from patients about Women’s Care Centers operating near its abortion clinics in Baltimore, Maryland, and Peoria, Illinois—information it shared with Buttigieg. After a phone call with the mayor’s office, the organization sent a long follow-up letter filled with data and stories of clinics’ damaging experiences with crisis pregnancy centers. “We had a lot of documentation from the Peoria staff from upset patients who had gone there by mistake,” Lau says. “It really contradicted what the Women’s Care Center said was their model.”

The mayor and his staff agreed, Hagstrom Miller says, that residents shouldn’t be harassed or picketed, and he seemed to sincerely take those risks into consideration.

Buttigieg said he raised those concerns in negotiations with the Women’s Care Center. The crisis pregnancy center insisted it had never had such issues near abortion facilities before and quickly posted language on its website clarifying that it doesn’t perform abortions and offered promises to city officials to prohibit abortion clinic protesters on its property. (Still, over the course of the citywide debate, many speakers at the council hearings and even the Women’s Care Center’s executive director noted that they could not prevent people from protesting against the clinic if they weren’t on the center’s property.)

For several days, Buttigieg was largely quiet in public. Then, four days after the Common Council’s vote, Buttigieg vetoed its ruling. In a letter to council members explaining his decision, Buttigieg seemed persuaded by data the abortion clinic had presented showing significantly higher rates of threats, harassment, and violence for clinics near crisis pregnancy centers.

Notably, Buttigieg took pains not to pass judgement on the merits of crisis pregnancy centers themselves. “I have very high regard for the representatives and volunteers of the Women’s Care Center whom I have met and heard from,” he wrote in a letter to city council members. “I believe that both they, and the Whole Women’s [sic] Health Alliance, are good residents who seek to support women by providing services consistent with their values.”

And at a press conference announcing his veto, Buttigieg said, “Issues on the morality or the legality of abortion are dramatically beyond my pay grade as mayor. For us this is a neighborhood issue, and it’s a zoning issue.” It was “one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made in this job,” he added.

Still, the veto wasn’t the end of the road for a new Women’s Care Center. At the veto presser, Buttigieg explained: “What we’re going to have now is hopefully an opportunity for Women’s Care Center to decide if they want to continue expanding some of the services that they provide especially to new and expecting mothers,” noting that there were plenty of other viable and nearby possible locations. And in a TV interview in mid-May, he said, “We continue to stand ready to work with them on finding another site….There are so many other locations in that neighborhood that if they would like to expand to a seventh location in our area.”

“We’re happy to help,” he concluded.

By the beginning of June, the facility found a new space—right across the road from the still-stalled abortion clinic. Buttigieg then told local press, “From the beginning the big question was, if there’s some way, any way that the Women’s Care Center could meet their mission from a different site, one that was less controversial and didn’t have the same zoning problems. It sounds like they’ve been able to identify such a site, and that’s certainly something that we support.”

For the clinic’s part, Hagstrom Miller and Lau say they were happy with Buttigieg’s openness to their concerns and, of course, his veto. In Lau’s view, with the Women’s Care Center across the street instead of next door, “it makes it less directly confrontational.” Still, “it’s certainly not ideal,” she says, pointing to the fact that there have already been anti-abortion protesters at the pregnancy center and that women may still get duped into going to the wrong facility. “Their goal is still going to be confuse women.”

Hagstrom Miller adds, “It was fantastic to have him veto it…but also, I think he knew that they could go across the street. Basically his statement was about rezoning, right? It wasn’t about pro-choice advocacy.”

Only this month, more than a year and a half after its initial license application, did the Whole Woman’s Health clinic get the okay to open in South Bend. A federal judge issued a preliminary injunction to allow the facility to operate until a lawsuit from Whole Woman’s Health Alliance against Indiana is resolved. (That trial is set for August 2020.) “I’m definitely standing with those who want to provide support for those women,” Buttigieg said following the court’s decision.

Despite this victory for the clinic, Whole Woman’s Health, which is currently staffing up and plans to open within a few weeks, has a long road ahead. The judge’s injunction isn’t permanent, and Indiana Attorney General Curtis Hill has already appealed the decision. (Buttigieg called Hill’s actions “politically motivated.”) In the meantime, protesters have been intermittently showing up at the still-closed clinic, rallying outside and vowing to sustain the effort when it opens for business. Whole Woman’s Health is talking with local law enforcement and gathering volunteers to act as clinic escorts in anticipation of ongoing harassment.

While, as mayor, Buttigieg did not have the authority to bar the crisis pregnancy center from opening, it’s worth revisiting his role in the episode, the help he offered the center in finding a new location, and the current options for women needing reproductive care in South Bend, to understand how a President Buttigieg might approach reproductive justice.

“In South Bend, it’s kind of like a microcosm of the country which is how small towns are,” Hagstrom Miller says. “On many levels, a lot of the issues we’re dealing with in the country show up at the local level in communities, and South Bend is no different…and I think these local battles are really important.”

Buttigieg has a reproductive rights section on his campaign website, though it is light on details. He supports repealing the Hyde Amendment, which bars federal funds from paying for abortions, something even many Democrats haven’t called for, though that’s changing; Biden, for instance, recently confirmed he in fact still supports Hyde, before he quickly reversed course following a backlash. But beyond that, Buttigieg has shied away from other specific or proactive policy prescriptions to protect or promote reproductive rights. Buttigieg models his stance on the commonly invoked female mantra of “my body, my choice”—men should not decide what women can or can’t do with their bodies—or that the issue is as simple as “American freedom.”

In February, Morning Joe host Joe Scarborough asked Buttigieg whether he supports legislation allowing late-term abortions in certain cases, like that passed in New York and proposed in Virginia. Buttigieg replied that “when a woman is in that situation…extremely difficult, painful, often medically serious situations where life or health of the mother is at stake, the involvement of a male government official like me is not helping.” Scarborough then asked if states should be able to ban abortions after 20 weeks (though the commonly agreed upon standard from Roe is 24 weeks). “That sounds like a constitutional question. I’m not a legal scholar,” Buttigieg deflected. “What I know is that these questions ought to be resolved by women in consultation with their doctors, not by the intervention of male politicians.”

On Meet the Press in April, Buttigieg put it this way when asked whether he believes there’s any role for government in abortion and how he squares the issue given his religious and red state roots:

“This is a question that is almost unknowable. This is a moral question that is not going to be settled by science. And so, the best way for it to be settled in practice is by the person who actually faces the choice. When a woman is facing this decision in her life, I think in terms of somebody besides her who can most be useful in that, the answer to that would be a doctor, not a male government official imposing his interpretation of his religion.”

Hagstrom Miller argues that even if unintentional, the implication here is that men have no stake or responsibility when it comes to abortion. “When we frame it as a woman’s issue, it’s damaging because then it gives people the opportunity to write it off, and to say, ‘Oh, it doesn’t apply to the majority of people,'” she says. “I think there are ways that men can talk about abortion, respectfully, with dignity and empathy. And I think it’s something that needs to happen in order for people’s ideas about abortion to shift in this country.”

“Surely, he can be more precise than that,” she adds. “To say, ‘Well, I can’t speak to that, because I’m a man,’ that’s crazy…I think it’s a cop out.”

Lopez, from All* Above All, echoes this sentiment: “We’ve seen some of the other male candidates actually say quite the opposite, which is, ‘I’m a man, and I have a role to play here in amplifying the work that women are doing,’ and calling out and amplifying this as an important issue that men need to vote the right way on,” she says. “There is a proactive role that the male candidate candidate should play”

Moving forward, it will be increasingly hard for Buttigieg to get by on this type of language alone. Several of his presidential competitors, like Sens. Gillibrand, Harris, and Warren, are being aggressive on this front, releasing plans to stop abortion laws from going into effect unless the federal government agrees to comply with Roe v. Wade or to repeal Trump’s gag rule that effectively strips Planned Parenthood of federal funding. They’ve also agreed to only pick Supreme Court judges who agree Roe is settled law, something Buttigieg hedged on recently, saying instead he’d look for judges that “had the same philosophy [as him] around freedom.”

“We’re seeing a field of candidates that have been quite vocal on this issue…because I think they’re stepping up to the fact that we’re in the midst of a national conversation on it in a way that we haven’t been as a result of all these abortion bans,” Lopez says. She says she’d like to see Buttigieg present a specific policy vision on reproductive rights, make statements early and often against abortion restrictions whenever they are pushed forward, and sit down with advocacy organizations to develop policies and hear firsthand the impacts that abortion limits have.

Hagstrom Miller points out, as a Democratic presidential candidate, his identity as a gay Christian man from a red state actually gives Buttigieg a unique and particularly strong opportunity to stand up clearly for abortion.

“People struggle with some of the same issues because they feel so judged and so shamed in our culture,” says Hagstrom Miller, who came to work on abortion through her own Christianity. “I see a path for him to talk about abortion just like he talks about being a gay Christian….There’s a through line here of compassion and of justice and of humanity.”

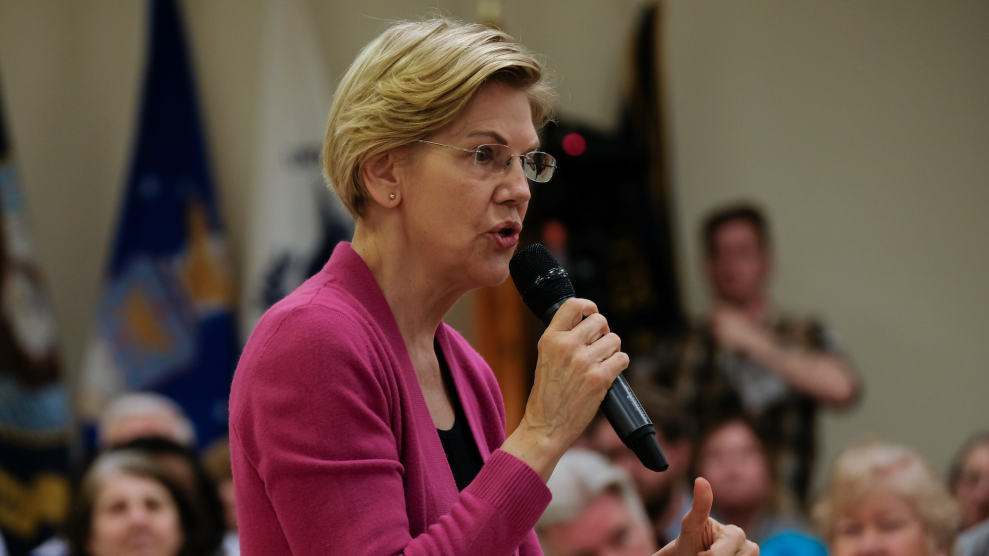

Image credit, from left: SAUL LOEB/Getty, Stefani Reynolds/Zuma, Scott Olson/Getty