Andrew Brookes/ZUMA Press

From late 2017 through 2018, Maciej Ceglowski—a tech entrepreneur and computer programmer—crisscrossed the country to educate Democrats on email security. Last fall, in an op-ed published by the Washington Post ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, Ceglowski referred to his effort to train the campaign staffers as “quixotic,” and relayed information security horror stories that he gathered visiting more than 40 campaigns. The column offered basic advice, such as replacing email attachments with cloud sharing, and to layer traditional email passwords with physical security keys that plug into computers.

Earlier this week Ceglowski posted to his personal blog a new piece with more detailed lessons from his travels. Ceglowski hopes to convey some basic truths about beefing up congressional campaigns’ digital defenses: Staffers are overworked, too focused on fundraising to let anything get in the way, and too reliant on convenience and speed to take information security as seriously as they should. We caught up with Ceglowski and asked him to share his thoughts on addressing the problem ahead of the 2020 campaign.

Mother Jones: Election security, as an issue, continues to land in the headlines. It was a key theme in the wake of the 2016 elections, and was front and center in special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russian influence operations. After all of that, do you get the sense that campaigns are taking this seriously?

Maciej Ceglowski: It’s a lot like preventative medicine. Even if you know that you’re at risk and that you need to take steps, it’s still hard to do psychologically. Another part of it is I don’t think anybody except Hillary Clinton paid a price for what happened in 2016. I don’t think people lost their jobs for failing to secure systems. I don’t think they’re bad people, but when you’re in my position you’re looking for any lever you can find to motivate and get people to do stuff. Looking to this election, nothing really happened in 2018 that was public. Nobody really went down in flames over campaign security. I think that’ll make it even harder to make that argument this time around.

MJ: What is it going to take?

MC: As long as we don’t have any sort of leadership from the top of the party or from Congress then I think that we’re setting people up to fail. We’re asking campaigns to follow all these really difficult steps to secure themselves, and then if something happens we’re basically going to be blaming the victim. That said, I do think a couple of really high-profile examples would—as much as I hate to see it happen—help very much to make the threat more real.

MJ: What are you thinking about campaign information security as we head into the 2020 elections?

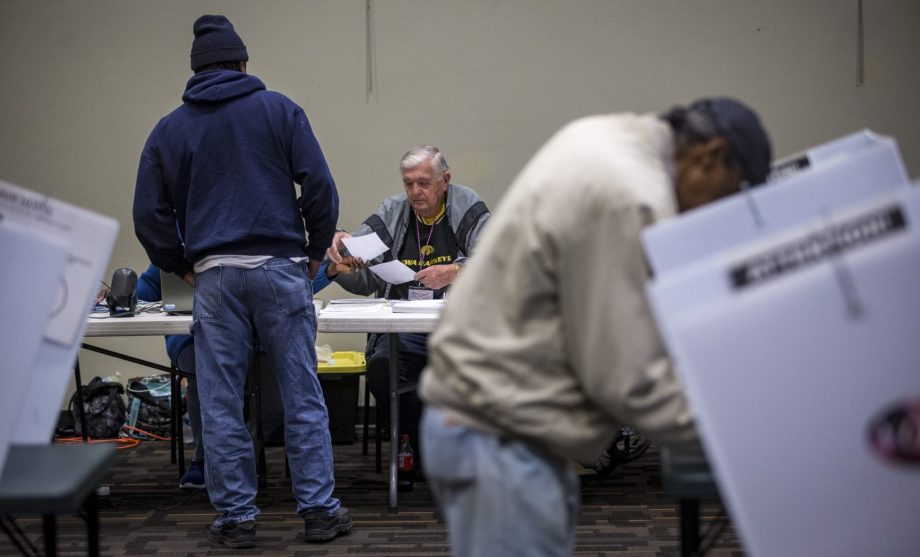

MC: We’re in a state of basic institutional paralysis. There’s no legislation moving, everything is on hold, and we’re in a paralyzed atmosphere. I’m looking at what’s happening with election security, where it’s even more of an emergency, and the fact that election security has become a Republican versus Democrat issue now kind of removes all hope that we can move together. In the past you can imagine how people would treat this as being an issue that was beyond party. But that’s not the atmosphere right now.

MJ: What is it about political campaigns that make them particularly vulnerable?

MC: The problem is that you have people who have no expertise and no training, no access to training, going up against people who are specifically targeting them who possibly have state backing. Everybody who has worked corporate IT knows these threats, malware and phishing; they’re very, very common. But the difference is in those places you’re not up against someone who’s specifically targeting you, that there’s possibly an office building full of people whose job it is to try and hack into your organization. So it’s a very elevated threat compared to what you see in other areas, but people are not going into it with any additional armor.

MJ: So what’s the way forward?

MC: You need a system where human beings go out and talk to campaigns. Systematize the stuff that I was trying to do, the stuff that DigiDems are doing, where they kind of embed people. You need a human point of contact and a way to escalate stuff so you can get rapid answers. We can’t keep sending people PDFs about how to secure their systems. They need hands-on help. And I don’t think it’s particularly expensive. We already have the structures that could do this, it’s just that there’s a lack of desire.

From the DCCC, the DNC, they’re entirely organized around fundraising, and fundraising is the elephant in the room with campaign security and a lot of the other structural issues effecting elections. It is so central to modern campaigning that it makes it impossible to do any of the other party-building or regional stuff that you would want to see, including making sure that there’s expertise available to people in these elections.

The political system is broken that way. But also the [information security and technology companies], frankly, are terrified by political blowback from conservatives. We have to admit that the threat is not symmetrical—Democrats are being targeted to a greater extent, given what happened in 2016, so anything that you do to secure campaigns is going to make you look like you’re trying to help liberal causes. The American right and far right have been very effective at scaring Google and Facebook and Microsoft into not doing anything for fear of being accused of having a thumb on the scale.

You don’t really want the Department of Homeland Security involved in this. They have a national cybersecurity center, but they’re such a highly politicized agency. Also, one of the strengths of our electoral system is the federal government doesn’t really have any contact with campaigns, except for filings.

The last group of people who could do this are PACs and advocacy organizations. You see this with some bigger organizations like Emily’s List and others who also run a security program with the campaigns that they endorse—but then once again you’re tying things into fundraising. There’s a way in which campaign finance laws really hinder our ability to secure campaigns, which is unfortunate.

MJ: What do you mean ?

MC: There’s some basic problems. Some of the states, Maryland, for example, have a rule that it’s out of bounds to try and secure personal accounts with campaigns funds, which I think is a terrible rule. The fact that you can’t have Google give special treatment to email accounts that are campaign-adjacent. You’d want to be able to flag them, to limit access, or certainly limit password reset or something like that, but none of this can happen because it’s proscribed by the same laws that don’t want corporations giving presents to candidates, for obvious reasons. But this is an area where you do want private industry to be able to give special treatment to political campaigns and there has to be a change in the legislation to enable it.

MJ: You’ve said personal accounts are a primary target, and referred to the infiltration of John Podesta’s Gmail account as a “template.” What do you mean?

MC: Podesta got tricked into typing his password into something that looked like Google and wasn’t. Other people around him and in Democratic leadership did the same thing. The attackers were able to use that point of entry to gain access to all of this interesting material. As an attacker what I want to do is find a way in and then I want to expand. So if I hack your account, maybe now I can get to your editor because I can send them something that flies under their radar because it’s coming from you. I can spend some time exploring who are your friends, who are your contacts, and make inroads wherever I can. As an attacker I don’t care whether I’m doing it through campaign people, through your ex-girlfriend, through your parents. All of these boundaries that we enforce on what is legal to pay for, what can we defend, they don’t matter to an attacker who’s trying to find their way in.

Also, people do a really bad job of compartmentalizing what is campaign-related and what is personal. On campaign accounts you have this dialogue where people gossip and say things, and we saw this in the Podesta emails. People forward stuff to their personal accounts all the time.

It’s not just what people might find when they hack into your personal accounts. There’s a real strong chilling effect that if you know that if you’re just a person who’s working on a presidential campaign that your entire social media and email history is up for grabs now by sophisticated state actors. That’s going to make you think twice about volunteering, about being a staffer, and that has really big effects on our democracy. You don’t want good people to be scared off because we can’t defend their digital lives.

MJ: There have been some institutional efforts to help campaigns. Google has offered an Advanced Protection Program for candidates (and journalists), and the Belfer Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School published an election security playbook. You specifically criticize those efforts in your writing as being non-practical. What’s the problem?

MC: My specific criticism of Google is that to my knowledge they did not field test with any federal campaign, and I think because Google legal wouldn’t allow it, that’s my guess. I think that Google is almost pathologically averse to having any sort of human tech support or giving a phone number. Even putting aside the campaign finance laws that make it difficult to do this, they just hate the idea of having a human in the loop because that’s not scalable, so they kind of have created this program from first principles, and then they’re surprised that they can’t get journalists and campaigns to use it.

The Belfer Center stuff has a different problem, which is that they didn’t want to recommend any specific vendors. And then they said things like for personal accounts, contact your favorite cybersecurity professional for advice, which is kind of like saying there’s a deadly flu going around and talk to a virologist for details.

The content of the stuff is really good. APP really is effective if you can use it, and the Belfer Center stuff is really spot on, except that nobody is intermediating between these golden tablets of holy writ and what people do day-to-day on the campaign.

MJ: When you talked with campaign staff about security issues, what surprised you most?

MC: I was really surprised at the number of campaigns that feel that they’ve been abandoned, not just in cyber security training but for anything. The extent to which in politics, people are written off even within the party, the extent to which there’s no ‘We’re in this all together’-solidarity, the lack of training, the complete emphasis on fundraising to the exclusion of absolutely everything else was really hard for me to see. It was really hard to see that all of the candidates I met who were trying to keep a day job failed. They couldn’t even with the primary. It’s just impossible to run for office if you’re not willing to spend. We have just a very, very badly broken system for electing people to office and it chews through people who have good intentions and it really favors people who are just massively rich or massively well-connected. Some of those people are great people, but it sucks to see it work the way it does.

MJ: You do spend time knocking the DNC specifically in your piece. What is the national party doing wrong?

MC: My understanding is that they think if you tell campaigns to share links to stuff that’s going to encourage phishing. So that if they were to share Google Docs all the time it would just be another avenue to phishing attacks. They’re like, ‘Let’s do attachments.’ I think this is really misguided. I think that if you can get security keys in place, the phishing threat is reduced, and the fact that you’re sending attachments to campaigns, it’s just such an obvious avenue for malware. With this kind of stuff you’re going to get the top-shelf malware, not just the crappy stuff. You might use something that is quite fancy, because you’re a state and that’s a high return on your investment. So I think they’re not really evaluating the risk enough. Again this is fundraising wagging the dog, because the need to send financials back and forth and all this data is just massive and anything that gets in the way of it is a non-starter.

MJ: So what should campaigns and the parties do?

MC: One idea I think could be interesting and could work really well is if we could have a red team that would try to hack campaigns, in a way that campaigns could agree to. They sign up and say, ‘Do your worst, try,’ and if we could have a way where they could actually be attacked and then that could be done early enough and often enough that they could learn to defend against it. We’re at the point where foreign countries and bad people elsewhere know more about our practical campaign security than we do, so I think it would be a project a lot of people would be really interested in from a security side, and I think campaigns would be happy to have that sort of expert assistance. I definitely think we should be doing this from within the country rather than just letting everybody do de-facto penetration testing from outside.