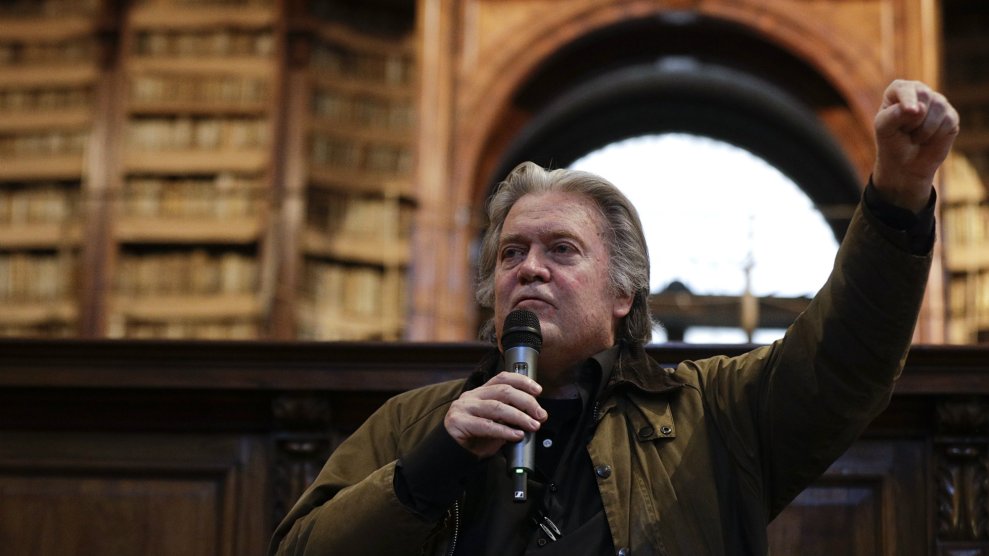

Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon speaks in Rome in March. He is a founding member of the Committee on the Present Danger: China.Gregorio Borgia/Associated Press

It’s been a rough couple of months for the image of the People’s Republic of China in the United States. Blistering government assessments have described China as a “persistent cyber espionage threat” and “strategic competitor.” FBI Director Christopher Wray even called the Communist country a “whole-of-society threat.”

But the conversation about China took a hard-right turn last month when nearly four dozen Trump allies, neoconservative thinkers, and scholars revived a Cold War–era group known as the Committee on the Present Danger to bring attention to what organizers call China’s “existential and ideological threat to the United States and to the idea of freedom.”

The geopolitical importance of China is a given, but two prominent members of this organization—Vice Chairman Frank Gaffney, the leader of a Washington think tank best known for promulgating anti-Muslim conspiracy theories, and former Trump campaign chairman Steve Bannon, who is back stateside after a failed months-long attempt to coordinate with Europe’s far-right political movements—suggest a motive that may be more personal than its promise to “educate and inform American citizens and policymakers.” These two men are not China experts but are links to both the Trump administration and populists worldwide.

Gaffney, once relegated to the fringe of the neoconservative movement, counts national security adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo as close allies. Bolton even tapped one of Gaffney’s deputies to join him in the White House as his chief of staff. (That aide, Fred Fleitz, lasted roughly five months before departing.) After his very public falling out with Trump, Bannon toured Europe attempting to form a “super-group” capable of dominating the continental parliament. The Brussels-based venture produced plenty of media coverage—even a cinéma vérité–style documentary—but not much in the way of tangible results. Bannon found more success in Latin America, where he’s become a close ally of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. Trump even warmed to his once-banished adviser recently, and mildly complimented him in a New York Times interview. Now Bannon is focusing on China.

“There’s a real threat, for sure, but the politicization of it is particularly dangerous,” says Graeme Smith, an expert on China at Australian National University. “To have these very divisive, very polarizing speakers leading the charge doesn’t bode well for a rational China policy.”

Their effort to raise the urgency of the Chinese threat is the culmination of an ongoing pivot among national security experts and government officials toward Beijing, after years when American entanglements in the Middle East dominated headlines, think-tank scholar research, and the activities of some of the more aggressive figures in the far right such as Gaffney. “At any given time, we need a particular existential threat to focus on,” Neysun A. Mahboubi, research scholar of the Center for the Study of Contemporary China at the University of Pennsylvania, says of American politics. Greater scrutiny of China is welcome in some corners of the American academic and business community, especially as the Chinese Communist Party grows increasingly repressive under the rule of Xi Jinping. But some experts believe the combination of overheated rhetoric from groups such as this and partisan bickering could distract from efforts to confront Chinese aggression in a measured, strategic, and bipartisan way.

With the Islamic State in decline and its physical caliphate eradicated, Gaffney and his allies faced a rhetorical vacuum, and the threat of China could easily be singled out as a clear and present danger. As long as Trump is president, his more visible allies will hold outsized influence—both at home and abroad—on setting the parameters of that conversation. Ratcheting up the rhetoric on one side could lead to a proportional response on the other. “The hawks on both sides are really giving each other what they want,” Smith says.

A little more than two weeks ago, the Committee on the Present Danger: China had its coming-out party with a roundtable discussion in a Capitol Hill ballroom. Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who is not a committee member but said he was “delighted” to have Gaffney’s “continued leadership on national security issues,” spoke in epic terms of a conflict enabled in part by the “insanity of the American news media” and complicity of the “academic left.”

“Anybody who tells you we are not losing is simply misinformed,” he said. “This is going to be a long-term struggle between a civilization that believes in liberty and a civilization that believes in authoritarianism with Chinese characteristics.”

The roots of this conflict precede Trump by decades. When American bombers destroyed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during a NATO-led air war over Yugoslavia in 1999, Beijing called it a “barbaric act,” and President Bill Clinton was forced to apologize. Two years later, a collision between a US spy plane and a Chinese fighter jet sparked another diplomatic spat. Only during the Obama administration, as China dispensed with the more cautious foreign policy of years past, did American officials begin viewing China not only as an economic competitor but a possible security threat. The failure of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Trump blew up shortly after entering office, cleared the path for China to build greater economic ties with its neighbors in the Asian-Pacific region.

Long an enthusiastic critic of China himself, Trump established a warm relationship with Xi upon entering office, a relationship that soon deteriorated after he initiated the trade war that has dominated the past several months of China-US relations.

Virtually no one in Washington disputes the severity of Xi’s aggressive foreign policy maneuvers or the depravity of his government’s human rights violations, but a consensus solution is in short supply. Democrats generally agree that China is a threat but have prioritized Yemen and Saudi Arabia as Congressional foreign policy priorities. And since Xi began his increasingly authoritarian rule in 2013, the US political and business establishment have not necessarily been eager to address the government’s theft of intellectual property or surveillance of its own citizens, given Beijing’s status as America’s leading trade partner. No such concerns troubled other featured speakers at the roundtable. “We have a healthy economy. The Chinese do not,” said Gordon Chang, a columnist who has long advocated for the US to abandon trade negotiations with China. “Disengagement will hurt, but it’s necessary.”

Given the unpredictability of the president, it is unclear if he will take the opportunity to lead on an issue that Democrats and Republicans equally acknowledge as a threat. “There have been a number of bills passed with bipartisan support—massive bipartisan support—that are critical of China,” Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California-San Diego, said at a recent lecture in Philadelphia. “This is one of those rare areas where we have bipartisan convergence.”

Should the Committee on the Present Danger be in a position to actually shape US policy, its extremism could create a host of new problems. The group includes several scholars and Chinese dissidents, but the presence of Bannon and Gaffney suggests that a measure of simple opportunism is driving the committee’s first steps more than the desire for an open foreign policy debate.

“To translate straight from your concerns about Islamic terrorism to your concerns about China is absurd,” Smith says. “Their credibility on this issue is practically zero.”

Gaffney, a strong supporter of Israel who once championed a study that said “more than 80 percent of U.S. mosques advocate or otherwise promote violence,” introduced Uyghur activist Salih Hudayar at the roundtable for a talk about China’s repression of religious activity and crackdown on the Uyghur Muslim minority. Key Trump advisers like Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Vice President Mike Pence have criticized China frequently for its detention and surveillance of the Uyghur population in the western Xinjiang province. Hudayar defended the idea of carving out a separate state specifically for Uyghurs and urged attendees to boycott “Made in China” goods and divest from companies that benefit from them—an idea reminiscent of the Palestinian boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement, which Gaffney’s think tank has called a “reinvented form of Anti-Semitism.”

China has not yet fostered the kind of anti-American rhetoric that might be expected in a country US officials so obviously consider a strategic rival. But with the fringe right coalescing around China as a new threat, and China itself becoming emboldened in its authoritarian activity, tensions between the two countries are likely to escalate. The roundtable concluded with a fiery rousing speech from Steve Bannon, in which he bashed the “globalist elite” for ignoring “the greatest existential threat we’ve ever had.” Qiao Mu, an exiled Chinese academic and human rights advocate, echoed the pessimism among experts in an email to Mother Jones. “I do not know the final result,” he said, “but obviously, the competition, or new Cold War, is on the way.”