Casino developer Steve Wynn and his wife, Andrea Hissom, make their way to the Senate Policy luncheon in the Capitol on June 27, 2017. (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call) (CQ Roll Call via AP Images)

In 1963, when Carole Whitehead was an unwed 18-year-old mother in New York, she placed her baby up for adoption. This had always been the plan, but she asked for the record to be open so that one day, if her son was interested, he would be able to contact her.

“Don’t tell me I want confidentiality,” Whitehead remembers telling hospital staff. “I don’t want confidentiality.” But the process was unclear, and she felt forced into handing over her child to an adoption agency without being informed of her legal rights. “I wasn’t promised confidentiality,” says Whitehead, who is now an adoptee rights advocate. “We never asked for it.”

Staff at Louise Wise Adoption Agency handled the surrender and placement of Whitehead’s child and likely told her that, as a birth mother, there would be “confidentiality” no matter what she said was her preference. This assurance was routine at the time.

Indeed, many birth mothers report they didn’t choose and weren’t legally guaranteed lifelong “anonymity” from surrendered sons and daughters, says Gregory Luce, a lawyer and founder of the Adoptee Rights Law Center, based in Minneapolis. As a result, many of those who support the status quo believe the original birth certificates of adult adoptees should remain sealed forever, and assume there is lifelong “anonymity” for birth parents. Adoption agencies, lawyers, or others in the industry may have offered birth parents short-term “confidentiality” or “privacy” to protect them from anyone finding out about the pregnancy, but any suggestion or insinuation that birth parent “anonymity” could be maintained forever is incorrect.

Even though the practice of lifelong anonymity has no legal standing, it has dominated adoptions since 1935. Until that point, most U.S.-born adoptees had unrestricted access to the records of their birth. After 1935, adoption agencies offered “confidential” or “closed” adoptions, in which there’s no contact between the birth and adoptive families while the adoptee is a minor. But adoptees of all ages, in states where the right to access their original birth certificate has not been restored to them as adults, continue to have the option to petition the court for a copy of this document.

States then started to seal original birth certificates once the adoption was finalized and issued an amended version to appear as if the adoptive parents had given birth to their adopted son or daughter. This began a clandestine process that politicians and supporters first presented as a way to protect the child from any perceived stigma of being adopted and later would present as a way to protect adoptive families from birth mothers who might meddle in their newly created or expanded families.

For most adoptees seeking to unseal their records, this practice has resulted in a difficult and costly journey should they ever attempt to get a copy of their original birth certificate. With no federal law dictating access to adoption records, the matter was left up to the states, where there is a patchwork of vastly different laws, none of which are based on any unifying legal precedent. Today, in statehouses around the country, a diverse and growing movement of adoptees, birth mothers, adoptive parents, and others — who see restoring unrestricted access to records of adult adoptees’ birth, like their original birth certificate, as an essential civil right — is pushing lawmakers to consider measures to enact what is known as “clean” adoption reform.

While no one knows for sure how many Americans are adoptees, the University of Oregon’s Adoption History Project estimates there are 5 million Americans alive today who are adoptees. In the 1970s, adoption rights activists attempted to change laws and make it possible for adoptees to regain unrestricted access to vital records, including original birth certificates. Activists argued it was important for them to understand their biological history, and the difficulty in accessing birth certificates was burdensome and discriminatory. No other American is required to get a court order to access this basic document.

The movement took hold in some states but not others. In nine states, adult adoptees can apply for and obtain their original birth certificate without any restrictions. Twenty-two states, including South Carolina, limit access through various measures, such as allowing a birth parent to deny the release of an original birth certificate or redacting information on the document (even though there are no laws promising anonymity to birth parents). In New York, 18 other states, and Washington, DC, where these records remain sealed, the only option for adoptees is to petition the court, which can be costly and has no guarantee. Whether a court petition is successful or not, adoptee rights activists say the process fails to recognize the basic right to access vital personal records of one’s own birth, and is inherently discriminatory.

All over the country, there are various efforts to restore the rights of adoptees. In states where laws that restore access have been challenged, courts have rejected arguments that birth parents have a constitutional right to privacy or anonymity in the context of the adoptee’s own birth record. New York, Texas, and Florida are all looking at restoring access to original birth certificates of adult adoptees to varying degrees, ranging from “access with restrictions” to “unrestricted access.”

In Florida, for instance, a bill was filed this year that adoptee rights advocates say is badly flawed because it makes access to original birth certificates dependent on birth parent involvement. If HB597 passes, adoptees will have to apply through the Florida Adoption Reunion Registry and connect with at least one birth parent before being allowed to apply for a copy of their original birth certificate. Currently, adult adoptees in the Sunshine State who want an original birth certificate must first be in reunion with a birth parent who consents to the release or obtain a court order.

Some adoptee rights advocates refer to Florida’s bill as “dirty,” because an adult adoptee’s access to their original birth certificate is restricted. In contrast, New York recently introduced a “clean” bill that will restore the rights of adoptees to get a copy of their birth certificate when they turn 18. If it is passed, beginning January 15, 2020, adult adoptees will have the same level of access to their birth certificates that non-adopted individuals may take for granted.

Even with more than 80 Assembly co-sponsors, and top adoptee rights groups like the American Adoption Congress, the National Center on Adoption and Permanency, and the North American Council on Adoptable Children supporting the measure, there has still been opposition. Birth mothers and elected officials who see the mothers’ right to privacy as paramount—though lifelong anonymity from surrendered sons and daughters was not legally guaranteed—have tried to prevent the legislation from passing.

“This issue shouldn’t be about anyone or anything else other than an overdue recognition of basic human rights,” says Tim Monti-Wohlpart, a New York adoptee who serves as the National Legislative Chair, and New York state representative, for the American Adoption Congress, where he helped cement a formal legislative policy for “clean” reform. He also started a grassroots petition to advance the New York bill. He attributes any lingering opposition to the legislation to fear, and suggests that while some adult adoptees may prefer not to request a copy of their original birth certificate or records, they should still have a right to access them if they ever changed their mind. “New York does not simply have a policy of sealed records, but also a culture of secrecy,” he says. “The remedy is adoptee equal rights.” If the law is changed, each adoptee would have a range of options, “from no action, to retaining a birth certificate for their personal files, to completing a search” for their family members.

Luce, from the Adoptee Rights Law Center, points out another potential problem for those who oppose legislation for unrestricted access to adult adoptees’ original birth certificates. He says no promise of anonymity could legally have been made because there was never a guarantee the child would actually be adopted. In those cases, the adoptee would always have access to their records, or that if a judge believes there is cause to do it, courts can unseal adoption records. Luce, an adoptee, knows this process all too well. He successfully petitioned a court for his original birth certificate in Washington, DC, where he was born in 1965 and adopted at a week old. But he’s now challenging the redaction of his birth father’s name on the document because his birth father didn’t give consent. Luce says he already knows this information from his birth mother, with whom he had met before her death.

Only during the appellate process are these issues sufficiently narrowed, demonstrating, according to Luce, the distinction between “all this emotional stuff” involving reunions, but “about the record itself.”

This difference in state laws can compound the frustrations experienced by adoptees who must work with multiple state agencies. Erica Babino, the former national legislative chair for the American Adoption Congress, was born 55 years ago in New York but was adopted in Texas. When she was 25, she tried to gain access to her original birth records, a process that lasted for 25 years. On one visit to New York, Babino sobbed while a social worker sat inches from her with a file that contained her birth records but did not permit her to see them. She managed to find her birth family, but the records in New York remain inaccessible to her.

“There’s absolutely no reason why an adult cannot make a decision about their own lives and to be able to have their original birth certificate just like every other American,” she said.

For those who believe that the records should be sealed, protecting mothers, who may have not wanted their past revealed is often cited as the main reason. Advocates for women who have experienced traumatic, unwanted pregnancies, like author Kathleen Hoy Foley, say there are dangers in exposing these women unilaterally. In her written statement to the New Jersey legislature when an open-records law was being debated in 2011—the measure eventually passed three years later—she stated: “All women in hiding are petrified of the betrayal of such private and personal information…and all the same and anguish such exposure carries with it.”

A small number of opponents, mainly Catholic groups, argue that some birth mothers may have opted for abortion rather than adoption if they thought their identities would be revealed. The American Adoption Congress says this has not been the case. “The data reveals that if access has had any effect on adoptions and abortions, it’s been to increase adoptions and decrease abortions,” the group noted.

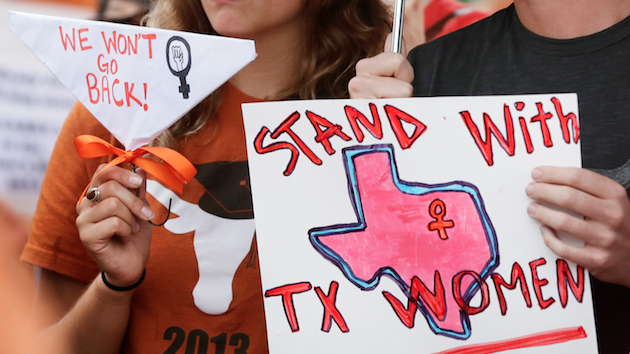

In Texas, one state senator has successfully blocked open access laws repeatedly for other reasons. Donna Campbell, a physician and adoptive mother, claims adult adoptees may want to find their birth mother for “financial reasons.” Shawna Hodgson, co-founder of the Houston-based Equality4Adoptees organization, has worked with adoptees throughout the country to bring an open-access measure to the Texas legislature and says that despite overwhelming support, similar bills filed in 2015 and 2017 were eventually killed by Campbell, a close political ally of Senate President Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick.

Historically, the National Council for Adoption has opposed the types of unrestricted access currently proposed across the country, and for the past few years hasn’t waded into the debate. But today, the nearly 40-year-old organization says it supports legislation that balances the needs of adult adoptees and their birth parents. Its president and an adoptive father himself, Chuck Johnson said the organization backs programs that use trained “confidential intermediaries” to discreetly contact birth parents or adoptees to see if they want to reunite, and leaves open the option for birth parents to decide whether they want to be contacted by an adoptee. “We support people who want to be contacted and allow ways to make that happen,” he said.

Being unable to access these records has often led adoptees to use social media and DNA testing services for answers. But advocates say this doesn’t replace access to original birth certificates. Adult adoptees who are not able to obtain a copy of their own original birth certificate may also be denied driver’s licenses and other government identity documents.

Carole Whitehead is 74 years old and works as a cancer registrar—a data information specialist for cancer patients in Plainview, New York. She has been involved with Unsealed Initiative, New York’s largest lobby for adoptee rights, for years. She never had access to her son’s records. But in 1985, with the help of a private investigator, she found Paul Dinberg, in Long Island. He was living only five miles away from where she lived at the time. When she drove up for their first meeting, he was sitting on the stoop in front of his house. “I waited 22 years for this,” Whitehead remembers telling her son during their emotional reunion. “I told him that I was his mother.”

Since then, Whitehead has remained in contact with her son, even attending his wedding with her husband and her two other children. Dinberg is now 54 and lives in Oregon with his two daughters and a stepdaughter. “He calls me Mom,” she said. “We’re family.”