Central American refugees wait outside an Immigration and Naturalization Service processing center in Brownsville, Texas, in 1989. Shelly Katz/Getty

In January 1993, a Pakistani asylum-seeker drove to the entrance of the CIA’s Virginia headquarters, pulled out an assault rifle, and murdered two of the agency’s employees. A month later, terrorists bombed the World Trade Center, killing six people and injuring more than a thousand. One of the perpetrators had also requested asylum.

Bill Clinton had been president for five weeks, and the asylum system was facing an unprecedented crisis. Dan Stein of the anti-immigrant Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) falsely claimed on an influential 60 Minutes segment that only 1 or 2 percent of asylum claims were legitimate. Rep. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) called America’s asylum system a “laughingstock.” Sounding almost indistinguishable from President Donald Trump today, Schumer said, “These terrible gangs can tell people, ‘We know how to get you into America. Just read this card that says “I want amnesty” and you’re in.’”

The main problem facing the asylum system was a massive and ever-expanding backlog of cases. That backlog, together with a policy that made asylum-seekers immediately eligible to receive work permits and a limited capacity to keep track of asylum-seekers allowed into the country, gave immigrants an obvious incentive to submit weak or fabricated claims. In 1992, the Immigration and Naturalization Service received 104,000 asylum applications but processed only a fifth of them. By 1994, the asylum backlog stood at more than 420,000 cases. Many of those were strong claims, but the delays were undermining the entire system’s legitimacy.

Legislators argued that fundamental changes were needed. Rep. Bill McCollum (R-Fla.) proposed making it easier to turn asylum-seekers away at airports or the border, citing a “Paki fellow” shown in the 60 Minutes broadcast two days before. Schumer endorsed a requirement that people apply for asylum within 30 days of arriving in the country, a deadline many were unlikely to meet since asylum claims required submitting substantial paperwork after being temporarily allowed into the United States, often without legal assistance.

Today, opponents of immigration are again citing asylum backlogs to justify gutting protections for people fleeing persecution. There are no studies backing up their claims about widespread fraud, but it’s true that the asylum system is overwhelmed. Chronically underfunded immigration courts are facing a backlog of more than 800,000 cases, about a third of which are asylum cases.

Some asylum-seekers wait years for their cases to be heard. Since asylum-seekers don’t become eligible to bring immediate relatives to the United States until they’re granted asylum, they’re effectively separated from their families during those long waits. But the backlog can also provide an incentive to file weak asylum claims, since there are often yearslong periods when asylum-seekers can legally work in the United States.

The Trump administration has hired more immigration judges, but like previous administrations, it has spent far more resources on enforcement and deterring people from coming to the United States. It now says it will make asylum-seekers wait in Mexico for years while their US asylum claims are pending. It announced a plan to bar people from receiving asylum if they cross the border without authorization, although that policy has been blocked in court because it violates a law that allows migrants to apply for asylum regardless of how they cross the border. No administration has ever made asylum—once a niche issue—so central to its agenda.

In response to its own asylum crisis, Clinton’s INS responded with seemingly technical fixes that Stein initially dismissed as “internal administrative games.” But they did what they were supposed to do. The number of new asylum claims plummeted, while the proportion of successful applications more than doubled. The backlog stopped growing and was eventually all but eliminated. As the Trump administration focuses on punishing asylum-seekers, the Clinton-era reforms provide a framework for a more humane response to today’s challenges.

When David Martin worked in the Jimmy Carter administration, the INS tended to follow recommendations from the State Department about which countries’ émigrés were deserving of protection.* Seventy-eight percent of Russians got asylum in 1983, compared to 3 percent of the Salvadorans fleeing a US-backed regime. The George H.W. Bush administration responded to that flawed system by creating a dedicated asylum office, but it opened with only 82 officers. Switzerland had about 500 people vetting one-fifth the number of claims, Newsday reported in 1993.

The asylum officers often had backgrounds in human rights work. After Martin went back into government work and joined the INS as a consultant in 1993, he was struck by how fed up those officers were with “boilerplate” applications submitted by unscrupulous consultants who filed false asylum claims so their clients could legally work while their cases sat in the backlog. Martin says one application might say an asylum-seeker was targeted in his home country by assailants in a Ford Falcon; another would cite a green Falcon; a third, a red Falcon. “It wasn’t clever,” he recalls. “Somebody who was viewing several of these a day quickly sees this is exactly the same claim, maybe with a few changes of adjectives.” The asylum officers believed the false filings were sinking the system to which they had dedicated their careers.

Martin worked with human rights groups to find a solution. Together, they proposed expanding the asylum officers corps and deciding new asylum claims before those in the backlog. To the dismay of immigrant advocates, the INS also called for blocking asylum-seekers from getting work permits for six months and charging them an application fee. These policies allowed the INS to finish new cases before asylum-seekers became eligible for work permits.

Bill Frelick, who is now the director of Human Rights Watch’s refugee program, recalls that one of the main concessions from advocates was simply admitting there was a problem. There was no time, he says, to take a dogmatic “on the side of the angels” position. They needed to show legislators that administrative changes, not harsh laws, could fix the problem.

Immigrant advocates succeeded in getting the INS to drop the application fee, but not the waiting period for work permits. Still, compared to today, there was little resistance. Congress provided the money for hiring asylum officers. No one sued. Georgetown Law professor Philip Schrag, who wrote a history of the congressional battle to save asylum, says the reforms were “put into place by broad consensus, the kind of consensus that nobody even tries to form anymore.”

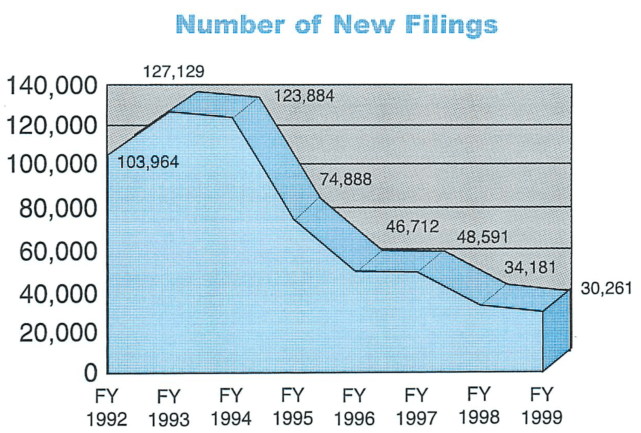

Asylum applications fell by more than half between 1994 and 1995, and the vast majority of applicants were getting decisions within six months. By 1999, annual asylum claims had plummeted even further as the approval rate more than doubled to 38 percent. The average asylum claim had become much stronger, and the widespread concern about people filing false claims was largely eliminated.

A chart of asylum applications handed out at the five-year anniversary party. The reforms were announced in October 1993, the start of the 1994 fiscal year, and went into effect in January 1995.

Courtesy David Martin

Everyone seemed pleased. The Justice Department, which oversaw the INS, marked the five-year anniversary of the policy changes with what Martin calls a “birthday party.” Eleanor Acer, the refugee protection director for Human Rights First, told Congress in 2001 that the reforms were a “tremendous success.” The right-wing Center for Immigration Studies, a FAIR offshoot, published an article by Martin describing the changes as among the “most successful the immigration system has known.”

By the time Barack Obama became president, the asylum office’s backlog was essentially gone. But as unprecedented numbers of Central American families and children fled rampant violence, it exploded once again. Acer and others quickly called for hiring more immigration judges and asylum officers to keep up with the influx, but the Obama administration did not hire enough. When Obama left office, the asylum office had more than 220,000 cases pending, up from about 6,000 in 2010. Many more claims were making their way through increasingly backlogged immigration courts.

The court backlog now exceeds 800,000 cases, and the average case has been pending for nearly two years. Immigrant advocates are frustrated that the delays strand relatives of asylum-seekers abroad for years, often in dangerous countries. Critics of immigration note that the long waiting period gives people with weaker claims the ability to work legally in the United States for years before their cases are heard. The status quo vexes both anti-immigrant groups fixated on potential fraud and human rights organizations that want clients with strong cases to receive legal status quickly.

Back in the ’90s, when she led the INS, Doris Meissner talked about combating frivolous claims. These days, she prefers to avoid the term; she sympathizes with people in dire circumstances who are unlikely to qualify for asylum. Poverty, no matter how intense, is not grounds for asylum, and Meissner argues that asylum is not the answer for all the “deeply, deeply urgent matters” people are fleeing. “But when they are facing really bad choices and you have systems that are dysfunctional, yeah, they’ll try it,” she says. “Any of us would.”

Meissner believes that timely asylum decisions would function as a form of deterrence, just as they did in the 1990s. Schrag hasn’t seen any empirical evidence that the ability to get a work permit for years before an asylum ruling is causing large numbers of migrants to make weak asylum claims. But if that is the case, he says, getting rid of the backlog would eliminate the problem.

Last January, US Citizenship and Immigration Services, which handles some asylum applications, returned to the Clinton-era policy of prioritizing new asylum applicants over those already waiting for a hearing. The backlog has stopped growing since then, although it’s unclear how much credit should go to the switch. Other factors may also be playing a role: For example, the number of visas issued to Venezuelans, who often apply for asylum after entering the country on temporary visas, has dropped dramatically.

Meissner, now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, co-authored a report in September calling for additional reforms to streamline asylum decisions without undermining due process, such as handing over some cases from immigration judges to dedicated asylum officers. Acer of Human Rights First stresses the need to hire enough immigration judges and asylum officers to decide cases in a timely manner. And immigrant advocates have long argued that giving asylum-seekers access to legal counsel would make immigration courts more efficient and fair. Like the reforms the INS implemented in the 1990s, these proposals aim to eliminate backlogs, not punish people.

That may be their biggest pitfall. Trump and the White House are “completely impatient,” Meissner says. “This is a solution that would take time. There’s nothing sexy about it, and this White House wants shock and awe.”

Quicker decisions on asylum claims carry another risk: They give the administration more power to deport people promptly, rather than allowing them to live and work in the United States while awaiting a ruling. Last year, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions used his broad authority over immigration courts to make it harder for people fleeing gang and domestic violence to qualify for asylum. The decision, which disproportionately impacts Central Americans, will likely cause asylum-seekers to be sent back to countries where they face life-threatening persecution.

Asked whether advocates want to work with the government again to head off the need for harsh new laws, Acer says the question assumes that the administration actually wants the asylum system to work. “The motivation from the Trump administration is to block asylum-seekers from the country,” she says. “And, frankly, it appears to be to mismanage the asylum system as much as possible to justify efforts to block refugees.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the administration in which Martin worked.