Mother Jones illustration; Mark Humphrey/AP

Earlier this year, a mere five months after the #MeToo reckoning first began, a local Tennessee television station dropped what should have been a bombshell investigation: Three women were accusing state Rep. David Byrd of sexually assaulting them when they were minors in the 1980s, using his position as a girls’ basketball coach to prey on players during team trips and after practices.

Despite the seriousness of the allegations, the response within the state capital was, in a word, muted. Speaker of the House Beth Harwell and Lt. Gov. Randy McNally, both Republicans, called for Byrd, also a Republican, to resign, as did Democratic Rep. Sherry Jones and a few other Democrats. But that was it—no investigations, no protests, no official action whatsoever. By the end of the legislative session in April, just a few weeks after the investigation first hit, the calls for his resignation had dwindled, and Byrd had announced he’d run for a third term in November.

He overwhelmingly won reelection, with nearly 78 percent of the vote.

Over the past year, powerful men who abused their power for far too long have continued to fall across the country, but in places like Tennessee’s 71st District and others like it—rural, deeply religious, and proudly traditional—change has, unsurprisingly, been harder to coax along. The Tennessee state government, at least, has long been operating a culture of secrecy, and while two lawmakers have been removed from office in the past few years due to sexual misconduct, they may prove to be the exception rather than the rule. A 2016 investigation from the Tennessean found that the Legislature’s longtime confidentiality policy regarding sexual misconduct complaints prevented even broad data about harassment from being released. Following that news report, a new sexual misconduct policy was implemented to promote greater transparency, and sexual harassment training was mandated for all Tennessee lawmakers. Many of them took it less than seriously, reportedly cracking jokes during the presentation.

The incident with Byrd shows just how limited the system still is. Because his alleged misconduct happened long before his time in government, the Legislature, even with its new policy, has largely been able to shirk responsibility.

Byrd has not exactly denied the allegations against him; rather, he emphasizes repeatedly that they are from more than 30 years ago. In a statement to the press earlier this year, he only said that he is innocent of any wrongdoing since he was elected to office in 2014. “These recent allegations of inappropriate contact, never before made, date back over three decades ago and are disheartening to me, and my family,” Byrd wrote in a statement to Nashville television station WSMV shortly before its investigation ran. “One must question the motives of these three former students out of the hundreds of students I have coached.”

“Conduct over 30 years ago is difficult, at best, to recall, but as a Christian,” he added, “I have said and I will repeat that if I hurt or emotionally upset any of my students I am truly sorry and apologize.”

Byrd did not respond to a request for comment from Mother Jones.

For Christi Rice, the public apology didn’t mean much. She says that high school was hard enough before Byrd began to abuse her. She was a devoted basketball player, turning to the sport to help her cope with some prior trauma. “Basketball was my safe place, and he destroyed that,” she says now.

As a 15-year-old freshman, she initially “worshipped the ground [Byrd] walked on.” At first, any attention she got from him was welcomed. But the summer after her freshman year, on her way to a basketball camp with the team, their relationship changed. She recalls catching him staring at her in the rearview mirror as he drove the bus, and though something felt wrong in his smile, she dismissed it. Sometimes, when he guarded her at practice, she thought she saw him looking down her shirt, but she dismissed that, too.

“Honestly, I don’t remember the very first time he touched me,” Rice says. “It was more that he talked about it: He wanted to see me naked, he told me he spent more hours with me in a day than he did his wife, that when he had sex with her he was thinking about me.”

Rice tells Mother Jones that she remembers Byrd leaving her what she calls IOUs, that insinuated she owed him a sexual quid pro quo. The first came the morning after a late-night basketball game that prevented her from being prepared for a surprise biology test the next morning. Byrd, who was also Rice’s biology teacher, told her she didn’t need to worry when she fretted to him about her potential score. When the test landed on her desk, she said, the answers were already filled in. Shortly thereafter, she received the first IOU, signed with his initials, “DAB.” For weeks, he teased her, saying she owed him, but he hadn’t decided precisely what her payment would be. Eventually, he told her: Rice was to disrobe in the girls’ locker room after her teammates had gone home so he could “accidentally” walk in on her. The second, Rice says he told her, was for her to unbutton her shirt and lean over in front of him, pressing her breasts together.

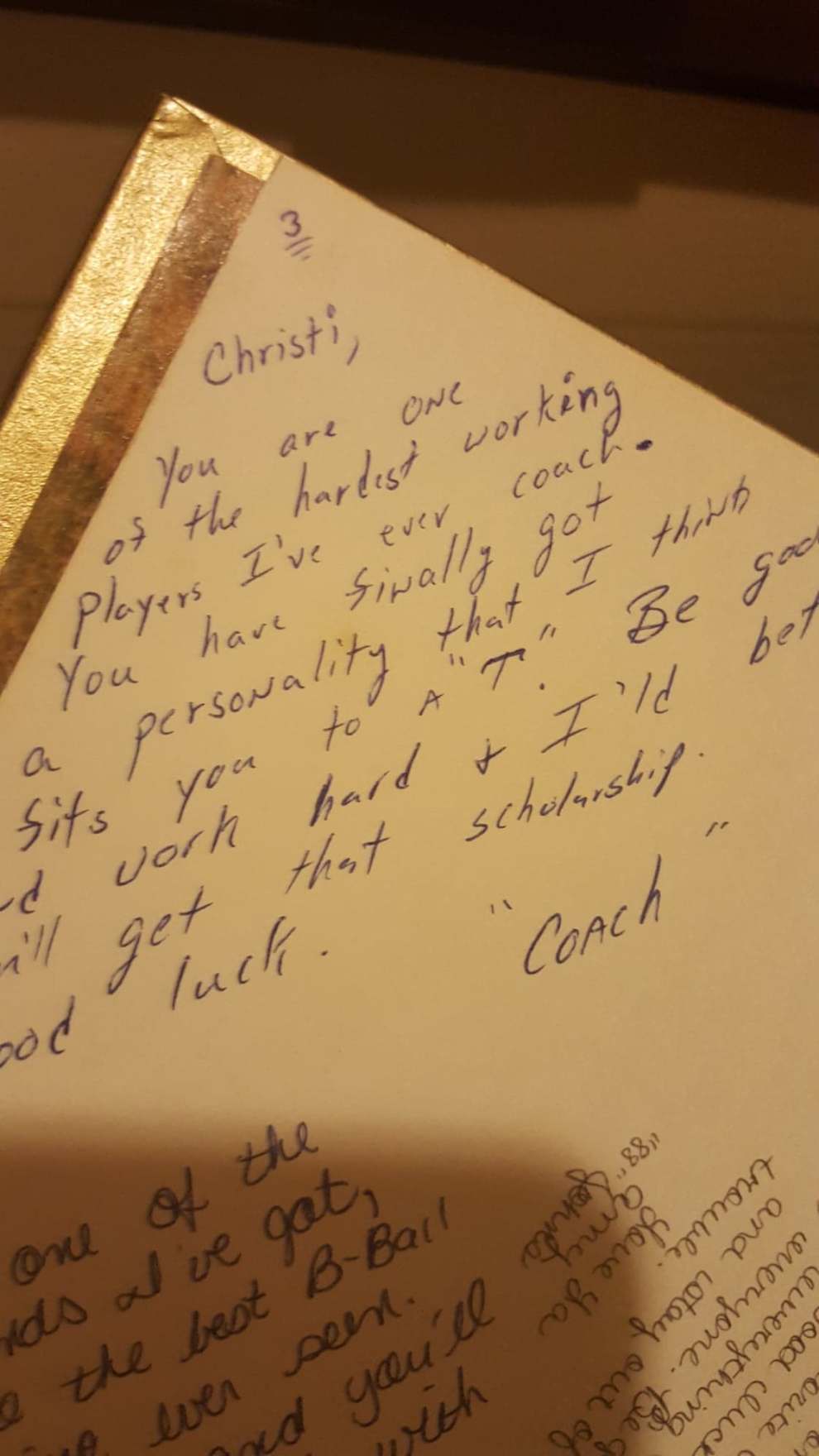

The third he inscribed as a note in her yearbook. It reads, “You are one of the hardest working players I have ever coach [sic]. You have finally got a personality that I think fits you to a ‘T.’ Be good and work hard and I’ll bet you get that scholarship. Good luck.”

It’s signed simply, “Coach.” Above the inscription, the number three is written, underlined three times.

Rice says he told her it was for sex.

When local television station WSMV broke the misconduct allegations this spring, Rice reported that over the course of her sophomore year, they kissed 10 times, mostly on school property. He touched her breasts, and once, he pulled her hand toward his groin while he kissed her. According to Rice, it only ended after Byrd pulled her into a hallway at school and told her that a bus driver, who was also a relative of Byrd’s wife, got suspicious and told Byrd’s wife she felt like something wasn’t right between the two.

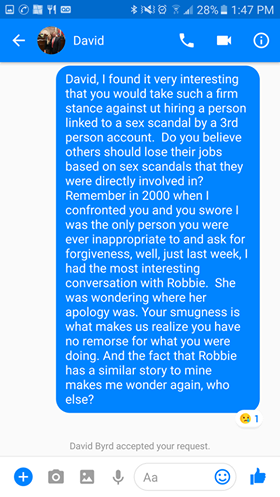

Rice never reported Byrd. Then in February 2018, she saw a Facebook post from him, by then in public office for four years, pledging he would “voice the concerns of [his] constituents” regarding the potential hiring of Greg Schiano as a University of Tennessee football coach. Schiano allegedly failed to report sexual abuse by Jerry Sandusky while he was an assistant football coach at Penn State. (Schiano denies the allegation.) For Rice, it felt like the ultimate hypocrisy. Spurred on by the #MeToo movement, she sent him a Facebook message.

“Remember in 2000 when I confronted you and you swore that I was the only person you were ever inappropriate to and ask for forgiveness, well, just last week, I had the most interesting conversation with Robbie [Cain],” she wrote. “Your smugness is what makes us realize that you have no remorse for what you were doing. And the fact the Robbie has a similar story to mine makes me wonder again, who else?”

Byrd replied, asking her to call him. Rice did, and she recorded their conversation.

“I can promise you one thing, I have been so sorry for that,” Byrd says in the recording. “I’ve lived with that, and you don’t know how hard it has been for me.”

In the recording, Rice confronts Byrd about other women who say they were also molested by him, and Byrd denies there was any misconduct with any other girls.

Byrd has been publicly accused of similar behavior by two other women—Robbie Cain, whom Rice was referring to in her Facebook message, and another who wished to remain anonymous, but who told her story to WSMV in the spring.

Cain told WSMV about an incident during the summer of 1986, when she was alone in a hotel swimming pool while on a trip with the basketball team and Byrd tried to touch her genital area, and encouraged her to touch his. But Cain tells Mother Jones the abuse she experienced goes far beyond what was published in that report. She recalls Byrd asking her for “ABC gum,” an acronym for “already been chewed”—in other words, he wanted her to transfer the gum from her mouth into his. Later, he inscribed into her senior yearbook, “To the girl who could not dribble and chew gum at the same time.” Years later, long after she had graduated, she ran into him at a restaurant, and he repeated the phrase to her: “The girl who could not dribble and chew gum at the same time.”

She adds that as a player, she struggled with pain in her ankles. On occasions when the pain was overwhelming, Byrd would carry her into the basement of the high school, where he would instruct her to take off her pants and get into a hot tub, he told her, to ease her ankle pain.

Cain, in searing detail, also recalls that particular night reported by WSMV at the Sheraton Hotel in downtown Nashville—”I’ll never forget it in my life,” she says. The girls’ basketball team was staying there, and she went with her teammates into the pool for a swim. She says Byrd joined them, but one by one, the other girls left the pool, until it was just her, alone with her coach.

“The next thing I know, he’s got me over on the side of the pool, and he’s telling me he wants me to reach down and touch him between his legs because he wants me to feel how I make him feel—he kept telling me how it’s throbbing,” Cain tells Mother Jones. “I was like, ‘No, no, no.’ I just remember screaming, ‘No,’ and getting out of that pool.”

A third woman who spoke to WSMV but did not return calls from Mother Jones described similar behavior. She said the misconduct also happened on a basketball trip when she was 16. After seeing another player go into Byrd’s hotel room, she followed. Eventually, he had her lay down on the bed and massaged her.

“When I laid down he positioned himself to where his penis was between my butt cheeks and he started rubbing my back and then he put his hands under my shoulders to rub me, and he went to the sides of my breasts underneath my arms,” she told WSMV.

Byrd, who was the head coach of Wayne County High School’s women’s basketball team for 24 years, was later promoted to principal of the school; he held the position for eight years. Byrd’s nephew, Ryan Franks, is now the principal of the school. Over the past four years, Byrd has hosted seniors from the six high schools in the district for a “Senior Day at the Hill” in the state Legislature.

When the allegations were first published, some Republican leaders, such as Harwell and McNally, were reportedly horrified and called for Byrd’s resignation. But most of his other peers either declined to take a public stance or defended Byrd’s position. Republican House Majority Leader Glen Casada initially said that although “the women have a right to be heard,” so does Byrd, and he should not resign. Gov. Bill Haslam, also a Republican, refused to comment on the matter, other than to say that “the voters in his district from his party are going to get to decide.” It was, after all, an election year.

During the campaign, Byrd emphasized his political connections and trustworthiness; a mailer went out that showed then-gubernatorial candidate Bill Lee, who won the governorship, posing for a photo with Byrd. It said, “David Byrd: A Leader We Can Trust.” Lee later told the press he didn’t authorize the mailer, which bears the return address of the Tennessee Republican Party, but he did not say he disagreed with the sentiment. (The photo is also featured on Byrd’s Facebook page, taken at a campaign event with Lee.) In April, Lee told the Tennessean in a statement that while the allegations are “troubling,” he felt it would be wrong to “rush to judgment.” Meanwhile, Byrd’s Democratic opponent, Frankie Floied, never even mentioned the misconduct allegations during the campaign and gained little traction in the district.

(One politician who actually stands apart in calling out Byrd is the Republican firebrand Rep. Marsha Blackburn, who won a US Senate seat in November. In April, she called the allegations “particularly disgusting and shocking,” and she refused to campaign with Byrd even after he endorsed her.)

Amid this inaction came a new group highlighting the misconduct claims: a super-PAC, called the Enough is Enough Voter Action Project, run by Michele Dauber, who led the campaign to recall the judge who made headlines for the Brock Turner sexual assault case. The group’s mission has been to target men running for office across the country who have been accused of sexual misconduct, including Byrd. Starting in September—with the support of outgoing Democratic state Rep. Jones, who had previously called on Byrd to resign, local Indivisible groups and Power Together, Tennessee’s chapter of the Women’s March—the PAC aired ads and sent out mailers detailing Byrd’s behavior.

Enough is Enough also organized a canvassing effort to educate people about the allegations. Going door to door, they were surprised to find several locals describing Byrd’s behavior as basically “an open secret,” according to Emily Tseffos, an Enough is Enough volunteer. “So many people have said, ‘Yeah, my child is in high school there and we know all about Coach Byrd,’ and it’s just something that because of the culture and because it’s a small place and he has a name, nobody’s doing anything about it,” she says.

Tseffos says one female voter claimed she knew of Byrd’s behavior, but that she had asked God for forgiveness, and that was all she felt she needed to do. She didn’t feel Byrd had committed any sin that couldn’t be absolved.

Both Rice and Cain echo this sentiment and say that now, and even when they were teens, Byrd’s alleged behavior was common knowledge. “The saying in our dressing room [was] ‘Byrd’s a perv, Byrd’s a perv,'” Cain recalls. “I mean, everywhere, everybody said it, whether you played ball or didn’t, ‘Byrd’s a perv.'”

Rice says she has been stunned by conversations she’s had with people who are either current or past employees of the local school district. She says one woman told her, “I don’t think that’s debatable, everyone knew he was doing that.”

Of course, this is not to say that everyone in the community feels comfortable with Byrd’s reputation. Tseffos says she had one conversation with a woman who used to work with Byrd at Wayne County High School. She said she had always heard the rumors, but no one ever did anything about it, and, as a Christian, she’s lost sleep over her own inaction. She was eager to vote against Byrd as a way of finally doing something.

Through the fall, Enough is Enough struggled to break through. Its work also sparked a backlash from some local conservatives, who tried to use the allegations as a Republican rallying cry. A PAC affiliated with state Rep. Casada, the House majority leader who was backing Byrd, ran attack ads about Enough is Enough, comparing Byrd to Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh (and President Donald Trump) and decrying the accusations as “lies and fake news” propagated by liberals.

Byrd won handily, and on election night, he posted on Facebook: “Thank you, District 71. I am honored and humbled by tonight’s results. I am very grateful and blessed for the opportunity to represent you on Capitol Hill.”

Tseffos feels Enough is Enough underestimated the culture of the rural area they were canvassing in—the particular problem being that Byrd’s behavior was already widely known in some capacity, and also that many people didn’t actually see his behavior as wrong. They talk about Byrd’s behavior as if it were a run-of-the-mill affair, despite the fact that the victims were minors who could not legally consent.

This attitude is evident in a recorded call between Rice and former Wayne County High School boys’ basketball coach Michael Edwards, who admits he knew Byrd molested Rice, though he appears to consider it consensual.

“I don’t care to tell you what he told me,” he says in the recording. “He said you all were in the office [at Wayne County High School]. You all started playing around a little bit. Said you all were trying to figure out somewhere to go, like to a hotel or motel or whatever, and then for some reason, I don’t remember what he said the reason was, you all backed out.”

When Mother Jones reached Edwards, he immediately said he had no comment. When asked why he didn’t report Byrd’s behavior, he said, “Report what?” Before I could reply, he quickly repeated that he had no comment, told me to “have a nice night,” and hung up.

Women in rural areas experience violence at a much higher rate than urban or suburban women. What’s often overlooked are the cultural factors that contribute to allowing abuse and ultimately protecting abusers. According to Walter Dekeseredy, who studies violence against rural women at West Virginia University, patriarchal structures remain firmly in place in many rural Southern communities, sometimes bolstered by evangelical belief systems that are at the heart of how these communities function. Often, they’re isolated to boot. Here, women are expected to be subservient to men, and masculinity in its most classic form is prized. It’s no surprise, then, that the #MeToo movement hasn’t gotten far in communities like this.

“People think that rural communities are these idyllic places where everyone’s nice to each other and they know they’re safe,” he says. “But really, we have conclusive evidence that the rates of violence against women are the highest in this country in rural areas. It’s not The Andy Griffith Show.”

That all likely contributed to an environment in which Byrd was afforded certain protections. Mother Jones also spoke with a local man who said his daughter played on the basketball team when Byrd was the coach. She told her father she felt she deserved more playing time, and he told her to take it up with Byrd. Months later, she told her mother she had gone to Byrd, who said if she wanted more court time, she would have to give him something in return. The father, who is remaining anonymous to protect his daughter’s privacy, said he confronted Byrd one night after a basketball game, and Byrd fled. He says he tried to take it up with the school’s administration, and he was told that they refused to “malign the reputation of David Byrd.”

“I feel bad, because I’m the one who told her to talk to the coach,” he says. “But I assumed he was an okay guy; I assumed this is cool, you know, the teacher is a coach, they have background checks. Well, I guess they don’t do that here.”

Dekeseredy says that in his case studies, he’s often found that men in rural areas who are the subjects of credible accusations of sexual misconduct are part of what he calls a “good old boys club”—members of a certain standing in the community, such as school administrators, who are dedicated to protecting their own.

For Rice, she says most people she’s talked to say they believe her—but they’re not necessarily calling for action. Some argue Byrd is not the same person he was 30 years ago. Rice also says her family has been treated poorly ever since she came forward; she’s still not comfortable going back to church.

Both Rice and Cain sometimes think about what might have happened had they reported Byrd back then. Cain had dreams of getting a basketball scholarship, but she says Byrd repeatedly told her the only way she could get a scholarship like that would be through him. “I believed him,” she says. “He put it in my mind that I was not good enough to get a college scholarship on my own.”

Rice thought about reporting Byrd, but she recalls him laying out the consequences for her: He would be fired, and she would be kicked off the basketball team and almost certainly kicked out of school. Nevertheless, she says, she kept waiting for someone to notice what was happening and ask her about it; no one ever did.

“The one thing I’ve learned, 30 years later,” Rice says, “is that if somebody would have [asked], it would have been the same doubt and the same ridicule that I’m getting right now.”

“I’m not doing this to try and ruin his name,” Cain adds. “I want him to admit that he did it.”