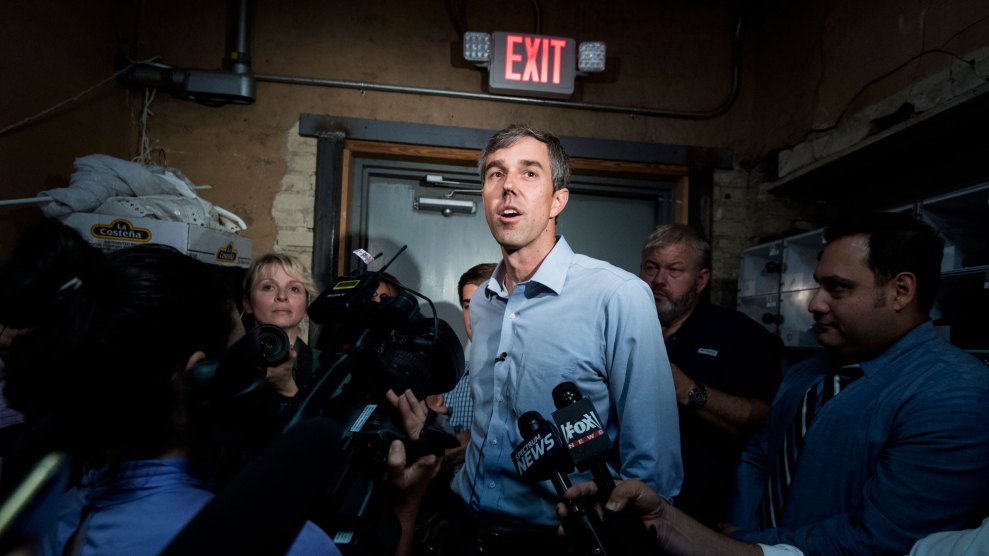

Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/AP Images

Republican attack ads during the Trump era tend to follow a familiar recipe: a splash of Colin Kaepernick, a dash of MS-13, and a whole lot of guns. But when Club for Growth Action aired its first ads attacking Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D-Texas) last month, the Republican-aligned super-PAC deviated from the formula. The 30-second spot, the first volley in an anticipated multimillion-dollar onslaught, focused on O’Rourke’s role in a controversial redevelopment plan in El Paso, where the Senate candidate served on the city council for six years starting in 2005. “Beto the Bully,” according to the ad, had used the threat of eminent domain to uproot a Mexican-American neighborhood on behalf of a “cabal” of wealthy “conquistadores”—such as his father-in-law:

Not long after that, O’Rourke’s Republican opponent, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, waded into the issue as well with a digital ad that featured old footage of angry community members confronting O’Rourke. Now, Club for Growth Action is out with yet another ad on the issue. In one of the year’s biggest Senate races, Republicans are focusing on the most local of issues. What’s this all about?

O’Rourke’s city council stint was defined by progressive battles that laid the foundation for his later campaigns for federal office. He faced a recall threat over an ordinance to extend domestic partnership benefits to same-sex couples, and he battled his own Democratic congressman over the War on Drugs. But the downtown plan has dogged him for years because of its dissonance with the political identity he’s embraced as a congressman. In this case, the candidate whose slogan is “people not PACs” joined ranks with some of the city’s most powerful businessmen on a project that drew vocal opposition in one of America’s poorest zip codes—the kind of marginalized community he has more often sought to champion. But the alliances he forged then also helped make his rise to higher office possible.

The redevelopment plan had its genesis in 2003, when a group of about 350 people, culled largely from the political and business elite of El Paso, formed an organization called the Paso Del Norte Group with the aim of revitalizing the city. Membership in the group cost as much as $1,800 a year, and its ranks included O’Rourke (who owned a small technology company and alternative newspaper) and several of his family members—most notably, his father-in-law, William Sanders, who had recently moved back to El Paso from Chicago after selling his construction company for $5.4 billion.

PDNG and its members had a variety of ideas about how to kickstart the city, which borders Juarez, Mexico, including a medical school that would serve the binational community. But foremost among them was turning the city center into a destination. As Steve Ortega, a former city councilman and good friend of O’Rourke’s told me last year, “we were a downtown that shut down after nine o’clock.” They believed there was “a mindset of acceptance of mediocrity,” Ortega said, that needed to broken by something ambitious. In February of 2005, three months before O’Rourke took his seat on the city council, the organization asked for, and received, $250,000 from the city to come up with a plan.

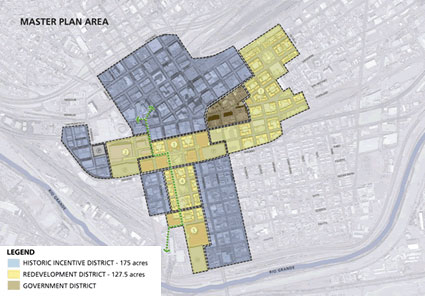

What PDNG revealed one year later, at a press conference at a historic downtown theater, was ambitious. It proposed to pump money into new developments in the area—an arena, shops and restaurants, big-box stores. It also called for the redevelopment of 128 acres—it would eventually grow to 168—of the historic Mexican-American neighborhoods Segundo Barrio and Duranguito, nestled in a bend of the Rio Grande adjoining downtown. The plan included processes by which current owners might relocate or sell on their own. But if property owners couldn’t agree on terms, the city had other tools at its disposal—including using eminent domain to claim properties that were designated as “blighted.”

A coalition of small businesses owners organized against the project. The Catholic Bishop expressed “deep concerns.” And a community group called Paso del Sur popped up to emphasize the heritage of the community. Its members held protests and crashed public meetings. “They were talking about tearing down a farmworkers’ center and using it as a parking lot for a Walmart,” says David Dorado Romo, an El Paso historian and co-founder of Paso del Sur.

O’Rourke, by now a city council member, drew the ire of activists not just because his father-in-law was leading the push or due to his own membership in PDNG, but because part of the area targeted for redevelopment was in his district. They were frustrated that O’Rourke, a member of the city’s Anglo elite, was deciding the fate of a place like Segundo Barrio. Their concerns were amplified, Romo says, by the city council’s approval of a study from an outside consulting firm to assess the city’s image.

Some of what the study found was fairly straightforward: El Paso lacked cachet outside the immediate region and lagged behind comparable Sun Belt cities. But one slide played to racist stereotypes, depicting a Mexican man in a cowboy hat next to the adjectives “gritty,” “dirty,” “lazy,” “speak Spanish,” and “uneducated.” To supporters like O’Rourke, stuff like this could be brushed aside for the sake of the broader point, but to opponents of the downtown project, it was the broader point. The community was being colonized by outsiders.

Critics of the plan attempted to organize a recall election and filed an ethics complaint against O’Rourke, alleging that even though he had no current financial stake in the development aspect of the project (his technology company had done some work for PDNG in the past), his work on the city council represented a conflict of interest because of his father-in-law’s role. (O’Rourke argued that his father-in-law’s role was irrelevant because Sanders had promised to give any profits from his investment to charity.) The recall organizers failed to turn in their signatures before the deadline. When the ethics complaint fizzled, O’Rourke told reporters he was the victim of “character assassination and political intimidation.”

“The slanderous accusation…that I am being or will be financially rewarded for my support of a plan to revitalize downtown El Paso—is ludicrous,” he said in a statement at the time. “But it doesn’t matter. Their hope is that should the smear be applied with enough force, ultimately a stain, on my honor and personal reputation, will take hold.”

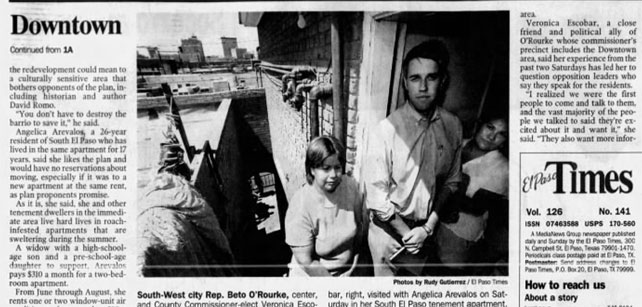

He weathered the storm in part by meeting it head on. Much like his current campaign, his strategy then placed an emphasis on visibility. O’Rourke and Veronica Escobar, a political ally who recently won the Democratic nomination for O’Rourke’s open House seat, went door-to-door in Segundo Barrio to make the case for the redevelopment plan to residents, and O’Rourke held a community meeting with his father-in-law at a South El Paso church. He took questions and answered in Spanish. A survey conducted by a community nonprofit found that a majority of residents who knew about the plan supported it. As the videos used in the recent attack ads show, the process was uncomfortable. But it was recognizably O’Rourke. When he was re-elected to the council in 2007, he won a narrow majority in the barrio itself.

Six weeks after the plan was unveiled, O’Rourke went door-to-door in the Segundo Barrio to make the case for redevelopment with a political ally, Veronica Escobar.

El Paso Times

He also adjusted his own position. The council scrapped the plan to tear down the farmworkers’ center. And after initially supporting the project’s calls for eminent domain, O’Rourke later voted with a majority of the council to put a one-year moratorium on its use. (The council extended the moratorium again the next year.) Although O’Rourke publicly rejected the idea that any conflict existed, he acquiesced to the demands of opponents and recused himself from many of the city council actions directly related to the project. But he didn’t step aside on every vote that might affect it. When opponents attempted to change city blight laws to make it harder to condemn whole neighborhoods, O’Rourke cast a deciding vote against it.

In the end, eminent domain was never used, and the project was never fully adopted as planned. Texas voters passed a constitutional amendment limiting the use of eminent domain in 2009—a majority of El Pasoans voted for it. Paso del Sur activists are still fighting; a legal challenge to block construction of an arena in Duranguito is currently tied up in the courts. But that plan was only greenlighted by the city council in 2012, after O’Rourke had already left. The city changed anyway. “It’s quite simply a different place than it was 10 years ago,” boasts Ortega, the former city councilman. Downtown is home to new hotels and restaurants, and the Triple-A Chihuahuas now play in a new stadium not far from the international bridge linking El Paso to Juarez.

But that doesn’t mean eminent domain didn’t have an impact in El Paso. Residents weighing whether to stay or to sell had to think about whether they’d always have a choice. “They used eminent domain—they used it as a threat,” Romo says.

The story doesn’t end there, though. To O’Rourke’s critics, the saga also undercuts his image as a champion of small-dollar donations. O’Rourke put a self-imposed cap on individual donations at $250 during his 2007 re-election campaign, which he described at the time as a “referendum” on the downtown plan. But in racking up a 10-to-1 cash advantage over his opponent, he brought in checks from a number of individuals who were involved in the development plan, including some prominent Republicans. Woody Hunt, a billionaire construction magnate and Republican megadonor who was an active PDNG member, co-hosted a fundraiser for O’Rourke. When O’Rourke launched his primary challenge to incumbent Rep. Silvestre Reyes in 2012, many of those same donors anted up again.

Dozens of PDNG members, including some Republicans, maxed out to his campaign, and a handful of other individuals or businesses involved in the plan—including a company owned by his father-in-law—donated to a super-PAC called the Campaign for Primary Accountability, which ended up spending $240,000 against Reyes.

Reyes ran ads highlighting the eminent domain push, but to no avail.

O’Rourke’s victory over Reyes—he avoided a runoff by 216 votes—owed a lot to his tireless campaigning and fresh critique of the Drug War at a time when the violence in Juarez was near its peak. But money from Republicans and developers, many of whom were part of the Paso Del Norte Group, funded O’Rourke’s campaign to an unusual degree, and Republican voters helped push him over the top in the primary. The El Paso Times reported that more than 700 Republicans who had voted in three consecutive Republican primaries voted in the Democratic primary that year instead.

But to the activists who hounded O’Rourke all those years, there is something a little off about Cruz and his Republican allies co-opting an attack about gentrification, because Republican politicians in Texas have never demonstrated an excess of compassion for the working-class Mexican-Americans who call places like Segundo Barrio home. Cruz has been to El Paso, the state’s sixth-largest city, just four times since being elected six years ago. His platform, like the president’s, calls for militarization of the border and a crackdown on undocumented Texans—a one-two punch for a bi-national community on the Rio Grande.

As it happens, the sometimes-shaky footage that anchored Cruz’s attack ad was originally posted on YouTube by Romo, the El Paso historian. When we spoke, he told me he had met with a lawyer to discuss the possibility of a lawsuit against Cruz’s campaign, though no further action has been taken. “In no way do I want Cruz to exploit our own work for his utterly nefarious politics,” Romo says.

He adds, “I think some of the things that O’Rourke has done are reprehensible—but anybody from Texas running would be 100 times better than Cruz.”

In response to a request for comment, the O’Rourke campaign sent a link to an El Paso Times story in which Stuart Blaugrund, the attorney who lodged the ethics complaint against O’Rourke a decade ago, called Cruz’s attack “misleading” and said that in the end, O’Rourke “did the right thing” by recusing himself from most matters related to the project.

Some of the same donors O’Rourke came under fire for working with are Cruz supporters. Last year, Hunt donated the maximum amount ($2,700) to Cruz’s general election campaign, and he cut another $5,000 check to the senator’s Jobs, Freedom, and Security PAC. In other words, the ads villainizing the development plan were funded in part by one of its architects. Hunt has also given about $231,000 this cycle to the National Republican Senatorial Committee, which is reportedly weighing an ad blitz on behalf of Cruz.

But Cruz’s discomfort with eminent domain is also less than sincere. Both he and the Club for Growth Action attacked President Donald Trump over the issue two years ago, only to cozy up to him shortly thereafter. And Cruz has backed the government seizure of private property when it comes to pipelines and border walls. When the candidates’ first debate rolled around last month, it was O’Rourke, not Cruz, who raised the specter of eminent domain.

“That wall will not be built on the international border between the United States and Mexico,” he said. “It’ll be built on someone’s farm, someone’s ranch, someone’s property, someone’s homestead.”