Voters wait in line for ballots at the Polk County Election office on the first day of early voting for the Iowa general election on October 8 in Des Moines. Charlie Neibergall/AP

Deidre DeJear announced her candidacy for Iowa secretary of state last August, on the 52nd anniversary of the signing of the Voting Rights Act. It was a fitting date: DeJear, 32, was born in Mississippi, where her grandparents were not able to vote before the Voting Rights Act, and now she was trying to become the first African American to win a statewide election in Iowa history. She was also trying to reshape voting rights in the state: Her opponent, incumbent Paul Pate, had authored a voter ID law passed by Iowa’s Republican state Legislature in 2017 that threatened to disenfranchise thousands of eligible voters. It was a prime example of how Republican secretaries of state have used their office to restrict access to the ballot, and how Democratic challengers are now seeking to fight back.

“Voting rights is key in this office,” DeJear said in an interview in her campaign office near downtown Des Moines, which she shares with the voting rights group Let America Vote. “Our state is held accountable to the national Voting Rights Act, our state is held accountable to the National Voter Registration Act, and we need a secretary of state that is adhering to those guidelines and making sure we’re getting as many people as possible registered and participating in the voting process.”

Republican secretaries of state like Pate, Kris Kobach in Kansas, Brian Kemp in Georgia, and Jon Husted in Ohio have led their party’s efforts to make it harder to vote, through aggressive voter purges, strict ID laws, and new barriers to voter registration. Though secretaries of state do not pass election laws, they design and implement them as the top state election officials. They decide how registration lists are maintained, where polling places are located, and how voting machines are secured. The recent furor in Georgia over Kemp’s blocking of 53,000 voter registration applications—80 percent from people of color—at the same time he’s running for governor has shined a spotlight on the importance of this once-obscure office.

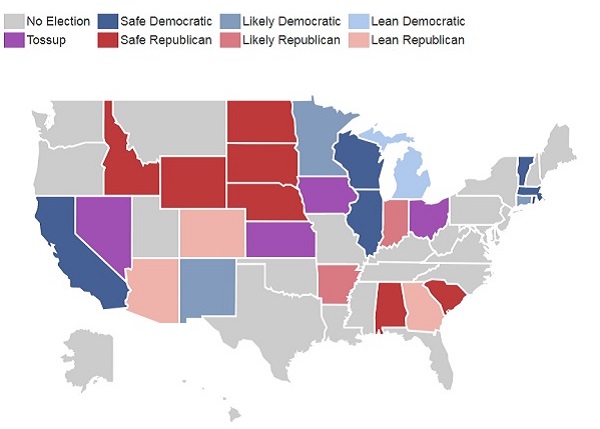

Republicans currently control 29 secretary of state offices, compared to 17 for Democrats. (Pennsylvania has a nonpartisan secretary of state, and three states don’t have the office.) But a new crop of Democratic candidates like DeJear could pick up at least half a dozen secretary of state seats in 2018 in key swing states such as Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, and Ohio. Governing magazine lists eight of the 26 secretary of state races this year as toss-ups, and says six of them have shifted in the Democrats’ favor since June. These Democratic candidates are running on platforms that would expand voting rights, and their victories would give Democrats the power to shape voting laws in critical states that could determine the outcome of the 2020 presidential election and the round of redistricting that will follow.

The office gained national prominence during the 2000 election, when Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris, a state co-chair of the Bush-Cheney campaign, halted her state’s recount to elect George W. Bush. Four years later, Ohio Secretary of State Ken Blackwell, who co-chaired the Bush-Cheney reelection campaign in the state, issued a series of directives limiting the availability of provisional ballots and blocking voter registration applications. Blackwell oversaw an election in Ohio, the state that tipped the contest to Bush, in which voters in Democratic strongholds like Columbus waited five hours to vote because polling locations in urban areas didn’t have enough voting machines. “Two Republican secretaries of state decided two presidential elections,” says Ellen Kurz, who founded the advocacy group iVote in 2014 to elect Democratic secretaries of state who support voting rights. The secretary of state position took on added significance when politicians like Kobach, Kemp, and Husted were elected in 2010 and used their offices to lead a nationwide movement to restrict voting rights, while spreading unfounded fears of widespread voter fraud.

Iowa is an unlikely battleground in the country’s voting wars. It has some of the most progressive voting laws of any state: It allows Election Day registration, and ranks near the top in voter turnout. But DeJear threw her hat in the ring after Pate lobbied the Iowa Legislature to pass a voter ID law last year that could prevent the 11 percent of Iowans—260,000 eligible voters—who don’t have a driver’s license or state photo ID card from voting. “My biggest concern is that people are very unaware about it,” DeJear says. “The secretary of state did not provide our county auditors with the proper training for this specific law. In the primary, a lot of folks were confused about our voting laws.”

Under the new law, voters without an ID can still cast a ballot by signing an oath attesting to their identity, but that fallback provision will end after the 2018 election. During Iowa’s primaries in June, nearly 2,000 voters did not show the required photo ID in the state’s 10 largest counties, accounting for almost 1 percent of the electorate. The law also required voters using absentee ballots to supply an ID number, and allowed poll workers to reject absentee ballots when a voter’s signature didn’t match the signature on other state records; a state court temporarily blocked those provisions, but they could take effect next year pending a full trial. The judge chided Pate for telling voters ID was required to vote in 2018, writing that the law and the secretary of state’s actions “substantially and directly interfere with Iowans’ constitutional rights to vote.”

There’s little evidence of in-person voter fraud in Iowa, and the only Iowan convicted for illegal voting in 2016 was a Donald Trump supporter who voted twice because she believed Trump’s claims the election would be rigged. Pate has admitted “we’ve not experienced widespread voter fraud in Iowa,” but he also released misleading statistics to the press over objections from his staff that made fraud seem more prevalent than it is.

In contrast to Pate, DeJear, a self-described “voting nerd,” wants to expand the electorate by implementing policies like automatic voter registration. She moved to Iowa to attend Drake University in Des Moines, then worked as head of African American outreach for Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign there. Obama’s reelection effort registered 5,000 new black voters in one of the whitest states in the country, and African Americans made up 7 percent of Iowa’s electorate in 2012, compared to 3 percent in 2008. DeJear sees that campaign as a template for increasing voter participation. “It’s my goal to make sure we have increased turnout in this election,” she says. Governing lists the race as a tossup.

Folks, I'm running for Iowa Secretary of State and I think it's important that you know why. Here's a taste. More to come. #DeJearForIowa pic.twitter.com/XlYg1GsPU3

— Deidre DeJear (@DeidreDeJear) August 28, 2017

Other Democratic secretary of state candidates have already spent time fighting in the voting rights trenches. In Ohio, state Rep. Kathleen Clyde is running to replace Jon Husted, who purged 2 million voters from the rolls from 2011 to 2016, more than any other secretary of state. Black voters in the state’s largest counties were twice as likely as white voters to be removed from the rolls. Clyde, who represents the city of Kent in northeast Ohio, led opposition to voter purging in the state Legislature and has sponsored legislation to protect the voter rolls. She has also authored legislation to use paper ballots in order to prevent election hacking, and has fought to reverse the Ohio Legislature’s repeal of the first week of early voting, when black voters were five times more likely than whites to cast a ballot. “In Ohio, there is a lot of power to fix a pretty broken system,” Clyde told me. “Ohio decides presidents, and it is important that we have a fair election in our state in 2020.” (Her opponent, Frank LaRose, who like Clyde joined the state Legislature in 2011, sponsored the voting restrictions she wants to reverse.)

For me, it’s not about Republican ideas or Democrat ideas, it’s about good ideas. That’s what I learned growing up in my small town, what I’ve brought to the Statehouse and what I’ll bring to the office every day as Ohio’s next Secretary of State. pic.twitter.com/4M7q3qs4VJ

— Kathleen Clyde (@KathleenClyde) October 11, 2018

In Michigan, Democratic candidate Jocelyn Benson literally wrote the book on secretaries of state, called State Secretaries of State: Guardians of the Democratic Process. At 36, Benson was named dean of Wayne State Law School in Detroit, becoming the youngest woman ever to lead an accredited law school. She ran unsuccessfully for secretary of state in 2010. But in 2018, she says, “It’s night and day. There’s more attention to secretaries of state races than ever before.” Because of the twin threats of Russian hacking and voter suppression, “there’s an increased recognition of the role that secretaries of state play,” she says.

Benson’s signature proposal is that no one in the state should wait longer than 30 minutes to vote. Michigan has some of the least voter-friendly election laws in the country, but there are initiatives on the 2018 ballot to enact automatic and Election Day registration, along with nonpartisan redistricting—ideas Benson has long championed. “This election in Michigan is one that will define our democracy in the state for years to come,” she says. Her Republican opponent, Mary Treder Lang, opposes the ballot measures. Treder Lang credited voter purging by Michigan’s outgoing Republican secretary of state, Ruth Johnson, for Trump’s 10,000-vote victory over Hillary Clinton in Michigan in 2016, saying, “If Ruth Johnson did not remove her half a million individuals, dead people from our voter files, before the 2016 election, this state here would not be red, nor would we have President Trump in our office today.”

Have you seen it yet? Our new ad hit the air yesterday! Check it out, let me know what you think, and chip in today to help us keep it on the air: https://t.co/ouA3TiThCS pic.twitter.com/MEo4KX6ccU

— Jocelyn Benson (@JocelynBenson) October 10, 2018

In Georgia—the current epicenter of the voter suppression battle—former Rep. John Barrow, the last white Democrat from the Deep South in the House of Representatives, is running to succeed Kemp. Barrow has criticized Kemp’s voter registration policies as “plainly illegal” and has been an outspoken opponent of gerrymandering after Georgia Republicans redrew his district to oust him from Congress in 2014. Barrow called the secretary of state’s office “possibly the most important job nobody knows anything about.”

Despite the increased attention to these races, they are still overshadowed by higher-profile gubernatorial and congressional contests. In 2014, nearly 37,000 Iowans voted for governor but not secretary of state; Pate won his election by 20,000 votes. “We still need a lot more attention to how important these offices are and how they’ve used it for Republican gains,” says iVote’s Kurz.

The secretary of state races come amid a broader push by Democrats to reverse Republican suppression efforts. There are ballot initiatives in seven states, including Florida and Michigan, that would restore voting rights to ex-felons, make it easier to register to vote, and crack down on gerrymandering. If these initiatives pass and Democratic candidates like DeJear, Clyde, Benson, and Barrow are elected, the landscape for voting rights will look very different in 2020.