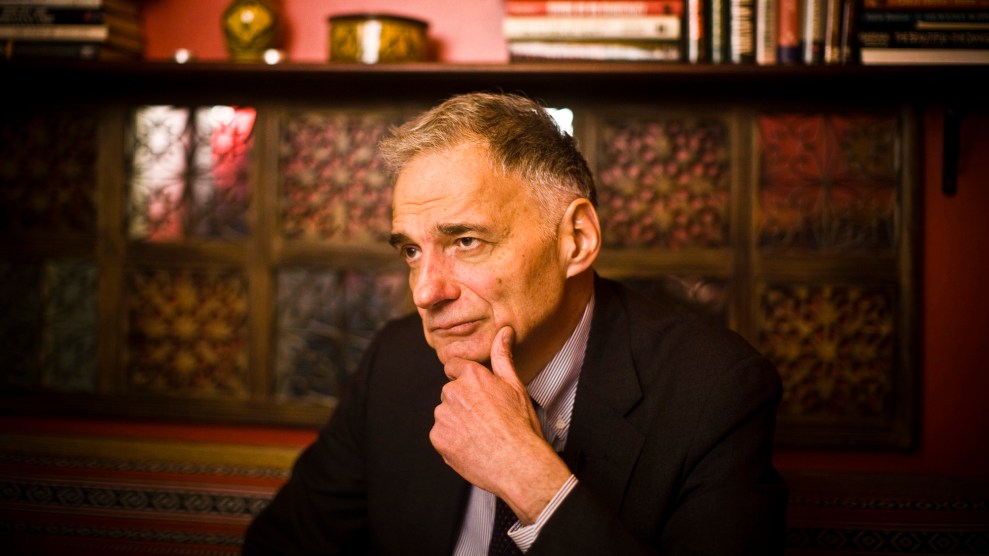

Brett Kavanaugh on the first day of his confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee on September 5Christy Bowe/ZUMA

On Thursday, Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh will testify under oath that the charges of sexual misconduct against him are “false and uncorroborated.” That’s according to his prepared statement, which was posted online Wednesday by the Senate Judiciary Committee. “Eleven days ago, Dr. Ford publicly accused me of committing a serious wrong more than 36 years ago when we were both in high school,” he will state, adding, “Over the past few days, other false and uncorroborated accusations have been aired.”

For someone applying for the top legal job in the country, this statement is ambiguous at best and incorrect at worst. Legally speaking, the allegation by Christine Blasey Ford of an assault in the early 1980s is corroborated, as are later claims by Deborah Ramirez, who has alleged a second assault in which Kavanaugh thrust his penis in her face during a dorm room party when they were both attending Yale University.

It’s unclear—perhaps purposefully so—whether Kavanaugh’s statement applies to Ford as well as Ramirez. It may also be intended to include Julie Swetnick, who came forward Wednesday morning with allegations of sexual assault in the 1980s. But Ford and Ramirez’s allegations both come with what attorneys typically call corroboration. “To call these allegations uncorroborated, is wrong, since contemporaneous statements of a victim are one of the best guarantees of truthfulness,” Joyce Vance, a former US attorney in Alabama, told Mother Jones in an email. Ford, she noted, told people, including her therapist, about the assault years before Kavanaugh was nominated to the Supreme Court.

Corroboration does not have to prove guilt or innocence beyond a reasonable doubt. “Some corroborative evidence is very good, while other is of lesser quality,” Vance wrote. “It can even be the case that multiple pieces of information, that in and of themselves would not suffice, can form more solid corroboration when taken as a whole.”

Laurie Levenson, an expert in criminal law and evidence at Loyola Law School, also said Kavanaugh’s use of the term “uncorroborated” was incorrect as a legal term. Accounts by Ramirez’s Yale classmates that they had heard about her attack decades ago, and even statements about Kavanaugh’s general behavior when drinking while in college, are all forms of corroboration. “I think words are being used now just for political purposes and not at all how we would legally use those terms,” she said.