Mother Jones Illustration

Less than three hours remained in Connecticut’s legislative session, and chaos was unfolding at the state capitol building in Hartford. Lobbyists lined the hallways, clamoring to learn whether their bills had survived the night. Legislative aides, tucked away in a maze of offices, sipped beers as they hurried through the session’s remaining administrative tasks. In the House and Senate chambers, lawmakers hustled to cast votes in rapid-fire succession, creating a racket that echoed up to the packed galleries.

Making his way through the mayhem was a man who had no legislative business that night: It was Democratic gubernatorial candidate Ned Lamont, carrying two trays of blue-iced, donkey-shaped sugar cookies. The baked goods were a gesture of goodwill for exhausted legislators. It’s something of a tradition in Hartford—every four years, would-be governors hit the Capitol’s white marbled floors at the close of the session, glad-handing with captive lawmakers who, in the coming weeks, would endorse candidates in the primary and general elections. Lamont, looking the part in a navy suit and matching striped tie, wound his way through the crowd, lingering with his party’s heavy hitters as he delivered his treats to the House and Senate floor.

If Lamont’s name sounds familiar, it should. Twelve years ago, the then-52-year-old businessman captivated progressives across the country with his primary campaign against three-term Sen. Joe Lieberman, who, among other things, had been the party’s 2000 vice presidential nominee. By 2006, Lieberman had angered liberals with his unwavering support of the increasingly unpopular Iraq War—though he still had the backing of much of the Democratic establishment. The race was heralded in the press as “a fight for the party’s soul” and a bellwether for the future of the Democratic politics.

Lamont was calling for radical change, and he put his opposition to the war at the center of his campaign. “Stay the course: That’s not a winning strategy in Iraq, and it’s not a winning strategy for America,” he said at the time.

Lamont won a narrow victory in the primary, but Lieberman then ran as an independent in the general election and defeated him. In recent weeks, the 2006 race has drawn comparisons to Democratic Socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s stunning primary win over Rep. Joe Crowley, a member of the House Democratic leadership team. Lieberman even encouraged Crowley to wage a third-party campaign in November, a suggestion that Crowley has so far rejected.

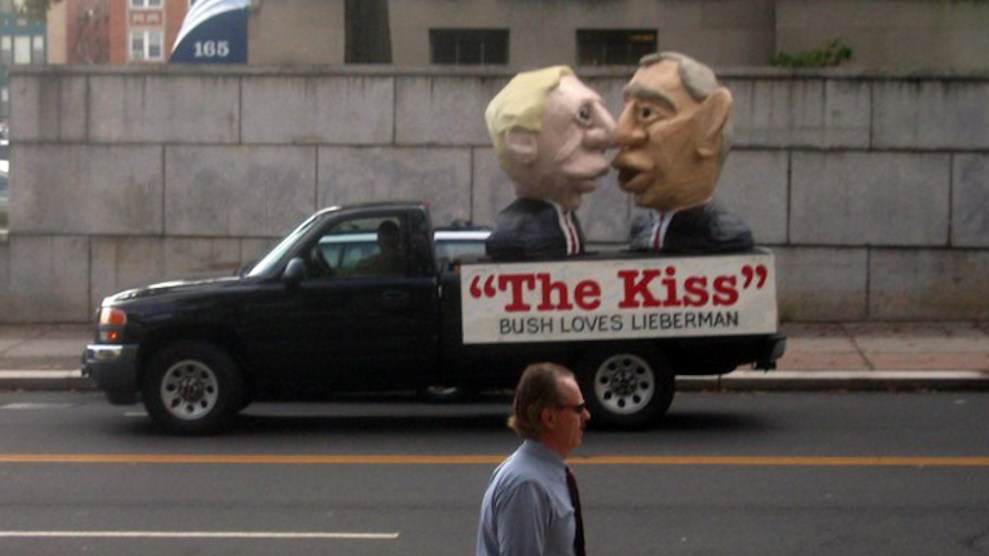

It’s 2018, and Lamont, now 64, is back—but “progressive” looks a little different on him than it did in 2006. So do the problems in the state he’s seeking to lead. Should Lamont prevail in his latest bid for statewide office, he’ll take the reins of an economically stagnant state whose current Democratic governor has rock-bottom approval ratings. Now, the one-time anti-war firebrand touts a decidedly technocratic platform focused on improving Connecticut’s fiscal prospects. Gone are the armies of bloggers and the larger-than-life parade float depicting Lieberman kissing President George W. Bush. What remains, however, is Lamont’s willingness to wade into hazardous political waters and take on a challenge no one else seems to want.

Lamont delivers cookies to Connecticut legislators on May 9, 2018.

Kara Voght/Mother Jones

Sixteen states are holding contests for open gubernatorial seats this year, and those races typically draw a crowded field of candidates. Not so among Connecticut Democrats. The incumbent, Democratic Gov. Dan Malloy, has opted not to seek a third term. Finding a viable Dem to replace him was nothing short of political hot potato—no one wanted to be left holding the legacy of one of the nation’s least popular governors. The obvious contenders, such as Lt. Gov. Nancy Wyman, Attorney General George Jepsen, Comptroller Kevin Lembo, and state Sen. Ted Kennedy Jr.—son of the late Massachusetts senator—all quickly bowed out.

Despite Democratic dominance in the state’s presidential and congressional elections and a national political environment that has liberals giddy about a possible blue wave, the race for governor is different. The Cook Political Report rates the contest a “toss-up,” and an April poll suggested the Republican candidate would start the race with a wide lead.

Nutmeggers haven’t sent back-to-back Democrats to the governor’s mansion in more than three decades, but that’s not the only reason Dems were reluctant to run. Connecticut boasts a long, nightmarish list of undesirable superlatives, and after eight years in power, Democrats are getting much of the blame. Among all states, Connecticut has lately ranked first in state debt per capita, fourth in population loss, and 46th in job growth. Major employers, such as General Electric and Aetna, have been fleeing the state for its more attractive urban neighbors, Boston and Manhattan. Malloy spent much of his second term mired in a budget crisis, and whoever succeeds him will contend with a $2 billion funding deficit during their first year in office.

“It’s not going to be fun,” Denise Merrill, Connecticut’s Democratic secretary of state, says of the governor’s race. “And part of it is combating the perception that Connecticut is terrible.”

Fun or not, Lamont’s interest in running for elected office has long been clear. After challenging Lieberman in 2006, he lost a gubernatorial primary to Malloy in 2010. He’s been sitting on the sidelines for the last eight years, “watching this state go sideways,” he says. “Being governor is a job where you can make an extraordinary difference,” he adds. “I’ve been storing up for quite some time.”

Still, Lamont took some convincing this time around. He entered the race in January at the urging of George Jepsen—the state’s retiring attorney general and Lamont’s longtime friend and adviser—and Sen. Chris Murphy, who’s taken a leadership role in the state’s Democratic politics during his 2018 reelection campaign. Jepsen recalls months of back-and-forth as Lamont weighed his candidacy. “He’d call me up and say, ‘We can’t talk you into running for governor?’” Jepsen says. “No!” Jepsen would reply. “Why don’t you run for governor?”

Lamont only jumped into the contest “when people he would have liked to have seen run did not,” says Jepsen. That’s a through-line that goes all the way back to the 2006 Senate campaign, a race Lamont entered under similar circumstances. “I was a former selectman who was just mad as hell at what was going on in our political system,” he recalls. “I couldn’t get anyone else to run, so I pulled into it.”

Jepsen reads Lamont’s professed reluctance as a sign of personal integrity. “As the Iraq War situation shows, he’s willing to step up and do and say the right thing,” Jepsen says. “One of the things I like about him running for governor is that I think Ned would do what’s right to get Connecticut on track, even if it means he’s just a one-term governor.”

Lamont’s willingness to “do and say the right thing” in his challenge to Lieberman was met with a flood of support from progressives—especially opponents of the Iraq War. “Lamont showed a lot of courage,” says Matt Stoller, a prominent blogger at the time and now a fellow at the Open Markets Institute. “He was a symbol for somebody who was willing to stop the war.”

Support for Lamont in 2006 extended beyond the borders of Connecticut, as progressive bloggers like Stoller drew national attention to his underdog run, raising money and organizing volunteers. “Dozens of liberal and antiwar bloggers, some of them from across the country but many others in Connecticut, have rallied to Mr. Lamont’s cause,” noted a 2006 New York Times article describing the phenomenon. “They file daily posts attacking, investigating or just tweaking Mr. Lieberman while spreading a pro-Lamont message.”

Mother Jones also covered the 2006 race extensively, documenting a man whose “name recognition was once close to nil” when the campaign began, but who ascended to prominence through “strong netroots support…to the point where even Vice President Dick Cheney has singled him out for attack.” I asked Lamont if he remembered our reporting. “I’m afraid I do, and I say ‘afraid’ because I haven’t read you since,” he said. “But I will! How are you guys doing? Is Trump great for Mother Jones? You guys were great in that Lieberman campaign—one of the first guys to start following what was going on.”

The progressive energy wasn’t enough to bring down Lieberman, who held onto his seat largely by capturing big majorities of Republican and independent voters in the general election. But Lamont’s primary win was the leading edge of an anti-war wave that year that toppled two of the state’s three Republican members of Congress, kicking off the federal careers of Murphy and Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) and giving Democrats full control of Congress for the first time in 12 years.

Lamont’s hold over Connecticut Democrats was short-lived. A number of 2006 Lamont voters I spoke with abandoned him during his gubernatorial campaign four years later and backed Malloy instead. That included Jepsen, who served as chair of Lamont’s 2006 campaign. Many saw Malloy’s 14 years of experience as mayor of Stamford, one of Connecticut’s biggest cities, as more compelling than Lamont’s single term as selectman of Greenwich and his handful of years serving on the town finance board.

Voters also sensed a shift in rhetoric, and they didn’t like it. Lamont’s anti-war brand bore little relevance to the job description of the state’s top executive, and the business-friendly agenda he adopted was met with a lukewarm reception. His silver-spooned background also created some dissonance with the liberal base: Educated at Phillips Exeter, Harvard, and Yale, Lamont is also the great-grandson of a former J.P. Morgan chairman. He’s poured millions of dollars of his own money into his campaigns—wealth acquired from his cable business, which he sold in 2015 for an undisclosed sum. “Progressives are grumbling that he has talked too much about tax breaks and streamlining red tape, and not enough about issues dear to labor unions and government watchdogs,” noted the New York Times in 2010.

“When I took on Dan eight years ago, I was this business guy from Greenwich—what would labor want with me?” Lamont says. “It was a pretty tough sell. But now, I know the state, and the state knows me, in a very different way.”

Indeed, Lamont spent the last eight years trying to bridge that divide. He took on adjunct teaching responsibilities at a local university, where he created a student start-up competition and worked with representatives of Connecticut’s business, nonprofit, and labor sectors on a plan to bring new jobs to the state. Earlier this year, he brought that experience out of the classroom and into a public-private partnership with Malloy and Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin that lured India-based IT giant Infosys to Hartford, a move expected to provide 1,000 much-needed jobs to the state’s struggling capital city.

“No, no, no, that’s not true at all!” Lamont protests when I mention that oft-cited 1,000-job statistic. “They will train 500 to 1,000 people per year in IT skills. That’s what nobody understands. Everybody thinks Infosys is a computer company with 1,000 jobs.” He explains that, in addition to Infosys’ own labor needs, the company plans to partner with local employers and train their workers, “so places like Aetna and Cigna can upgrade their workforce rather than leave the state.”

Lamont’s a details guy, which creates headaches for staffers charged with keeping him on a schedule. He spends campaign events diving deep into the weeds with voters—Jepsen calls him a “genuine policy wonk,” and others who know him well say it’s a defining personality trait. But just as significant, allies say, is his optimism—a quality that could be invaluable for a candidate hoping to govern a state as messed up as Connecticut. “He’s a real kind of positive force, and I honestly think that’s the kind of thing Connecticut needs right now,” Merrill says.

Lamont’s home-state boosterism extended to our interview. When I—a 28-year-old Willington, Connecticut, native—told him I felt like I couldn’t come back to the state because of the economic situation, he grew indignant. “What do you mean you couldn’t come back?” he shrieked. “You could be Mother Jones‘ Connecticut correspondent! You could start a business! You could hang out in New Haven if Willington was a little slow on a Thursday night! You could do a lot of shit!”

But for all his protest, he empathized. Lamont’s three children are around my age, and he knows the state is much less hospitable to young adults than it was when he and his wife, Ann, a successful managing partner at a venture capital firm, began their careers there four decades ago. “When Annie and I moved to Connecticut in our 20s, we’d thought we hit the jackpot,” he recounts. “Now, our kids are in their 20s, and they’re all in New York.”

Lamont accepts the endorsement for governor at the state Democratic convention on May 19, 2018.

Jessica Hill/AP

And so his gubernatorial pitch focuses on economic growth. He wants to nurture the state’s cities and attract new employers. He’s also promising to upgrade the state’s rail system, with hopes of transforming the now-hours-long slogs to Boston and New York into palatable daily commutes. “And then, all of a sudden, New Haven would be an amazing alternative to New York, at one-half the price,” he explains.

He’s put paid medical and family leave high on his agenda, citing policies from the most successful companies, like Disney and Google. “I can sell this not just as a pro-family idea, but a pro-business idea,” he says. “If I can brand the state as a place that understands what a 21st-century family is going through, maybe, just maybe, some businesses and young people will start coming here.”

Instead of alienating Democrats like in 2010, Lamont’s message seems to be resonating. Those who attended a “Meet the Candidate” gathering at a bar outside Hartford used adjectives like “practical” and “pragmatic” to describe him. Michael Daly, the chair of the Democratic Town Committee in Farmington, sees Lamont’s new approach as a strategic move that could put him over the top. Daly even compares 2018 Lamont to 2006 Lieberman. “The left decided that Lieberman was pro-war, but he won because he understood where the state was at,” Daly says. “I think Ned understands that now. I really do.”

But Lamont has some hurdles to clear before he can take his vision to Hartford. Though he emerged as the consensus candidate early on, he faces a primary challenge from Joe Ganim, the mayor of Bridgeport, who served seven years in prison on corruption charges. That black mark might bar some from seeking higher office, but Ganim has a loyal base that delivered more than twice the number of signatures required to appear on the primary ballot, and those devotees find his years of public service more compelling than Lamont’s parachute act. Lamont “talks a good game, he loses the election, he disappears,” says Ezequiel Santiago, a state representative from Bridgeport, who backed Ganim at the state Democratic convention. “All of a sudden he pops out of nowhere with big money. My question is, ‘Where have you been, and what is your plan?’”

And Lamont has taken some early steps that could alienate key Democratic constituencies. He chose Susan Bysiewicz—a former secretary of state, Senate candidate, and polarizing figure within the state party—as his running mate. In doing so, he snubbed Eva Bermudez Zimmerman, a young Latina activist and union organizer who would have brought youth and diversity to a ticket that otherwise plays like a rerun of nearly every Connecticut election in recent memory.

Republicans, meanwhile, have a large field of contenders who smell blood in the water, and whoever emerges from the August 14 primary could pose a formidable challenge to the Democratic nominee. The front-runner, endorsed by the state GOP, is Mark Boughton. He boasts nine terms as the mayor of liberal, immigrant-rich Danbury and is also running on a business-friendly platform of the conservative sort, pledging to slash the state income tax and eliminate fees on businesses. He’s joined in the Republican primary by Tim Herbst, a former first selectman from the city of Trumbull, who has embraced President Donald Trump’s style, and by three businessmen who, like Lamont, hail from the state’s wealthy, Metro North-adjacent communities.

As in any election, it will likely come down to who turns out—whether anti-Trump fervor can overcome local Democratic malaise. Lamont is hoping he can channel some of the ’06 progressive passion once more. “It was the biggest turnout we’ve had in Democratic primaries, before or since,” he says. “It’s what I tell these folks—stay true to what you believe, and people turn out.”

Connecticut capitol photo: Wikipedia; Lamont Uncle Sam photo: Keelin Daly/The Greenwich Time/AP