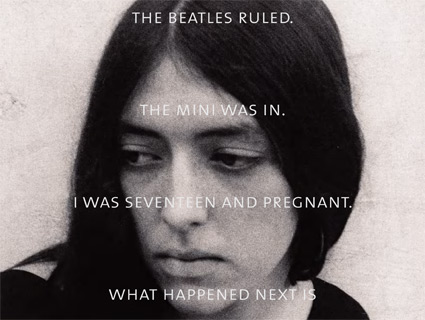

Kolbert outside the Supreme Court after arguing Planned Parenthood v. Casey.CSPAN

In the weeks since Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement from the Supreme Court, Americans who support abortion rights have sounded the alarm about the dire consequences if Trump’s nominee—announced Monday as Judge Brett Kavanaugh—joins the court. The staunchly conservative Kavanaugh’s confirmation would mean a court makeup that, for the first time in decades, includes a majority of justices who may be willing to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 case that legalized abortion.

For attorney Kathryn Kolbert, the historic moment is familiar. Kolbert, now retired and 66 years old, is best known for arguing a different landmark Supreme Court abortion case, 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Kolbert, then working with the American Civil Liberties Union, was charged with convincing that era’s conservative majority—newly-formed after Justice Clarence Thomas replaced liberal Justice Thurgood Marshall—as it was presented with its first opportunity to overturn Roe. In Casey, Kolbert challenged five Pennsylvania abortion restrictions. Several banned abortions under certain circumstances, a direct challenge of the fundamental right to choose enshrined in Roe.

No one thought Kolbert would win the case—including the attorney herself. “We fully believed we were going to lose,” Kolbert recalls. “The court was not only going to overturn Roe, but essentially create a standard that allowed states to recriminalize abortion.”

And they would have—were it not for a dramatic, last minute change of heart by Justice Kennedy, widely rumored for decades, and later confirmed in the public papers of Justice Harry Blackmun. The result was a major abortion rights victory: While Roe is the case that created the right to abortion, Casey became a key piece of the legal framework affirming that right.

Kolbert spoke to Mother Jones about the turn of events that forever changed abortion rights in America, about building a winning strategy for a losing case, and about her advice for attorneys now gearing up to preserve Roe.

Mother Jones: Tell me about the significance of Casey to the legal landscape of abortion rights.

Kathryn Kolbert: In 1992, after the appointment of Justice Thomas to the Supreme Court, experts widely believed the court had five votes willing to overturn Roe. The first case to get to the high court following the ascension of Justice Thomas was Casey. We all believed at that time that there were five votes and that the court was not only going to overturn Roe, but essentially create a standard that allowed states to recriminalize abortion.

Following my oral argument in Casey, Justice Rehnquist wrote an opinion that overturned Roe. Fortunately, Justice Kennedy switched his vote at the last minute and the court issued what we now know as Planned Parenthood v. Casey, that enabled states to place greater restrictions on the right to choose abortion but upheld the hallmark of Roe—that states couldn’t criminalize the procedure, and that legal abortion remained permissible. It was a big win for the pro-choice movement given what we thought was going to happen.

MJ: Casey lowering the standard of review for abortion laws also set up the foundation for a big push around passing new abortion restrictions.

KK: Yes, although those who oppose abortion have been pushing restrictions on abortion since 1974, the year following Roe. The people who have been most hurt by those restrictions have been young women, poor women, disabled women, rural women, women who have less political power. But in the years following Casey, ’92 to probably ’98 or ’99, there were actually fewer restrictions. But there’s been a raft of them ever since, the worst having come in the last eight years. Since 2010, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in state legislative efforts to impose restrictions. That’s because the Republicans control many, many more governors seats and state legislatures.

MJ: When you approached this case, you knew that overturning Roe was very much on the table. What was your strategy?

KK: Our strategy was to set up an opportunity to win back the right the court would take away—either in Congress or in state legislatures. To make sure people in the country understood what was at stake and were willing to take action. It was a political movement as much as a legal one.

The way we crafted the case was a political argument because—I say this all the time—arguing in the Supreme Court is a lot like Sesame Street. You’ve got to learn to count and the only number that’s important is five. If those who oppose abortion have five votes, you can use the most persuasive arguments you can and you still can’t win. It’s not like we haven’t been making persuasive arguments to the high court on this issue for 40, 30 years—since 1973—that’s 45 years! The case has been reaffirmed 18 to 20 times by Supreme Courts.

Both stare decisis and persuasion are with us, but that is irrelevant if there are five conservative votes willing to take away or undermine women’s constitutional rights.

In my view, with Trump’s next appointment, it’s even clearer that there will be those five votes. So frankly, that same political strategy is necessary today: making sure Americans understand that in many states if Roe is overturned, state legislatures will work very quickly to eliminate rights of legal abortion for most women in the country. Those are the decision-makers that are going to be taking away women’s rights.

MJ: What will happen at the state level if Roe is overturned?

KK: First of all, there are four states that have already enacted statutes called trigger laws. Those will mean that under state law, should Roe be overturned, it would immediately criminalize abortion back to where it was prior to Roe. There are many other states in which there is Republican control of both houses and a Republican governor, where those who oppose abortion will introduce laws criminalizing abortion or enacting much more harsh restrictions than we’ve ever seen within a matter of days, if they haven’t already done so.

If you live in California and Oregon and Washington and New York state and Massachusetts, it’s pretty likely that abortion will remain legal like it was in New York and Washington before Roe. But if you live in the middle of the country, where there are fewer providers and many more Republican-controlled legislatures, those are the places where women will suffer the most. Those who are poor, those who are young, they are primarily the people who will suffer. In the days before Roe, women died from illegal abortions and from inability to have access to procedures. Their health will suffer again should we return to criminalized abortion.

Now, there are a lot of commentators out there saying, “Well this will never happen.” The reality is it already happened; the only thing that changed was Justice Kennedy changed his vote after initially voting to overturn Roe. We know that the court has that power.

MJ: What do you think made Kennedy change his mind and how likely is a turn like that today?

KK: I’d like to believe it was my great persuasion that changed Justice Kennedy. I don’t think so. I think what changed Justice Kennedy was a concern for the institutional integrity of the court, and the public outcry over losing a fundamental right for the first time in history. I think it concerned him that the court would be perceived as a political body based on the president that appointed the justice rather than the rule of law. I have no such confidence about the next appointment by a president who has less respect for the rule of law, and who is much more indebted to the right-wing ideologues of their party. I have much less confidence that the next justice will act as Justice Kennedy did.

MJ: Justice Thomas signed the dissent in Casey, so it’s clear that he is open to overturning Roe. What about other justices?

KK: There’s no doubt there’s four votes to overturn Roe on the current court. Alito ruled in Casey when he sat on the Third Circuit and he’s overwhelmingly anti abortion. He basically would have upheld the entire statute in Casey, and dissented when at least one provision which required women to notify their husbands [before having an abortion] was struck down.

Some people think, “Oh, well Justice Roberts might be our savior” because of his position in the Affordable Care Act case. I don’t think so. Justice Roberts was a protégé of Justice Rehnquist, who wrote the Casey opinion overturning Roe that was never published. Given everything that I know about him, I would not say that he would be a Kennedy on this.

MJ: After you won Casey, what did you think the future landscape of abortion rights in the US would look like? Did you think that at least legalized abortion is settled law?

KK: No, I never believed that this race was over, this issue was done. In this area of the law, I don’t think anything’s ever settled. I think the only way that it’s settled is if you have the power to make sure that new restrictions aren’t enacted. I’ve spent many years arguing in state legislatures against restrictions, so I’ve seen what happens when we don’t have the political power to kill these bills. In the five or six years following Casey, those who opposed abortion turned their attention to opposing gay marriage. But it didn’t go away—and gay marriage won’t go away either, because these groups use the issues as a way to grow political power.

Do we ever think sexism will go away just because there’s a law? Will sexual harassment go away just because of Me Too? No, because part of what we’re talking about: the right to choose abortion, the right to gay marriage, the right for women to be part of the workplace in a fair manner, it’s about equality. The fight over equality, that’s an issue that’s been with us since well before the founding of our nation and we can’t expect that sexism and homophobia will go away instantaneously. The culture has to change as well as the law.

We’ve seen progress in recent years, but progress is not the end. It’s a start.

MJ: What was your reaction to the news of Kennedy retiring?

KK: I was devastated. While Kennedy is a conservative justice, he was the pivotal vote on the two issues that I care very, very deeply about—a woman’s right to choose abortion and gay marriage—and the only hope for making arguments involving free speech, voting rights, and immigration. He voted very conservatively in the past term, but the next one’s going to be much worse than Kennedy.

MJ: The day that announcement came down, Jeffrey Toobin said on CNN that within 18 months abortion is going to be illegal in 20 states.

KK: I absolutely agree with him. It could be more, it could be a few less. The number is not exact but once the court gives the green light, many states will move to enact bans on abortion. If they can do it, they will. I think that the people who are saying, “Oh, it will never happen”—I would call that unwarranted optimism.

MJ: If it does happen this quickly, within 18 months, presumably the case before the Supreme Court will likely be one of the pieces of litigation that’s already moving through the courts right now.

KK: That’s correct.

MJ: Do you have predictions as to which case, or type of case, it could be?

KK: This is a fight about legalese, about what lawyers call the standard of review. Is it an “undue burden” test—the standard in Casey—which requires a state to justify new abortion restrictions? Or is it the lower “rational basis” test, which allows the state to do anything as long as it furthered the protection of fetal life in their view?

I don’t know the exact case it’s going to be, but just about any abortion case that gets to the court will give them the opportunity to revisit the legal standard for reviewing these kinds of cases. I don’t really think it matters what the restriction is, because once the court has the ability to review the standard they can say “Roe and Casey are no longer the law, we allow states to enact anything they want as long as it’s ‘rational.'” That’s what happened in Justice Rehnquist’s opinion that was never filed in Casey.

MJ: Where do the anti-abortion and pro-choice movements stand? What have been their greatest successes?

KK: The success of the anti-abortion movement has been that they’ve played the long game. They’ve been at this since 1973 and now the prize is at hand. That’s a very long game and they thought they were there in ’92. They weren’t, they kept at it. They understood the politics of winning majorities at the legislative level and in Congress and winning the presidency.

For pro-choice Americans, our greatest success has been that women are more equal today than they were in 1973 in a whole host of ways. We are a part of America and we are contributing as equal members on a daily basis in every field. As a result, our culture is demanding women’s equality and that will be our biggest success; because once the culture demands equality, the law will follow.

Let me give you an example: When I started working in this area in 1977, there were states in this country that didn’t permit no-fault divorce. Women could not get equal credit. Newspapers routinely had ads that said, “No single mothers or pets,” when renting apartments. There were all kinds of egregious things that were just routinely part of American life that demonstrated inequality for women. We’ve come a very, very long way in those 40 years. But every progress is fragile unless we—not just people my age but also the age of my daughters and younger women as well—are there 100 percent to protect it. And that’s really what this is all about.