Mother Jones; Lauren Victoria Burke/AP

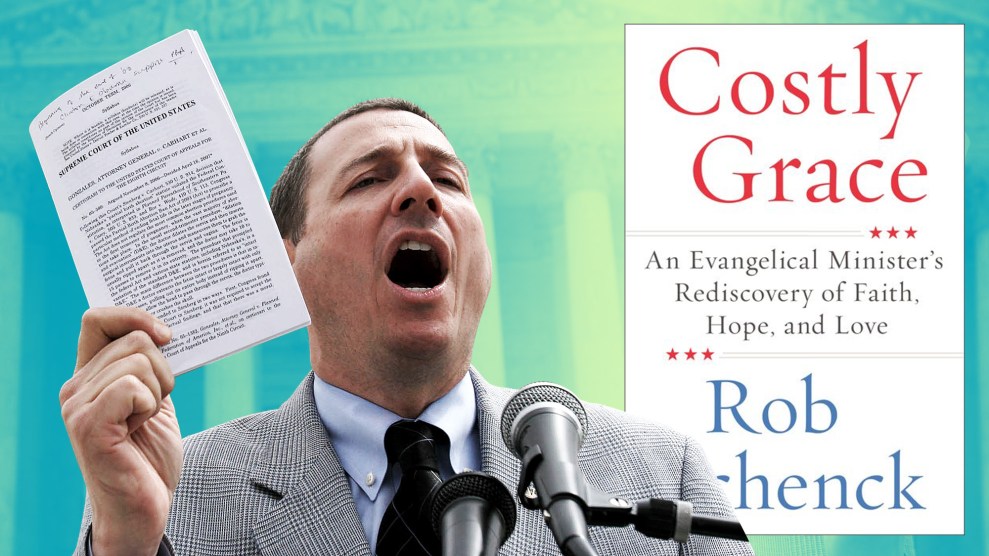

The past four decades have seen an ever-tightening alliance between American evangelicals and the Republican Party, and few have played as pivotal a role in fostering that coupling as Reverend Rob Schenck. The evangelical minister from Buffalo, New York, gained national notoriety in the 1990s as a fervent anti-abortion activist who orchestrated shocking stunts to promote his cause, including one in which an aborted fetus was thrust in the face of then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton. His keen ability to advance religiously conservative causes brought him to the nation’s capital and the epicenter of politically conservative power circles. During the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, he boosted the right’s anti-abortion and anti-LBGT agenda, netting great success with the Clinton-era Defense of Marriage Act and Bush’s partial-birth abortion ban.

But today, Schenck is, in many respects, unrecognizable. He’s distanced himself from many of his fellow evangelical pastors and former political allies, leaving his anti-abortion work behind in favor of another pro-life cause, though one uncommon among American evangelicals: gun control.

Schenck attributes this transformation to his late-career doctorate in ministry—specifically, his research on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor who questioned the symbiotic, and problematic, relationship that emerged between Adolf Hitler and 1930s German evangelical churches. Schenck began seeing parallels in the closeness between the American evangelical church and the Republican Party, and wondering if the religious institution to which he’d dedicated his life had become complicit in providing a spiritual veneer for a hate-filled political agenda. Schenck says the result of this codependence culminated in 2016, with four-fifths of white American evangelicals supporting President Donald Trump, whose behavior often stands in sharp contrast to traditional Christian values. Schenck, still an activist to his core, is now a voice of ethical reform in American evangelicalism and public policy, specifically on gun safety.

Schenck explores this Trumpian phenomenon and his personal evolution in his new memoir, Costly Grace: An Evangelical Minister’s Rediscovery of Faith, Hope and Love. He is self-critical as he explores the forces that gave way to the ultimate abandonment of his former values, highlighting particular moments when his thirst for power and influence overrode his pillars of faith. Ultimately, the work is a meditation on the thorny relationship between religious leaders and politicians, and the dangers that lie in getting too close to the sun.

I recently sat down with Schenck to discuss how evangelicals might extricate themselves from the moral contradictions of their Faustian bargain with the GOP, the “unwitting dupes” among his peers, and if disaffected evangelicals can be brought back into their faith.

Mother Jones: Let’s begin at the heart of the matter: Do you think faith and politics are inherently at odds with each another?

Rob Schenck: I do think there is an inherent tension between the two. And maybe that goes to evangelicalism’s prophetic role—in other words, the old hackneyed phrase “declaring truth to power,” holding government to account for its ethical and moral behavior. When the relationship is too relaxed between religion and government, when the two get along too well, that usually signals danger—the corruption of one or the other or both. And that’s when religion stops being the salutary player in the relationship and becomes an enabler, or loses its conscience and becomes toxic, which I suggest is what has happened to American evangelicalism.

The book is partly confessional. I’m disclosing my own weaknesses when it comes to all this. The temptation [to gain political influence] is enormous, especially when you start playing a public role, and certain rewards are set up for telegraphing certain messages and supporting political personalities and platforms. It’s very easy to be seduced by that, and to give into it. And then you become spoiled by it—it’s very hard to withdraw, and [when you do] you lose a certain measure of credibility, sometimes entirely.

MJ: When one examines the core tenets of Christianity, they seem incongruous with many of its followers’ beliefs—for example, on guns. How is it that evangelicals have come to be so receptive to messages that seemingly have so little to do with faith?

RS: It’s probably a number of things that work together. There’s certainly an assimilation that takes place in any religion; instead of the religion informing the culture, the culture informs the religion, and one gets the better of the other. It’s one of the ways I explain the phenomenon of popular gun culture within American evangelicalism. If you go to the West and you go to the South, there were the pioneers who were facing real dangers at the time. So there’s a survival instinct there that informs gun attitudes, and it’s very old—200, 300 years old—in some places in the United States.

You could look at those elements as somewhat benign, but then on the other hand, racism plays a role in a large sector of American evangelicalism. The churches of the South wanted to preserve the institution of slavery, and the churches of the North did not. You kind of had a reactionary evangelicalism. They said, “Oh no, you’re not going to tell us we’re bad people on this. This is our way of life. This is our social security and survival.” You almost have an assertion of that ugliness for the purpose of instructing the Northern churches, that they were the ones who were wrong. You have similar dynamics on various issues playing out today.

MJ: In the section of your book that describes your doctoral research on the parallels between 1930s Nazi Germany and present-day America, you write, “American evangelicals were on the brink of a moral disaster, as our pastors and other leaders lacked the theological tools to protect them from being cynically exploited by politically motivated actors.” What sorts of “tools” would you say could have protected them from being exploited by political actors?

RS: One is simply exercising self-doubt. We don’t do that very well in evangelicalism. In fact, evangelicalism is built on a platform of asserting one’s rightness—”I’m always right because the Bible is right.” We’re the ones who really believe the Bible; others have doubt. This is an error that is made within American evangelicalism, that doubt is the antithesis of faith, so when you express doubt, you’re somehow undermining the power of faith. And I don’t think we have tools for discriminating between the right kind of doubt and the wrong kind of doubt, or deleterious doubt and beneficial doubt. It’s not that [the Bible] affirms everything I want and believe—it doesn’t necessarily affirm me, it challenges me to do better, to be better, to think differently, to look at things differently, to do maybe what doesn’t come naturally to me.

MJ: Many of us who report on politics think, “How bad do things have to get before something gives?” I think you’ve explained in this book that rock bottom is not an inflection point for a lot of people—at that point, many people instead cling to the same behaviors that have long served them, even if it’s the ones that led them down this path. Do you think evangelicals see what’s happened with Trump as a low point, or do you think they’ll continue to support him and further his message?

RS: I certainly know people who are expressing that [this is a low point]. The problem is, when you have the kind of juggernaut now that’s in motion, the consequences of challenging it or breaking from it are enormous. They aren’t just inconvenient—they can be destructive. So you get to a certain momentum where stopping is as dangerous as anything else, and people tend to say, “I think I better ride this thing to the end, because if I stop now, it will destroy me.”

MJ: In Costly Grace, you mention the book your brother wrote in 1993 about the marginalization that evangelicals felt in popular culture or, as you write, the “unwitting conspiracy between modern education, the media, left-wing politics, and popular culture…bent on wiping out all vestiges of traditional Christian beliefs, practices, and adherents from the American landscape.” That argument seems to anticipate Trump’s ascendence by 25 years. While you spend a fair bit of time lamenting how evangelicals have lost their way, would you also argue that conservatives have co-opted the evangelical perspective for their own political gain?

RS: Yes, very much so—at first I think instinctively, and not necessarily consciously. But with time, conservative politicians understood the magic [of that appeal]. It became more and more intentional, if not scientific—the testing, the messaging, looking for sectors that respond in a certain way, and then that culminates in a master of it, mainly Trump, who gets it completely.

And I do think there are very close parallels with Germany 1931, 1932, and Hitler doing the same thing, and Christians in Germany were exhausted. Most of the population felt marginalized, especially among the working class, and inferior. They needed relief, and here was a personality and a political system that would give them instant relief from all that exhaustion. In some ways, never do I want to excuse the behavior that hurts so many people, but at the same time, the players in that are not always nefarious. Some of them are just—this is a shortcut to what they think is a good outcome. But it’s not. I hope I’ve planted some of the seeds of doubt about all that in the book.

MJ: When I was reading this, I was trying to figure out who this book is for. I could see this being helpful to someone who is evangelical, but as someone who is not, I got a lot out of it. Who did you have in mind?

RS: I really had three groups of people in mind: One was my evangelicals, my tribe—the people I still very much love. In some ways, I see them as unwitting dupes. They got played. Some of them I see as terribly vulnerable; we all give in to our worst impulses at moments, and I want to give them the benefit of the doubt. So I wanted to take them through the process I went through and let them observe it. If they identified with any part of it, and it’s helpful to them, that will be wonderful.

The other group I had in mind were the disaffected evangelicals, mostly young people who have left the evangelical fold. Part of the reason they can’t process [what has happened in the evangelical church] is because we have refused to name these failures. Once you name them, that can be very, very helpful to someone’s recovery.

And then I had a reader in mind who was just curious, trying to make sense of these evangelicals—what we really believe and how we think. I know it’s frustrating and infuriating for a lot of people, and they just think, ‘”What is in these people’s heads? What are they thinking?” You know, I think sometimes people imagine something much more sinister than is really present there. There are plenty of sinister impulses, but there’s a whole system at play.

MJ: So, when you look at the future, what do you think the result of the evangelical embrace of Trump will be?

RS: I say in the book that the Trump phenomenon may portend the total collapse of American evangelicalism, which for me would be sad, but not the saddest thing. We have an old phrase in evangelical parlance built on some biblical texts: “What the devil means for destruction, God means for good.” So, could God use this terrible thing in the end to bring about a better form of evangelicalism in America? We may reach a toxicity level where the patient must succumb, but we believe in resurrection, so out of death can come life…So, maybe this is the demise of what we now know as American evangelicalism, and largely, the Trump phenomenon is a symptom, rather than a cause. We made this terrible deal with Donald Trump because we were already demoralized. He didn’t demoralize us—he is the evidence of our demoralization.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.