After a family member was detained, Amal Hana joined hundreds of others in Detroit last June to protest the detention of more than 100 Iraqis.Tanya Moutzalias/AP

Iraqi nationals facing deportation from the United States say immigration officers tried to pressure them into signing documents stating that they want to return to Iraq voluntarily, despite fears that they will be tortured or killed there. The new allegations are detailed in an emergency motion filed this week by the American Civil Liberties Union that asks a federal judge to stop the alleged harassment and coercion.

The court motion, filed Wednesday, comes just over a year after Immigration and Customs Enforcement detained more than 100 Iraqi nationals. Some of those facing deportation do not speak Arabic or have never been to Iraq because they were born after their parents left the country, sometimes in refugee camps. Many are members of the Chaldean Catholic community that supported Donald Trump’s calls to eradicate ISIS during the 2016 campaign. The Chaldeans believe they will be persecuted and killed if they are sent back to Iraq.

For decades, Iraq refused to accept Iraqi nationals whom the United States wanted to deport. The lack of cooperation meant that the 1,444 Iraqis slated for removal could live with little fear of deportation. That changed last year, when Iraq agreed to accept deportees in exchange for getting off of the Trump administration’s travel ban list. Last June, ICE arrested more than 100 Iraqis with old removal orders.

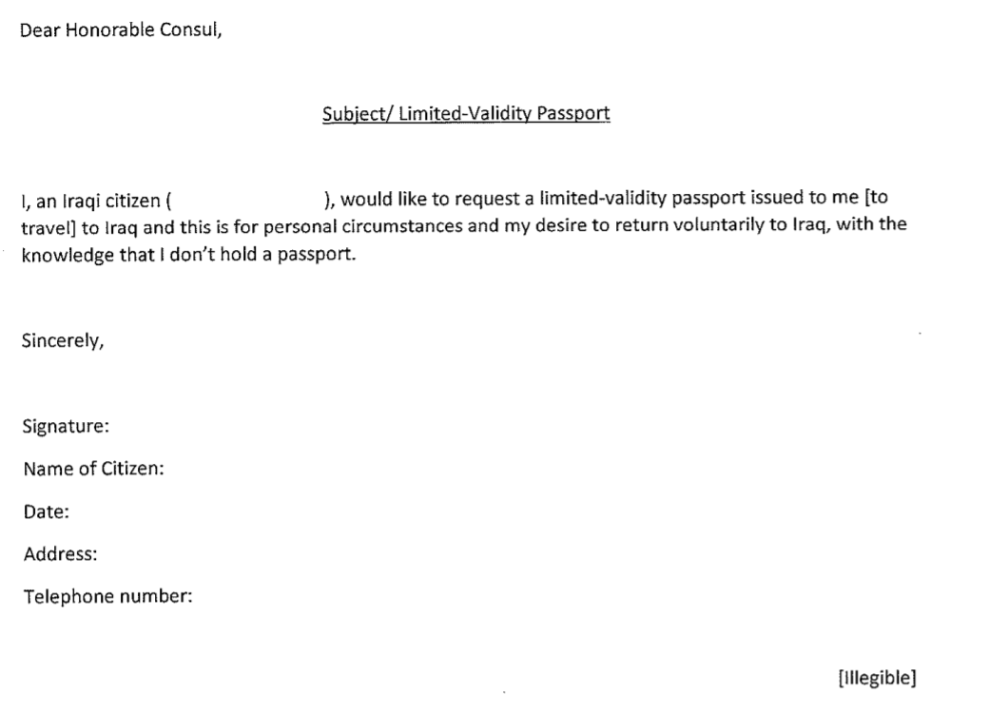

But for Iraqis to be deported, Iraq still needs to issue certain travel documents. And the ACLU motion states that Iraq doesn’t appear to be issuing those documents for everyone ICE wants to deport, but rather just for Iraqi citizens who say they are willing to leave the United States. ICE employees have threatened detainees with criminal prosecution if they don’t sign a form that says they have a “desire to return voluntarily to Iraq,” according to declarations included in the ACLU’s motion. Miriam Aukerman, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU of Michigan, tells Mother Jones that her organization began hearing reports that ICE was pushing people to sign the form about two weeks ago.

Two detainees say an Iraqi official told them they would spend their lives in prison if he didn’t sign it. Others were reportedly told by ICE that they would be sentenced to five years in prison for not cooperating. The ACLU states that ICE has no authority to prosecute them for not signing, but most signed anyway. A smaller group that refused was allegedly berated by ICE employees.

An English version of the form some Iraqis signed.

Justice Department lawyers stated in a response filed Friday that there has not been enough time to investigate the allegations but expressed skepticism about the detainees’ claims. The ICE officer in charge of obtaining the travel documents said in a declaration that he did not threaten any detainees with criminal prosecution. The government’s lawyers also said that Iraq has not refused to provide travel documents to people who don’t sign the form. Instead, they say “further approval” is needed from Baghdad to issue the documents. (The government’s response also states that two detainees were denied citizenship by Iraq, one of whom Iraq believes is Palestinian.)

A 2001 Supreme Court decision prevents the government from holding people in immigration detention indefinitely if they cannot be deported. That means that the Iraqis who don’t sign the documents would eventually have to be released if Iraq decides against taking them back. Along with the threats of prosecution, two detainees say they were woken up and told they were being flown back to Iraq. Both feared they would be tortured there. “I was in fear for my life,” one of them said in a declaration to the court included in the ACLU filing. “I could not contact my attorney to tell her what was happening.” It was only when he got to the airport, he said, that he learned he was not being sent to Iraq.

Mother Jones reported last year on the danger that Iraqis could face if they are deported:

Michael Steinberg, the ACLU of Michigan’s legal director,…argues that deporting the detained Iraqis is illegal. Under US law, individuals can’t be sent to countries where they are likely to face torture or persecution. Steinberg and many Chaldeans argue that sending Catholics, Kurds, and Iraqis who identify as American back to Iraq would be an effective death sentence. Kinaia [a Chaldean storeower] says the arrested Iraqis, some of whom he knows, are better off being executed than deported, because “at least they could be buried here.”

Steinberg has never worked a death penalty case because capital punishment is illegal in Michigan. “But this is as close as I’ve come,” he says. “There’s great fear and panic within the community that their loved ones are going to be sent back to Iraq to be killed.”

After the arrests last June, ICE pushed to keep the Iraqis in detention and quickly deport them. Mark Goldsmith, a federal judge, blocked the deportations so “those who might be subjected to grave harm and possible death are not cast out of this country before having their day in court.” In January, Goldsmith ruled that the detainees have a right to bond hearings, and many have now been released from immigration detention.

But dozens, particularly those with previous criminal convictions, are still detained. Immigration detention is not supposed to be used to coerce people into accepting deportation, but Aukerman, the ACLU lawyer, says that is exactly what is happening. Some of the Iraqis have already given up on their cases and agreed to return to Iraq in order to get out of detention, she says.

“It is heartbreaking to go into these facilities to talk to these detainees who are just desperate to get out of detention,” Aukerman says. “And ICE, frankly, banks on that.”