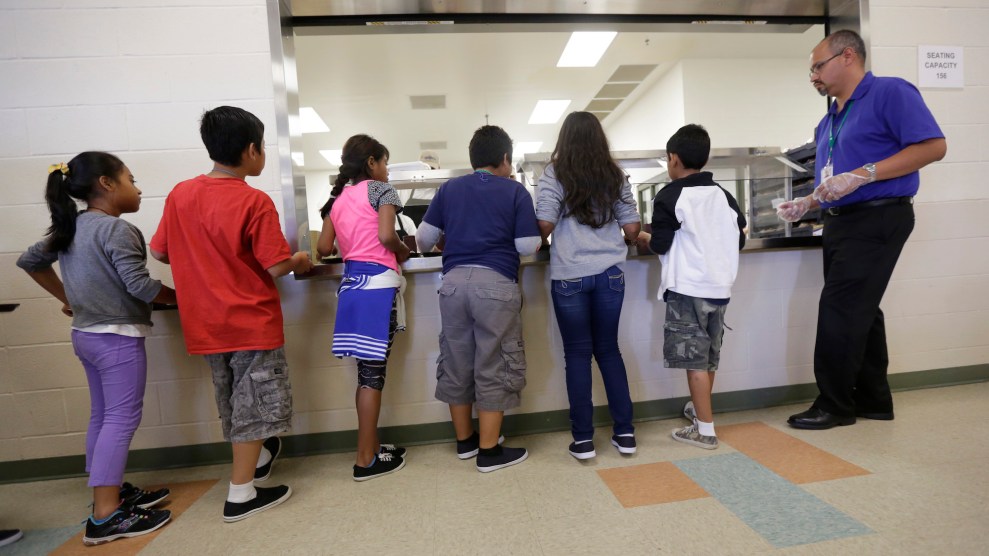

Detained immigrant children line up in the cafeteria at the Karnes County Residential Center in 2014.Eric Gay/AP

There’s still widespread uncertainty about how exactly the executive order signed by President Donald Trump on Wednesday will change his policy of separating and detaining immigrant families. But one thing is clear: If the White House can’t deter or deport families arriving at the US-Mexico border, it wants to put them behind bars.

According to Trump’s June 20 executive order, the Department of Homeland Security will detain families while adults are prosecuted for illegal entry or as they wait for asylum claims to be processed. Due to a federal ruling known as the Flores settlement, which prohibits the government from locking up migrant children for more than 20 days, it’s probably impossible for Trump to keep families in detention indefinitely right now. So the executive order also pushes Congress and the attorney general to try to find a way around Flores—which Jeff Sessions is already trying to do.

If they succeed, immigrant rights advocates warn, families could be kept together but held as long as their cases are pending—a policy that could continue to harm kids psychologically. “Changing one form of trauma for another is not a solution,” says Michelle Brané, director of the migrant rights and justice program at the Women’s Refugee Commission.

Family detention centers, sometimes known as “baby jails,” aren’t new. The Obama and Bush administrations held migrant families in detention centers for months on end, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement still keeps around 2,500 parents and children in three facilities. Those include two large facilities run by private prison companies in tiny south Texas towns, plus a publicly operated detention center in a former nursing home in Pennsylvania. Family detention centers must meet higher standards than adult-only detention centers and cost taxpayers more than $300 per detainee per day.

Together, ICE’s family detention centers have the capacity to hold approximately 3,650 people. As of June 4, those family detention centers were about 70 percent full, according to ICE. With Border Patrol agents apprehending roughly 9,000 “family units” per month along the US-Mexico border since March, Trump’s “zero tolerance” border policy could fill up the existing family detention centers quickly.

That’s why Trump’s executive order paves the way for DHS to hold families in other federal facilities and on military bases. It even authorizes the Defense Department to construct new detention centers for immigrant families if necessary. On Thursday, a Customs and Border Patrol official told the Washington Post that the agency is seeking to “accelerate resource capability” to allow ICE to “maintain custody” of families, while the Defense Department said it would hold up to 20,000 unaccompanied migrant children on military bases in the coming months. And Congress is playing along: The so-called “compromise bill” being considered by House Republicans would free up $7 billion for family detention.

“This is not going to be some family residential center,” says Kerri Talbot, legislative director for The Immigration Hub, a pro-immigration strategy group. “It’s going to be prisons. It’s going to be military bases and other prison-like facilities.”

There’s some precedent for using military facilities to detain immigrant children and families on the border. In the summer of 2014, during a surge of unaccompanied minors from Central America, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement sent thousands of children to temporary shelters at military bases in California, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Around the same time, the Obama administration opened a temporary detention center for migrant families at a federal law enforcement training center in Artesia, New Mexico—part of what then-Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson called an “aggressive deterrence strategy.” The Artesia camp promptly faced a torrent of complaints: a lack of child care, inappropriate food for children, limited access to telephones, and violations of due-process rights.

“I remember how I felt sick to my stomach when we walked through the cafeteria and I saw nothing but a line of high chairs as far as I could see,” recalls Karen Tumlin, director of legal strategy at the National Immigration Law Center, who was one of the first attorneys to visit the camp. She remembers being surrounded by mothers desperate for help with their asylum cases but unable to see their lawyers in the rural New Mexico town where they were held. “They thought they had finally left behind a life of constant fear,” Tumlin says. “And when they got to the United States they were living a new nightmare.”

Artesia closed after five months, but it was succeeded by the 2,400-bed South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, run by CoreCivic, the country’s second-largest private prison company. It wasn’t CoreCivic’s first time locking up immigrant families. During the Bush administration’s post-9/11 crackdown on immigrants, the company—then known as the Corrections Corporation of America—opened the T. Don Hutto Residential Center on the site of a former medium-security state prison in Texas. There, according to the ACLU, kids were put in prison uniforms, families were kept in cells 12 hours a day, and children couldn’t keep pencils, stuffed animals, or crayons in their cells.

ICE stopped sending families to Hutto in 2009. CoreCivic’s detention center in Dilley still holds families—about 2,000 people as of June 4, according to an ICE spokesperson. DHS currently pays CoreCivic roughly $200 million per year for the facility. It also pays the GEO Group—the country’s largest private prison company, which holds about 32 percent of all immigration detainees—to hold families at the 1,158-bed Karnes County Residential Center in Texas.

Perhaps the only winners amid the crisis sparked by Trump’s family separation policy are CoreCivic and GEO, which saw a 3.5 and 1.8 percent bump in their respective stock prices after the president signed his executive order on Wednesday.