Mother Jones; Cheriss May/NurPhoto/ZUMA; CDC

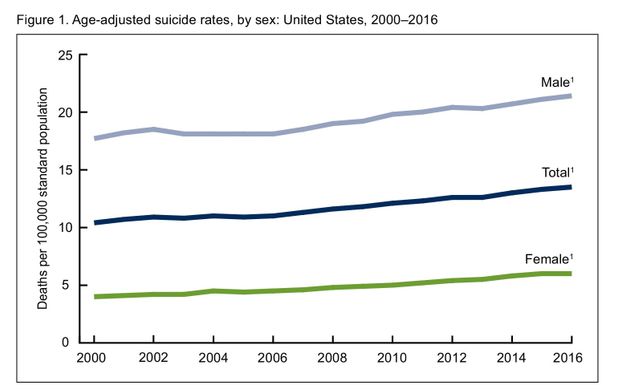

A week after the back-to-back suicides of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain renewed the national conversation over mental health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released numbers showing that America’s overall suicide rate has climbed by a whopping 30 percent since 2000.

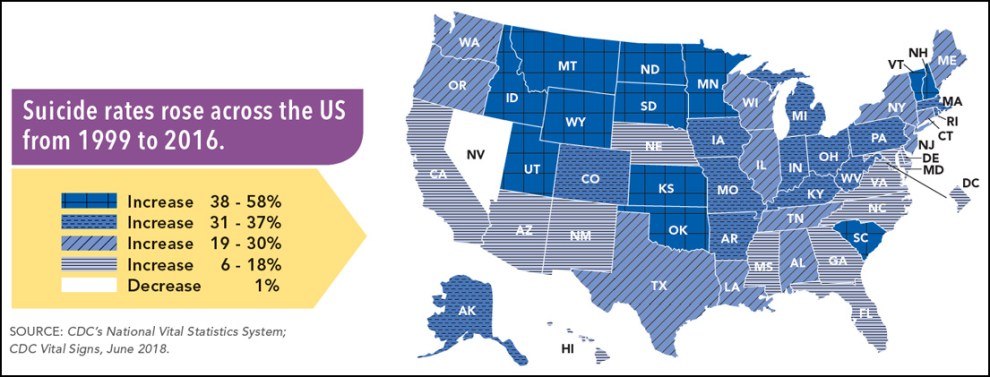

On Thursday, the CDC released a second report that breaks down the data on the nearly 45,000 Americans who took their own lives in 2016, making suicide the 10th leading cause of death. Every state except Nevada saw an uptick from 1999 to 2016, and within certain demographics, those upticks were disturbingly dramatic. Among the key findings from the new report and the CDC’s mortality database:

- America’s overall suicide rate has climbed by an average of 2 percent per year since 2006, double the annual increase from 2000 to 2006.

- North Dakota saw the biggest increase from 1999 to 2016: 58 percent.

- Montana had the highest suicide rate in 2016: 25.9 deaths per 100,000 residents.

- New Jersey had the lowest rate: 7.2 per 100,000.

- California, a populous state, had the most suicides: 4,294

- Of the 44,965 Americans who died by suicide in 2016…

- 77 percent were male.

- 51 percent used a gun.

- A firearm was by far the most common method for males 15 and older. More than 80 percent of suicides by elderly men (75 and up) involved a gun.

- Although their numbers were relatively small (171 nationwide), suicides by girls ages 10 to 14 nearly tripled from 2000 to 2016.

In a blog post last week, Mother Jones‘ Kevin Drum noted that the United States isn’t the only nation with an increase in suicides. But here at home, where President Donald Trump claimed he would “tackle the difficult issue of mental health” in the wake of the Parkland shootings, his administration has done little on the issue.

In fact, the administration’s 2019 budget proposal, released in February, revealed priorities that swing the opposite way. Trump proposed brutal cuts to Medicaid, the largest insurer of treatment for mental health problems and substance abuse, as well as to Medicare and Social Security Disability Insurance. All told, the cuts could add up to almost $1 trillion—and would disproportionately affect the nation’s most vulnerable citizens.

And then there’s the gun problem. In 2016, nearly 23,000 Americans took their lives with a firearm. It was the most-used method by far among men and adolescent boys, which may help to explain the large gender disparity in suicide deaths, as women are more likely to attempt suicide by less-lethal means. Despite the president’s lip service after the mass shootings on his watch, the Trump administration has rolled back regulations that made it harder for people with mental illnesses to purchase a gun. Shortly after he took office, Trump signed a bill revoking Obama-era legislation that would have added people receiving Social Security checks for mental illnesses, and people deemed unfit to handle their own financial affairs, to the national background check database.

Mental health advocates also are concerned about Trump’s latest attack on the Affordable Care Act: a proposal to expand short-term limited insurance plans. Unlike other types of health insurance, these plans need not cover preexisting conditions including mental illness or cover mental health and substance abuse care. The National Alliance on Mental Health, for instance, fears that the proposed changes will raise premiums on people seeking access to treatment, or leave people without mental health coverage.

A 2017 report from Mental Health America, a national nonprofit, found that more than 43 million citizens suffer from a mental health condition yet fewer than half had received treatment in the previous year. The report also highlighted a major shortage of providers. In Alabama, for instance, there is only one mental health professional for every 1,260 residents.

Dr. Holly Hedegaard, the lead author of the latest CDC report, told me that while the data cannot predict future trends, it highlights how suicide rates are climbing faster now than they were before 2007. “We need to be aware,” she said. “And we need to try to prevent these things from happeninga.”

Mark Olfson, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, said limiting access to guns and other lethal means could help, as could extending awareness of suicide resources such as hotlines and improving detection of suicidal behavior in schools and health care settings. He also noted that greater attention needs to be given to people arriving in emergency departments following suicidal behavior, and to patients discharged from psychiatric hospitals.

“Halting and eventually reversing this grim trend will require a sustained and concerted focus on societal, community, and clinical targets,” Olfson said. “It is a public health problem without a simple solution.”

If you or someone you care about may be at risk of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, a free, 24/7 service that offers support, information, and local resources: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

This article has been updated.