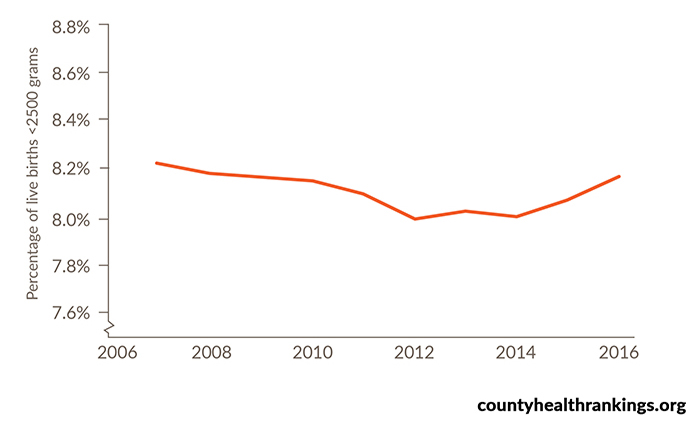

For decades, the number of American babies born too small was on the decline. But new data suggests the rate may be ticking up again—especially among African Americans.

The World Health Organization defines an underweight newborn as weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces. In 2016, according to new joint report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute’s annual county health rankings, 8.2 percent of new babies failed to exceed the threshold. That’s a 2 percent increase in underweight births since 2014. (The United States also fares poorly compared with other nations. See this Brookings Institution chart, based on 2011 data.)

Babies can be born too small for a number of reasons: Most commonly, it’s because they are premature or because the mother’s placenta isn’t providing enough nutrients. Low birth weight is associated with a range of health problems, from infections and brain bleeds in infancy to a higher risk of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease later in life. Birth weights are a good general indicator of the health of a community, says Julie A. Willems Van Dijk, a University of Wisconsin public health scientist and a lead researcher on the report. “It’s very useful because it not only talks about infants but it’s also a reflection of maternal health.”

The researchers found that low birth weights were especially pronounced in the Southeast and parts of the Southwest. In some states, the rates varied widely by county—take Colorado, where rates ranged from 7 percent in some counties to more than 12 percent in others.

But even more striking were the racial disparities. The low birth weight rate for black babies was 13 percent, compared with 7 percent for white and Hispanic babies and 8 percent for Asian and Native American babies. (The study did not break Asian Americans into ethnic subcategories.)

To show just how dire the disparity is for African Americans, the researchers compared the underweight birth rate for black babies in each state with the overall rates for that state’s lowest performing counties. In every case, the statewide rate for black babies was worse than the rates for those counties.

That trend parallels recent reporting that giving birth is more dangerous for African American women than for their white counterparts. Compared to Caucasians, black women are up to four times more likely to die during childbirth—and their babies have a higher risk of dying, too.

Poverty, lack of prenatal care, and poor maternal nutrition all seem to be associated with low birth weights. The data also suggests that for black moms, the stress of living in a highly segregated neighborhood may contribute as well: In highly segregated counties, up to 14 percent of African American babies are born low birth weight, compared with just 7 percent of white babies in those same counties.

Closing the racial gap will be complicated, Willems Van Dijk told me. “It’s not just medical care; we need to look at issues like segregation and living in a neighborhood that doesn’t have access to healthy food and jobs,” she says. “These are fixable problems, but it is going to take the right kind of action.”