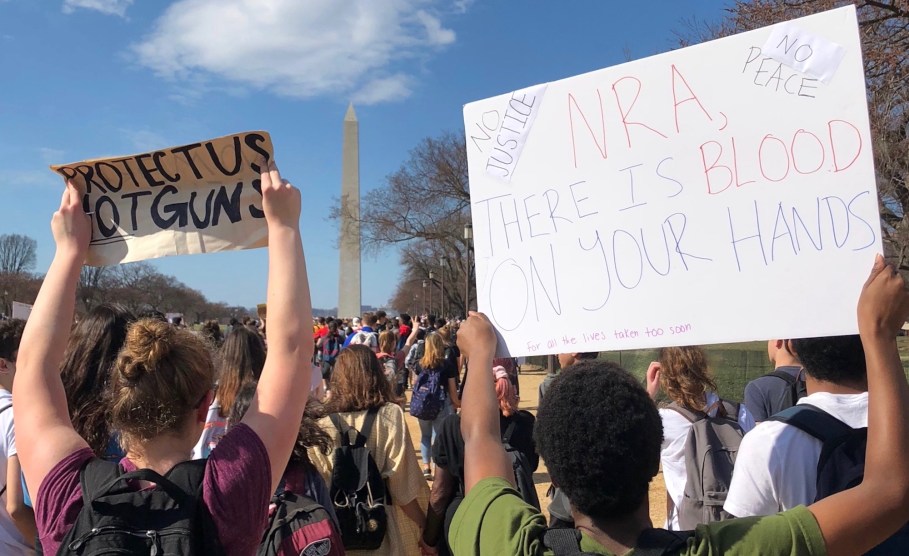

Students from schools around Washington, D.C., march from the Capitol to the White House demanding gun control reform on Wednesday, February 21.Kara Voght/Mother Jones

When high schoolers took to the nation’s streets and state capitals last Wednesday to demand gun control reform, the Internet was quick to celebrate their assertions of First Amendment rights. Oprah Winfrey weighed in, saying the moment reminded her of the 1960’s Freedom Riders who protested racial segregation in the South. And former president Barack Obama offered a tweet of praise and reminded his 100 million followers that “young people have helped lead all our great movements.” Under most circumstances, cutting class might warrant a trip to the principal’s office. But many high schools opted not to punish student demonstrators. Meanwhile, more than 200 colleges and universities have promised to turn a blind eye to any admitted #NeverAgain senior who might have faced disciplinary action for walking out of school.

In many ways, Obama’s history lesson checks out. After all, the Twenty-Sixth Amendment, which lowered the voting age to 18 in 1971, certainly arrived in response to demands from vocal student activists. But not every student protest in history has resulted in substantive change, nor have they always been supported by the high schools and colleges where they took place. In fact, the responses to student activism in the wake of the Parkland, Florida, shooting might be among the few times academic institutions have overwhelmingly celebrated student protests instead of restraining them.

During the golden age of student activism in the 1960s and 70s, student protesters were frequently punished for their demonstrations against the Vietnam War, or in support of the civil rights movement, says Mitchell Hall, a professor of history at Central Michigan University who studies social movements. Universities responded in a number of different ways, but in many cases, students who had participated in demonstrations were removed from school. For instance, Albany State expelled students who had been arrested for disturbing the peace when they protested alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Freedom Riders in early 1960s. Harvard kicked out 26 students in 1969 after they occupied a campus building and refused to leave while protesting the school’s ROTC program during the Vietnam War.

In fact, activism-inspired expulsions were common fare at that time—the first half of 1969 alone saw almost a thousand students suspended or expelled for campus protest activity. In some cases, the consequences of demonstrating could be life or death: male students who were expelled could lose their student deferments, Hall says, which made them draft bait. What’s more, students’ demands were often ignored: universities operated as in loco parentis—a Latin term meaning “in place of the parent”—during this period, where students were considered to be children who needed discipline and supervision, not adults whose First Amendment rights deserved protection.

This began to shift in 1969 with the Supreme Court decision Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, which upheld an Iowa high school student’s right to wear an armband to school in protest of the Vietnam War, thus sanctioning students’ right to free speech. “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” the opinion read, noting that students could not be disciplined unless their actions disrupted educational activities. And even then, according to Vera Eidelman, a legal fellow at the American Civil Liberties Union, the punishment could not be more severe because of the message expressed. Even when the school can punish students for their actions, it cannot punish them for their ideas. In other words, the consequences for cutting class should be routine, whether the occasion is Senior Skip Day or a march on the U.S. Capitol.

Fewer students have faced disciplinary action for their activism in the post-Tinker era, Hall says. During Black Lives Matter-inspired anti-racism protests of 2015, for example, disruptive protest behavior was typically addressed through conversations between student activists and campus leadership. The protests proved effective: student demands and actions led to college president resignations, reformed policies, and renamed campus buildings.

Punishment hasn’t ceased completely, and what kind largely depends on whether the school is a state institution, which is strictly subject to First Amendment protections, or private, which means the institution is free to exercise more control over what takes place on its property. This disparity was underscored with reactions to racially-charged incidents over the last year. Middlebury is a private college that has said it will view punishment for participating in gun control reform walkouts “in light of its belief that students are active members of our society and have political rights and obligations.” But last year more than 60 Middlebury students were put on probation for disrupting a talk by libertarian political scientist and writer Charles Murray and accusing him of espousing racist ideas. Last fall, administrators at William & Mary—a state university that has affirmed its commitment to admitted high schoolers who protest—condemned members of the school’s Black Lives Matter group for shutting down a talk by an ACLU representative. Administrators stated these students violated the school’s Student Code of Conduct—but the school would not comment on how the student protesters were disciplined.

The contrast between reactions to anti-racism initiatives and the recent demonstrations about guns illustrate just how much discretion schools have in dealing with student protests. One important factor influencing their decisions since the shooting, says Chris Finan, the executive director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, is the fact that the public is generally on the students’ side, so “the outrage being expressed is on a much broader scale, and with a great deal more sympathy, than what we saw with Black Lives Matter.” Last week, a CNN poll found that seven out of ten Americans want stricter gun laws. By comparison, only 43 percent of Americans have a positive view of Black Lives Matter, according to polling conducted last summer. “When you took the temperature of football fans at games where athletes were kneeling, you had pretty strong public opinion against the movement,” Finan continues. “But here, you have very large public support, so there’s a lot more sympathy on the part of public officials for these protests.”

Popular support has moved in lockstep with schools’ willingness to permit and encourage student activism on their campuses. Citing protests against the Vietnam War, Hall says that student activism efforts were initially met with resistance, “but American society evolved during those years such that dissenting positions became mainstream and gained support.” Students who rebelled against the Vietnam War early on, when less than a quarter of Americans disapproved of military action there, faced more disapproval of their activism efforts than near the war’s end, when sixty percent of Americans agreed with them. Recent student efforts to change gun laws would suggest the pattern holds: last week’s favorable polling in favor of gun control hit a high watermark of support unseen since 1993.

That willingness also comes from a renewed commitment by higher education to teach students how to skillfully engage in a democratic society, an educational mission that has come under increased fire by Republican lawmakers and GOP supporters during the Trump administration’s first year. Schools have affirmed this position in their messages to admitted students, often citing “civic engagement” as a core value and sufficient reason to ignore sanctions from high schools in response to student protests. Amherst College wrote in a Facebook post that “First Amendment rights are among the most prized of Amherst’s values and the college encourages all students to engage in civil and meaningful discourse on issues of critical importance.”

This latest surge in student activism also has expanded the sharing of information and new approaches by schools to provide forums for students to air their concerns. The ACLU, for example, is hosting a virtual training for student activists, while NCAC has urged school districts that may be resisting walkouts, to dedicate an assembly or class period to discussing the issues.

Will all this student activism result in substantive policy action from the legislative or executive branch? Hall is cautiously optimistic about the outcome of these efforts, even though lawmakers have yet to act. “I see some differences here, in that young people are actually being listened to,” he observes. “In many ways, that’s different than what we saw in the 60s and 70s.”