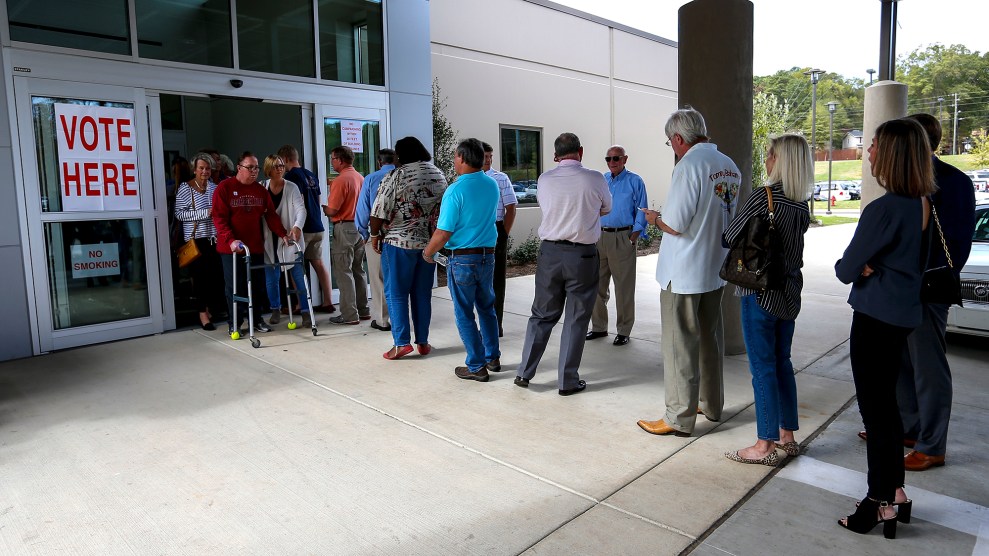

Voters wait in long lines to cast their vote in the 2016 election in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Butch Dill/AP

This time last year, Alabama’s chief elections official landed in the national spotlight for delivering a screed against nonvoters that many people interpreted as an attack on African Americans in the state, who have long faced barriers to voting. “If you’re too sorry or lazy to get up off of your rear and to go register to vote, or to register electronically, and then to go vote, then you don’t deserve that privilege,” Republican John Merrill said in an interview with documentary filmmaker Brian Jenkins. Jenkins had asked why he opposed automatically registering Alabamians when they reach voting age, and his response sizzled with anger toward people who “think they deserve the right because they’ve turned 18.” So he made a pledge: “As long as I’m secretary of state of Alabama, you’re going to have to show some initiative to become a registered voter in this state.”

In the year since he made those comments, Merrill has in many ways made good on his promise. When Alabamians go to the polls on Tuesday to elect Republican Roy Moore or Democrat Doug Jones as their new senator, an untold number will not participate due to the decisions made by Merrill’s office—which is in charge of ensuring a fair voting process—and by the Republicans who run the state. These laws and policies overwhelmingly make it harder for minorities to vote.

The election has captured national attention for pitting Moore, an anti-gay zealot accused of sexually assaulting teenagers, against Jones, a former federal prosecutor known for prosecuting KKK murderers. Alabama is a deeply conservative state, and it’s a testament to Moore’s unparalleled weakness as a candidate that the race is close. Most recent polls show Moore with a single-digit lead.

When the votes are tallied Tuesday night, what won’t be counted is how many people might have voted if not for the restrictive voting laws in place in the state. In a close election, the actions of Merrill and the GOP could help elect Moore.

In recent years, Alabama Republicans have taken steps to protect their grip on power by making it harder for African Americans and Latinos to vote. They passed a law requiring voters to show a government-issued photo ID, a measure that has been found to disproportionately disenfranchise African Americans and Latinos, who are more likely to lack such an ID and face impediments to getting one. The ID law also applied to absentee voting, which is used by many elderly black voters in rural counties, who now must mail in copies of their photo IDs with their ballots. (The NAACP Legal Defense Fund is challenging the law in federal court as intentionally discriminatory.) They reformed campaign finance laws to weaken the political organizations that mobilize African American voters. They closed 31 DMV offices across the state, disproportionately affecting rural majority-black counties. In every county in which African Americans made up more than 75 percent of registered voters, the local DMV was slated for closure. (After a federal civil rights investigation, Alabama agreed to increase DMV service in rural African American counties, partially reversing the closures.) Since the US Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, allowing states like Alabama to change voting procedures without federal approval, Alabama has closed about 200 voting precincts, creating longer lines and sowing confusion among voters.

“Alabama’s definitely in the forefront of voter suppression efforts,” says John Zippert, the head of the New South Coalition, a black political organization that seeks to mobilize African American voters. The spate of new laws has “definitely hurt us,” he says.

Merrill, who served in the state legislature for four years, was a co-sponsor of the voter ID law. After becoming secretary of state in 2015, he defended the DMV closure plan by promising that it wouldn’t disproportionately hurt African Americans, a claim the federal government later found untrue. Merrill has declined to advocate for early voting in Alabama, which often boosts minority participation. Absentee voting in the state is available to people who are out of town, ill, disabled, or work a shift of at least 10 hours that coincides with polling hours on Election Day. In January, Merrill said that if absentee voting were expanded to all registered voters, he would advocate for a voter ID requirement to receive an absentee ballot application.

Merrill has also made decisions as secretary of state that will likely result in fewer Alabamians being able to vote on Tuesday. Earlier this year, Alabama passed a law extending the right to vote to thousands of residents previously barred from voting for low-level felony convictions. But Merrill decided this spring that his office would not reach out to these individuals or more broadly promote the new law to the people who might now be able to register. “I’m not going to spend state resources” to notify “a small percentage of individuals who at some point in the past may have believed for whatever reason they were disenfranchised,” he told the Huffington Post in June. The reason they believe they cannot vote is that state or county election authorities informed them they were permanently disenfranchised, and no one has since told them otherwise.

The Campaign Legal Center, a voting rights nonprofit, filed a lawsuit this summer alleging that Merrill has “refused to take any meaningful action to implement HB 282 and advise voters of their rights, including publicizing the new eligibility requirements on the Secretary of State’s website, updating voter registration forms, or issuing guidance to registrars.” As part of the suit, the group sought, unsuccessfully, to get a judge to force Merrill to promote the new law. In August, Merrill’s office put out a press release about the law.

Asked whether Merrill’s office has done further outreach, his spokesman, John Bennett, says the office worked with the State Board of Pardons and Paroles to place posters in state prisons with instructions for incarcerated individuals to apply for voting rights reinstatement. Though the poster includes a list of felonies that result in disenfranchisement under the new law, nowhere does it mention the new law or the fact that some felonies no longer result in disenfranchisement.

Bennett denies that Merrill is trying to restrict the right to vote. “To see that there is worry that we are in any capacity making it harder for people to vote, it kind of goes against the core of what our goal has always been,” he says. He notes that Merrill implemented online voter registration and has a mobile unit that travels around the state providing free photo IDs for voting. He says Merrill has registered over 700,000 voters in Alabama, more than any previous secretary of state.

But voting rights advocates say Merrill has failed to inform ex-felons of their right to vote. “I think what we’re going to see is that a lot of people are being effectively disenfranchised by the state’s lack of public education around this law,” says Blair Bowie, a fellow at Campaign Legal Center. The group has done its own outreach to ex-felons in Alabama, including information sessions and street canvassing across the state, to try to get the word out about the new law. “I encountered tons and tons of people who were eligible to vote and think they are not,” she says.

Ex-felons who are uncertain about their eligibility could be scared away from registering for fear of prosecution. Bowie says it’s difficult to reassure felons that they can register if they were last told by state officials that they could not, particularly since the registration application threatens jail time for false information on the application.

In October, Merrill claimed that nearly 700 people had voted illegally in the September Republican Senate primary runoff election, which Moore won to become the party’s nominee. He alleged that people who had previously voted in the Democratic primary had crossed over to vote in the Republican runoff. The state banned such crossover voting earlier this year, though Merrill’s office did little to publicize the change. Merrill said he would hand over the names of alleged crossover voters to prosecutors and urged them to punish the guilty to the maximum allowable sentence. “In our republic, ignorance of the law has never been viewed as an excuse,” he said at the time. Rep. Terri Sewell, Alabama’s sole Democratic representative in Congress, said prosecuting Alabamians for breaking a new, little-known law was “a modern-day voter intimidation tactic, in line with a long and problematic history of voter suppression throughout the State.”

But Merrill’s claims turned out to be overwrought. When county probate judges began to review the names, they found scant evidence of any crossover voting. Of the 380 names Merrill submitted in Jefferson County, the state’s most populous county, the probate judge found zero instances of crossover voting. The Huffington Post contacted several other probate judges in Alabama who were unable to confirm any instances of crossover voting. Merrill, his critics claimed, had threatened prosecution and prison time for voters with no real evidence.

Last November, Jenkins, the documentary filmmaker, tweeted his assessment of the voting process in Alabama: “what I learned in AL: the registration process is complex and complicated.” Five minutes later, Merrill tweeted a response: “as a resident of CA you’re not registered to vote in AL & if UR we will be happy to prosecute.”