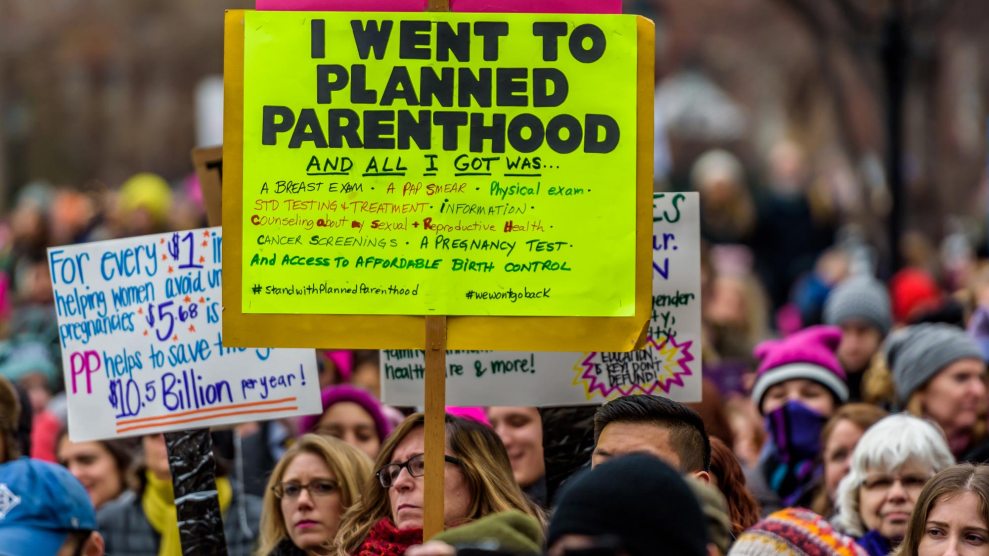

Olivier Douliery/CNP/Zuma

The Trump administration officially issued a new rule Friday that weakens the Affordable Care Act’s mandate requiring employers to provide free birth control as part of health insurance plans.

The final rule resembles a draft that was leaked back in May. It vastly expands the types of employers that can opt out of birth control coverage and eliminates some of the hoops those employers have had to jump through to do so.

“With this rule in place, any employer could decide that their employees no longer have health insurance coverage for birth control,” Cecile Richards, president of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, said in an emailed statement. “The Trump administration just took direct aim at birth control coverage for 62 million women.”

Under the Obamacare provision, some employers with religious affiliations could opt out of the birth control mandate, citing their religious beliefs. To do so, they had to file paperwork with the government indicating their objection, in turn triggering separate contraceptive coverage for employees provided directly by the insurance company.

“Under the Affordable Care Act, religious organizations already have an accommodation that still ensures their employees get coverage through other means,” Dana Singiser, vice president of public policy and government affairs for Planned Parenthood Federation of America said on a press call. “This rule is about taking away women’s fundamental health care, plain and simple.”

The Trump administration’s new rule expands this exemption, allowing virtually any organization, not just a religious one, to opt out of the mandate if they feel contraception coverage violates their religious beliefs or “moral convictions”—a much broader (and murkier) standard than before.

The new rule also strips out the provision requiring employers opting out of birth control coverage to notify the government they are doing so; now they’re only required to notify employees of a change in their insurance plans. Insurance companies could also themselves refuse to cover contraception if it violates their religious or moral beliefs.

Obamacare’s birth control mandate has faced a number of legal challenges since the ACA’s enactment in 2010. When the law was passed, there were no exceptions to the contraception mandate. That changed with the first Supreme Court challenge to the provision, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby in 2014, which led to the exceptions for religious employers. But some groups felt that even this accommodation was insufficient: In a followup 2016 Supreme Court case, Zubik v. Burwell, a number of religious organizations argued that the exemption still requires them to violate their beliefs because the necessary paperwork, in which they state their objection, triggers separate contraceptive coverage. The Supreme Court sent the case back to the lower courts in hopes that the religious groups and the government could work out a solution. No resolution has yet been found.

But by eliminating the requirement that objecting groups inform the government when they opt out of birth control coverage, it’s possible Trump’s new rule will provide a defacto end to this litigation. Women employed at companies that are opting out will now have to pay for contraception out of pocket. More than 55 million women currently have access to free birth control thanks to the Obamacare mandate.

It is likely that some employers will move quickly to take advantage of this expanded exemption. A study released in August by the left-leaning Center for American Progress found that for-profit, non-religious employers had already sought to exploit the religious accommodation built into Obamacare in order to avoid paying for birth control. The think tank found that more than half of the 45 applications submitted to the health department between January 2014 and March 2016 for an exemption came from for-profit companies, often in industries unrelated to religion, like tax services, landscaping, agriculture, or construction.

The new rule has been published as an “interim final rule” in the Federal Register, which means it goes into effect immediately, rather than going through the typical notice and comment period. Even though it is already in effect, there is still a comment period that will end December 5.

You can read the full rule here: