On a sunny Southern California morning, Courtney Everts Mykytyn smiles into her laptop camera and greets seven moms spread around the country, from Buffalo, New York, to Richmond, Virginia. “I’m Courtney. I have two middle school kids and I’m in Los Angeles,” she says as she sits at the living room table of her hillside home in the Highland Park neighborhood. “Welcome.”

The women have joined Mykytyn for a virtual support group for white parents who have decided to walk the talk on supporting racially integrated schools. A mom in Houston says she’s planning to move her kids from a largely white school to one that’s 99 percent black and Hispanic. Another from Birmingham, Alabama, says she and her middle-class peers have had to learn to avoid coming across as “saviors” of their low-income school. Mykytyn mentions the readings she assigned to the group, which describe the double-edged sword of privileged parents who seek to improve neglected schools while introducing new disparities. “Maybe the main theme,” she says, “is that it’s all really, really complicated.”

In 2014, Mykytyn founded Integrated Schools, a grassroots organization that encourages white families to “deliberately and joyfully” take the first step toward making their local schools more racially and socioeconomically diverse. While organizations such as the Century Foundation and the National Coalition on School Diversity promote integration on the national level, Mykytyn’s group is focused on recruiting middle-class white parents—the very people who have historically resisted sending their kids to integrated schools. “We’re the ones who kind of made it all fail,” says Mykytyn, who has a doctorate in anthropology. “Really fixing it has to be on us.”

By several measures, America’s classrooms are becoming more divided. School districts have largely abandoned the court-mandated desegregation plans of the late 1960s and 1970s. In 2010, about 40 percent of black and Hispanic students attended schools where no more than 10 percent of students were white—a greater share than in 1980. Between 2000 and 2014, the percentage of public schools where nearly all the students are poor and black or Hispanic jumped from 9 to 16 percent. And separate remains unequal: Schools that serve mostly poor students of color tend to have fewer experienced teachers and less rigorous courses. They get less funding, and their facilities are more likely to be older and inadequate. When those same students attend integrated schools, test scores and graduation rates improve. As adults, they earn more and are healthier.

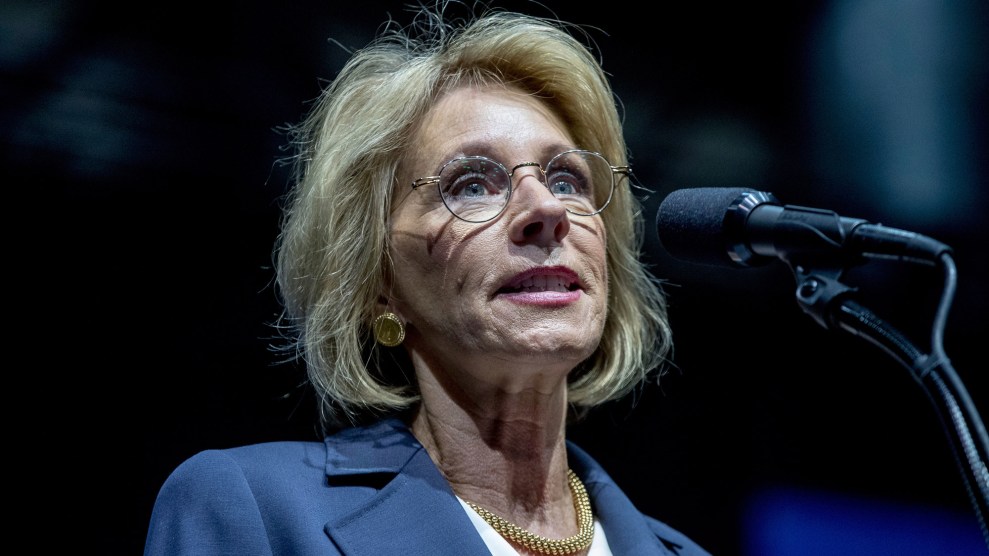

There’s also evidence that racially diverse schools don’t harm white kids academically and may make them more open-minded and creative thinkers. Yet when affluent white families do settle in diverse neighborhoods, they often opt out of local schools in favor of private, charter, or selective public schools. Under Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, a strong proponent of “school choice” and using tax money to fund private schools, these families may soon have even fewer incentives to support their neighborhood schools.

Despite these trends, some white parents, like Mykytyn, see their local schools as an important opportunity to pursue integration. Yet their good intentions can cause problems. Many enroll en masse, and some request that their kids are grouped together. They often refocus parent-teacher associations on fundraising, shutting out less wealthy parents. As their investments draw in more middle-class families, schools can become overenrolled, squeezing out poor students who would benefit from the new resources. Well-meaning parents often trigger a process of “school gentrification,” says Linn Posey-Maddox, the author of When Middle-Class Parents Choose Urban Schools. As their children’s schools become diverse and well funded, they can become more exclusive unless school districts step in and oversee the transition. “It shouldn’t just be left up to parents to bear the burden of integrating and equity,” she says.

Mykytyn saw a number of these challenges up close at her kids’ school in Highland Park, a historically working-class Latino neighborhood. About a decade ago, its inexpensive housing started to attract more white families, but the newcomers avoided the poorly rated public schools. Mykytyn formed a group of parents who pushed the district to create a program that mixed English- and Spanish-speaking students at Aldama Elementary School. Seven years later, the number of white students at Aldama has quadrupled, though it’s still less than 10 percent. The percentage of poor students has dropped from 91 to 72 percent. Most of the white and middle-class students are concentrated in the dual-language program, and their parents have a significant presence in the PTA. Some Latino parents quietly fret about the steady influx of white families. “I don’t feel them as a threat because I’m familiar with most of them,” says Adriana Reyes, whose daughters are in fourth and sixth grade. “But a lot of parents do feel like, ‘Oh no, they’re going to kick us out. They’re going to take over our school.'”

Yet the changes have also strengthened Aldama. The PTA has funded gardening and computer programs. Parents say their kids have formed friendships across race and class lines. And teachers have ramped up their expectations in the classroom, says Angelina Sáenz, a parent and kindergarten teacher who helped create the dual-language program. “Because of inherent racism in our system,” she says, “when white students are around, things get better.”

For integration evangelists like Mykytyn, confronting these sometimes messy realities is better than doing nothing. During the virtual meetup, a Harlem gentrifier admits she’s been “pretty awful” at joining the largely black and Hispanic community at her school. The woman from Richmond urges her to keep trying. “You are going to feel uncomfortable,” she says. “But being uncomfortable is a hallmark of doing the right thing.”