As the long line of cars, trucks, and more than two dozen charter buses pulled into dusty, makeshift parking lots in the high desert below California’s snowcapped Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains on Saturday morning, they were greeted by a National Park Service ranger. “Welcome to Manzanar,” she said. “It is very dry. Drink a lot of water.”

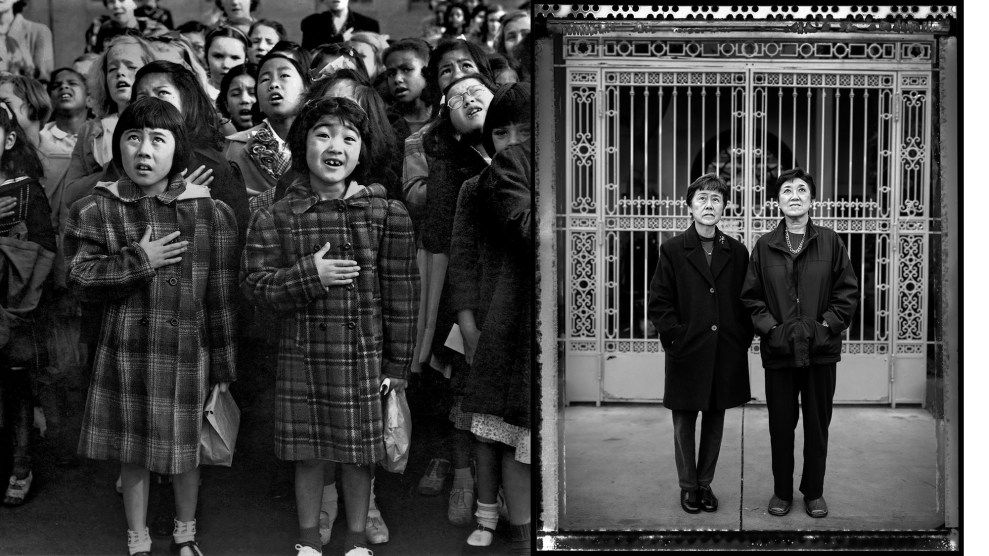

They’d descended on the remote Owens Valley, four hours north of Los Angeles, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066—President Franklin Roosevelt’s February 1942 decision to forcibly detain 120,000 Japanese Americans until the end of World War II. Manzanar War Relocation Center, as the facility was formally called, was one of 10 internment camps nationwide; at its peak, the 5,415-acre site held more than 10,000 people in army-style barracks behind barbed wire.

In the language of the Roosevelt’s order, these actions were taken to establish “every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense.” Approximately two-thirds of those incarcerated without due process were fully enfranchised American citizens by birth. The remainder were lawful permanent residents.

President Donald Trump’s harsh rhetoric about Muslims, Mexicans, and other immigrants has reignited scrutiny of this dark period in American history. Internment even made headlines in November when Carl Higbie—the former spokesman of the pro-Trump Great America PAC—cited American treatment of Japanese residents in WWII as an example of appropriate action to protect national security.

So perhaps it was no surprise that the 2,500 people who showed up as part of the 48th-annual Manzanar Pilgrimage on Saturday were a record for the event, according to the Park Service. The blowing dust, the whipping wind, and the beating sun all set an elemental tone for the day’s program—a not-so-subtle reminder how, as Manzanar Committee co-chair Bruce Embrey later would tell me, “there was a vicious, just despicable drive to make sure that these camps were sites of suffering. That the people here were going to be isolated psychologically and physically, far from civilian populations, in desolate areas intended to make people suffer.”

Though the camp was almost entirely disassembled after World War II—concrete slabs and the occasional piece of rusted metal are all that remain of the camp’s former living areas—the pilgrims visiting Manzanar walked past full-size reconstructions of the camp’s latrines, its mess halls, and its tar-paper barracks on their way to the day’s ceremony. Wooden Park Service signs marking the locations of long-disappeared structures—a recreation hall, an outdoor theatre, a pet cemetery, an elementary school—dotted the path.

Several people in the crowd wore shirts from various California-based Muslim organizations. Among them was Syed Hussaini, an organizer with CAIR’s Los Angeles chapter. Hussaini explained that, for the past few years, CAIR-LA has participated in the Manzanar Pilgrimage in order to keep alive the memory of internment—it is only briefly mentioned, if at all, in most schools—in the Muslim community.

“We have to stand very vigilantly, and make sure that we are upholding the tenants of democracy. If good people don’t do anything, this is what could happen again,” said Hussaini, who came to Manzanar on one of the three buses CAIR-LA chartered this year.

“When the executive order was signed back in the ’40s, only the Quaker community openly voiced dissent,” said Hussaini, echoing a point made a few minutes earlier by one of the event’s speakers. “But we have seen an outpouring of support from many other faith communities and many other civil rights organizations coming out to say that Trump’s words are not in keeping with American values, and will not stand.”

Preserving the memory of internment is the guiding mission of those who organized Saturday’s pilgrimage, as well as those who work to maintain and expand the facilities at Manzanar National Historic Site. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the generation of Japanese Americans born after internment began pushing for recognition and reparations. The Manzanar Pilgrimage, for example, began in 1969, kicking off decades of work to establish Manzanar as an officially recognized National Historic Site, which finally happened in 1992.

The theme for this year’s pilgrimage was “Never Again, to Anyone, Anywhere,” emblazoned in red text on black banners and T-shirts scattered throughout the event. That message, it seems, is resonating more than ever: In 2016, more than 105,000 people visited Manzanar, a record attendance year. A few employees noted that, since Trump’s election, there have been better, deeper conversations between Manzanar’s guests and those who work at the site.

A couple of hours after the ceremony concluded, several hundred people made their way to Lone Pine High School, about 10 miles south, for Manzanar at Dusk. In the school gymnasium, the Nikkei Student Unions at several LA-area colleges put on a three-hour program that spawn intergenerational conversations about their daytime experiences at the Manzanar Pilgrimage, and to spread the oral tradition of those who spent years confined in the camp.

After a spoken word performance that wove together FDR’s E.O. 9066 with Trump’s E.O. 13769, a.k.a. the travel ban, the 300 attendees broke into two-dozen randomly sorted small groups for an informal, hourlong conversation. Sprawled out on high school’s front lawn in the twilight shadows of the Sierra’s highest peaks, the small group I joined consisted of 10 people, the youngest in high school, the oldest in his 70s.

We listened to the grandson of a woman who lived at Manzanar relay one of her stories about the dust, and how she remembered seeing the outline of her sleeping body sketched out in her bedsheets when she got up each morning. We discussed why people remained quiet about their time in camps for years following their internment. And, by the end of our hour, we were sharing the history of our own personal names, comparing notes about whether our parents gave us a name from the old country or one considered more traditionally “American.”

“History is always relevant. But there are times when what’s happening in the world magnifies that relevancy,” said Alisa Lynch, the chief of interpretation at Manzanar National Historic Site, said to me after Manzanar at Dusk had concluded. “Our job is to share history, not to please whoever’s in office. We’re here to help people learn about the history, and if they want to make parallel connections, they’re free to. People see them. We don’t have to point them out.”