One night in May 2009, Jocelyn packed a backpack and left the ramshackle house in Naples, Utah, where she lived with her mom and two of her five siblings. She was six months pregnant—a condition that had caused the 17-year-old to drop out of high school and become alienated from her Mormon family. That night she’d broken up with her new boyfriend, who, though not the father, was her biggest source of support.

She planned to hitchhike 2,000 miles to Florida, where her dad lived, even though they hadn’t spoken in years. She only made it to a gas station a block away before she stopped, in tears. Aaron Harrison, a “Goth” 21-year-old, approached Jocelyn and asked if he could help. “I was a mess, I was crying, I didn’t know what to do,” she remembers. “I told him everything. I even told him about thinking of ending the pregnancy.” He asked if she wanted to go to his place nearby and talk.

Jocelyn (which is not her real name), a petite woman with wavy brown hair and a soft twang, told Harrison that her boyfriend had suggested an abortion could be caused by a punch in the stomach, and that they had even discussed resolving her pregnancy problem this way. So Harrison struck a deal with her. If he beat her up so she would miscarry, Jocelyn would give him the $150 she’d brought for her trip. If anyone asked, she’d say she had been sexually assaulted.

He was more than cooperative. Once inside his house, he punched her in the stomach, slapped her face, and bit her neck. Jocelyn says they also had sex, thinking it would help their cover story.

But things quickly got out of hand—”he hit me really hard”—and Jocelyn ran out of the house, shocked, bruised, and appalled by what they’d done. “I felt so sad for my baby,” she tells me. “I felt awful that I’d just agreed to any of it. But I also felt like a victim.” She called her mom and told her she’d been sexually assaulted. Jocelyn’s mom took her to the police station, where she was questioned by a detective. Jocelyn stuck with her story at first, but the cop kept questioning her, she says, well into the middle of the night. After she finally confessed, the police took her to the hospital. Her unborn baby was alive.

The next day, Jocelyn was arrested. “The county attorney said, ‘Take her straight to detention,'” she says. “‘This is insane, this is unacceptable, this is attempted murder.'” Jocelyn was moved to Split Mountain, a juvenile center, and charged with solicitation of murder, which would have been a felony if she were an adult. Harrison was also arrested and charged with attempted murder.

“That was the worst moment of my life,” Jocelyn, now 25, tells me from her home in Vernal, Utah, with two young children cooing behind her.

During his presidential campaign, Donald Trump said women who end their pregnancies ought to face “some form of punishment.” He was met with an onslaught of criticism, even from anti-abortion groups, which characterized his position as “completely out of touch with the pro-life movement.” Before efforts to decriminalize abortion began in the late 1960s, women were rarely prosecuted for attempting to access the procedure. Anti-abortion advocates argued then, as most do now, that women, like their fetuses, were victims. After Trump’s comments, March for Life issued a press release with the headline “No Pro-Life American Advocates Punishment for Abortion.” Jeanne Mancini, the organization’s president, went further, saying, “Being pro-life means wanting what is best for the mother and the baby. We invite a woman who has gone down this route to consider paths to healing, not punishment.”

Trump quickly walked back his statement; doctors, he said, not women, should be punished. But his remarks exposed a tension at the heart of the pro-life legal movement: How can abortion become illegal without punishing the women who seek them? The question has come into greater relief over the last several decades, as state and federal laws have evolved to regard fetal deaths as potential homicides. With Republicans now in control of federal judicial nominations and most statehouses, growing gaps in the abortion rights landscape seem likely to drive more women to self-abort, just as several high-profile cases have shown prosecutors willing to bring charges against those who take desperate measures to end their pregnancies.

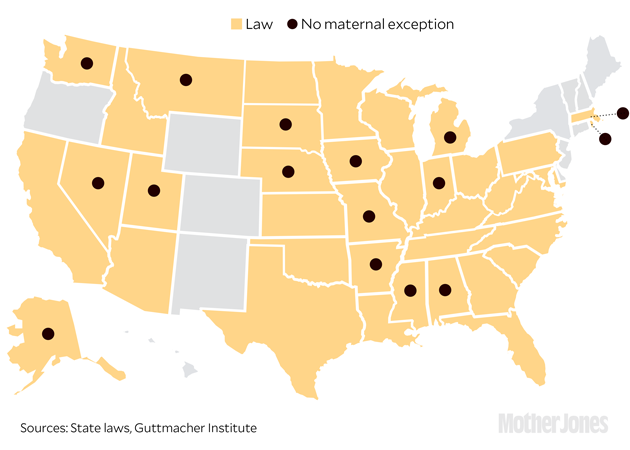

Mother Jones has identified at least two dozen cases since Roe v. Wade in which women faced investigation or prosecution for a self-induced abortion, according to a review of news reports, scholarly articles, and court documents. But Jill E. Adams, who leads the Self-Induced Abortion Legal Team at the University of California-Berkeley, says the real number is unknown. In the eight years following Jocelyn’s arrest, eight women, almost all in the Midwestern or Southern United States, have been investigated, charged, or prosecuted for trying to end pregnancies, or for being suspected of doing so. About half the women charged since Roe, including Jocelyn, were accused of homicide, manslaughter, or a related crime—charges enabled by “fetal homicide laws,” which are on the books in 38 states and make killing a fetus a crime.

Fetal homicide laws are the result of a two-pronged strategy that anti-abortion groups adopted after their 1973 Supreme Court defeat in Roe: They pushed state laws that made abortions harder to get and expanded the legal rights of fetuses so that the public, and eventually the courts, would begin to regard the unborn—no matter what stage of development—as children. Advocates started by working to define life as beginning at conception in nonabortion contexts—property or contract law, for instance.

But criminal prosecutions of anyone who killed a fetus soon followed. In one of the earliest such cases, attorneys for Americans United for Life, the nation’s most influential pro-life legal group, fought to get an Illinois man prosecuted for murder after he shot a pregnant woman, allegedly killing her unborn child. (He was found not guilty; a judge was not convinced his bullet had killed the fetus.)

In 1984, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that the state’s vehicular homicide statute should apply to a driver who crashed into a pedestrian and killed her eight-and-a-half-month-old fetus. In 1986, a year after the Minnesota Supreme Court held that the state’s vehicular homicide law shouldn’t apply to fetuses, the Legislature stepped in to pass a fetal homicide law starting from the moment of conception.

These rulings and laws represented the first cracks in the so-called “born alive” rule, which required a child to be alive and out of the womb before it could be considered the victim of a homicide; the standard had been used by virtually every jurisdiction in the United States for more than a century. In 1987, Clarke Forsythe, a new Americans United for Life lawyer, released a paper (paywall) with model fetal homicide legislation aimed at further unraveling the born-alive standard. He led a team of young pro-life lawyers and advocates who argued that in an era with technology that is capable of determining the precise status of a fetus in utero and even, in rare occasions, the cause of death, the born-alive standard was arcane and immoral. “Modern medicine made that rule obsolete,” Forsythe told me.

By 1994, 17 states had fetal homicide laws on the books. Mary Ziegler, a legal historian and author of the book After Roe, says the particular genius of fetal homicide laws was “you could convince lawmakers to pass them even if they were uneasy with the pro-life movement. They were personhood laws, but they didn’t apply to abortion.”

Mountain ranges and hills surround Uintah County, where Jocelyn grew up. Giant dinosaur statues are scattered throughout the area, an homage to nearby paleontology digs. For decades, many of Uintah’s 38,000 mostly Mormon residents worked extracting oil and shale gas. Jocelyn and her five siblings grew up in Jensen, with a population of fewer than 500, in the northern part of the county. Her mother waitressed and her father worked as a carpenter until a back injury forced him to stop. When Jocelyn was 10, he left without a goodbye. Jocelyn’s mom struggled with addiction, and eventually she moved her family into a small condemned home, with no running water or electricity, on her parents’ property in nearby Naples.

By the time she was in 11th grade, Jocelyn, fed up with her mother’s problems and the family’s living situation, moved into a small apartment in Naples, a town lined with fly-fishing shops, industrial facilities, and motels. She was working toward a welding certificate in high school and had started dating a senior she met in class. Then she found out she was pregnant. She knew her ex was the father and her new boyfriend wouldn’t raise someone else’s kid.

“I kind of spiraled,” Jocelyn remembers. “I started to show, and then I was embarrassed to go to school, so I dropped out.” She moved back in with her mother and brothers. Lights and space heaters were powered by extension cords running from her grandparents’ house. If Jocelyn had to go to the bathroom after the doors were locked for the night, she’d have to pee outside.

She struggled with what she should do, weighing the pressure she felt from her new boyfriend to have an abortion. “I didn’t think abortion was wrong or right or indifferent. I was just a 16-year-old with a boyfriend who was the closest person to me at that time.” Utah’s nearest abortion clinic was about 170 miles away in Salt Lake City, and Jocelyn convinced her mom to drive her the three-plus hours across mountains and snow and pay several hundred dollars to end her pregnancy. According to court records, clinicians told her an abortion would be impossible because she was too far along. At the time, state law banned abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy; Jocelyn does not recall being so far along. (Later that year, the Legislature moved the limit to viability, usually considered 24 weeks.)

On the ride home, Jocelyn remembered the ultrasound and hearing the tiny heartbeat; she worried that abortion wasn’t for her. Adoption was one option, but she couldn’t imagine giving the baby to an anonymous couple. After being turned away from the clinic, Jocelyn swallowed a handful of pills in a failed suicide attempt. “I tried to just get rid of us both. And when I did survive, there was even more disappointment,” she says. “There were no other options. There was nothing else.”

Following success in the states—26 had passed fetal homicide laws by the end of the ’90s—then-Rep. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) and other congressional Republicans introduced a bill in September 1999 that would make it illegal to injure or kill a fetus in the commission of a federal crime. Their proposal, called the Unborn Victims of Violence Act, mirrored state laws, with one key difference: Most state laws only protected fetuses starting from some point after the first trimester, but the federal bill sought to cover fetuses from conception. Democrats argued that the measure encroached on abortion rights, and President Bill Clinton threatened to veto it. As a countermeasure, Democrats, led by Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), introduced a “single victim” bill that increased federal punishment for harm done to a pregnant woman, without mentioning her fetus. Neither House bill made it over to the Senate, and the same battle played out for the next three and a half years.

Then, on Christmas Eve in 2002, Laci Peterson—supposedly on a fishing trip with her husband, Scott—went missing. She was eight and a half months pregnant with a son she’d named Conner. Scott’s odd behavior quickly made him the focus of the investigation. When a mistress came forward, three months of tabloid coverage ensued before Laci Peterson’s body washed up on the shore of the San Francisco Bay. Scott Peterson was eventually convicted of murder. At his sentencing, Laci’s mother read a statement to the court, written in Conner’s voice. “Daddy,” Sharon Rocha read, “why are you killing Mommy and me?” Scott was sentenced to death.

Congressional Republicans had found their rallying cry. In 2003, while the Peterson case was ongoing, Sen. Mike DeWine (R-Ohio) and Rep. Melissa Hart (R-Pa.) introduced the Unborn Victims of Violence Act yet again, now dubbing it Laci and Conner’s Law. Rocha wrote to the bill’s sponsors to thank them, adding that she hoped for a future where “no surviving mother, grandmother, or other family member is ever again told, ‘We’re sorry, but in the eyes of the law, there is no dead baby.'” On March 25, 2004, the Senate passed the bill in a 61-38 vote.

At the signing ceremony a week later, President George W. Bush praised Laci and Conner’s Law: “Any time an expectant mother is a victim of violence, two lives are in the balance, each deserving protection, and each deserving justice.”

With the federal law in place, fetal homicide legislation gained new momentum. In several states, legislators enlisted a survivor whose pregnancy had ended after an attack, or a deceased woman’s family, to become the public face of their campaign—Alexa’s Law in Kansas, for instance, or Ethan’s Law in North Carolina. Americans United for Life and other pro-life organizations pointed out that domestic violence can spike during pregnancy and argued that fetal homicide laws could deter abusive fathers. With the federal Unborn Victims of Violence Act as a model, the newest state fetal homicide laws protected fetuses from the moment of conception; several states with laws that previously only applied after viability amended them to start earlier in pregnancy.

Unsurprisingly, abortion rights advocates argued the measures were part of a broader push to roll back Roe, this time by pitting women against the fetuses they’re carrying. “There is no way the state can protect embryos and fetuses separate from the woman without subtracting the pregnant woman,” says Lynn Paltrow, the founder of National Advocates for Pregnant Women, warning that if people come to see fetuses as human beings who can be murdered by an angry boyfriend, they will extend that idea to abortions sought or performed by the woman herself.

But pro-life groups dismissed such criticisms, noting that most fetal homicide laws have exceptions for abortion or other actions (intentional or otherwise) a woman might take to end a pregnancy. “Pro-life legislators and pro-life leaders do not support the prosecution of women and will not push for such a policy,” Forsythe, now the acting president of Americans United for Life, wrote in 2010.

In June 2009, a month after her arrest, Jocelyn skipped trial and was advised by her public defender not to challenge the charge of solicitation of murder. She was sentenced to detention until age 21 and transferred to a juvenile secure facility south of Salt Lake City.

After nearly three months behind bars, she went into labor in August and was transported to a hospital in handcuffs and leg shackles. After giving birth, she was allowed to hold and breastfeed her new daughter while locked to the bed. Leaving her baby at the hospital “was the hardest part,” Jocelyn remembers. “Once they start moving and you watch them come out of you, you love them—they are you. And you can’t even fathom life without them. And then they’re gone. And you’re alone again. And people looked at me and told me I deserved it.” Her daughter, born with a clean bill of health, was adopted by Jocelyn’s aunt, who lives two hours from Naples.

Meanwhile, Jocelyn and her mom found a new lawyer, Richard King, who petitioned the juvenile court to reverse her plea deal, arguing that she had broken no law and that her previous lawyer, who had also represented her ex-boyfriend after he was charged with producing pornographic pictures of her, had a conflict of interest. In October 2009, a juvenile court judge, Larry A. Steele, agreed to reverse the deal.

The judge may have rescinded Jocelyn’s plea deal, but she still had to face the state’s charges in a new trial. King’s defense focused on the text of Utah’s 2009 fetal homicide law, which defined homicide as a person causing the death of another person, “including an unborn child”—except when that death is the result of an abortion. He argued that Jocelyn’s actions had been part of an abortion attempt and demanded the charges be dismissed. Steele agreed: “No one should interpret this ruling to mean this court thinks the minor’s conduct was justifiable. What the minor did was terribly wrong. However, only the legislature can determine whether such conduct as set forth here should be criminal.” The state appealed the decision, but Jocelyn was free.

Days after her release, Carl Wimmer, an ex-cop who was then a prominent Mormon state representative, told reporters that he was going to close the “loophole” that Jocelyn’s lawyer successfully used in her defense: “Abortion and right to life is the top issue for me, and it is something I feel very passionate about.” A month later he introduced a new fetal homicide bill that redefined abortion as a medical procedure performed in the care of a physician. “[Jocelyn] revealed an extreme weakness in the law, that a pregnant woman could do anything she wanted to do—it did not matter how grotesque or brutal—all the way up until the date of birth to kill her unborn child,” Wimmer told The Nation. He boasted that his bill would make Utah the only state to “hold a woman accountable for killing her unborn child” in cases other than a medical abortion. In March 2010, less than a year after Jocelyn’s arrest, Wimmer’s bill became law.

While Aaron Harrison pleaded guilty in 2009 to attempted murder, Jocelyn’s case climbed to the state’s highest court. In December 2011, the Utah Supreme Court sided with the state, reversing the juvenile court’s decision to dismiss the charges. She was once again at square one, this time under the shadow of the new and more punitive law. Though the law wouldn’t apply to her, a draining and very public trial still loomed. She wanted out. Jocelyn pleaded guilty to solicitation of a crime, a second-degree felony. The charge was reduced to a misdemeanor after she completed 60 hours of community service.

Thus far, Utah is the only state that has strengthened a fetal homicide law in direct response to a self-induced abortion. But several recent cases have shown there are prosecutors ready to use the laws to punish women who perform their own abortions. The methods can be desperately brutal. Women have been targeted for shooting themselves, stabbing their bellies, and drinking toxic levels of herbal tea. In 2015, a Tennessee woman named Anna Yocca was charged with attempted first-degree murder after allegedly using a coat hanger to try to end her pregnancy. She took a plea deal this January after spending a year and a half in jail. In 2009, Indiana amended its 1998 fetal homicide law after a robber shot a pregnant bank teller in the abdomen. In 2013, prosecutors used the law against Purvi Patel, who went to the emergency room after taking pills she bought online to end her pregnancy and experiencing heavy bleeding. A pro-life doctor turned her in to the police. After three years behind bars, Patel was convicted of feticide and neglect of a dependent. She was sentenced to 20 years before the state’s appeals court overturned the feticide conviction last September, accusing prosecutors of “unsettling” overreach.

“I don’t think any of us have any sense of how common home abortion is right now,” says Adams. But surveys sampling the approximately 900,000 women who get clinical abortions each year help give a rough sketch. A national study found that about 2.6 percent of patients reported taking drugs, herbs, or vitamins before seeking an abortion. A 2014 study in abortion-hostile Texas found that 7 percent of patients surveyed in 2012 said they’d done something in the hopes of having a miscarriage before coming in. In 2011, after nearly 100 new state-level abortion restrictions had been enacted, a New York Times analysis found that Google searches for “how to have a miscarriage” or “how to do a coat hanger abortion” had jumped 40 percent compared with the year before. The state with the highest rate of searches, Mississippi, has just two abortion providers. The Times noted that a few hundred searches occurred nationwide for information on inducing abortion by being punched in the stomach.

Having an abortion at home, without the supervision of a physician, is not necessarily unsafe. Misoprostol, a prescription drug in America that is given over the counter in other countries, effectively ends upward of 88 percent of pregnancies within the first 12 weeks. When taken with mifepristone, a prescription-only drug usually dispensed under supervision of a doctor, the effectiveness jumps to over 95 percent. But if the Trump years bring further restrictions to choice, the number of women looking to end a pregnancy outside of clinical care seems certain to increase. Even safe drugs—whether purchased from online dark markets or provided by abortion activists—can be misused or abused or fail, sending women to the emergency room to face not only life-threatening complications, but prosecutors backed by fetal homicide laws. “In the new political reality of 2017,” Adams says, “we could foresee an emboldened anti-choice movement that places women who end their own pregnancies in the bull’s-eye.”

Jocelyn never left the Uintah Basin. When I visit, she takes me on a drive up to Split Mountain, the namesake of the detention center she once called home. A massive cliff face that hulks over the Green River, it’s been a place of solace and reflection for Jocelyn over the last eight years. After being released, she searched for structure and found the Jehovah’s Witness faith and a husband who shares it. Her religious convictions have changed her views on abortion: No longer ambivalent, Jocelyn now believes it is wrong. She’s not in touch with the daughter she birthed while incarcerated. In her community, she can’t talk about her own abortion attempt for fear of judgment. For her husband, an auto mechanic in Naples, the decisions Jocelyn made as a teenager are referred to just as “her past.”

With the youngest of their two daughters, not yet a year old, in tow, we walk to the base of Split Mountain, where our figures are dwarfed. Though her views on abortion have changed, Jocelyn remarks that women who end their own pregnancies aren’t “heartless.” She wishes she’d made a different choice that night. But she understands why she didn’t. “It was the fact that I was left up to my own options, which were…nothing,” she says. But she doesn’t judge other young women. “I know being put in that situation, how desperate women can be.”