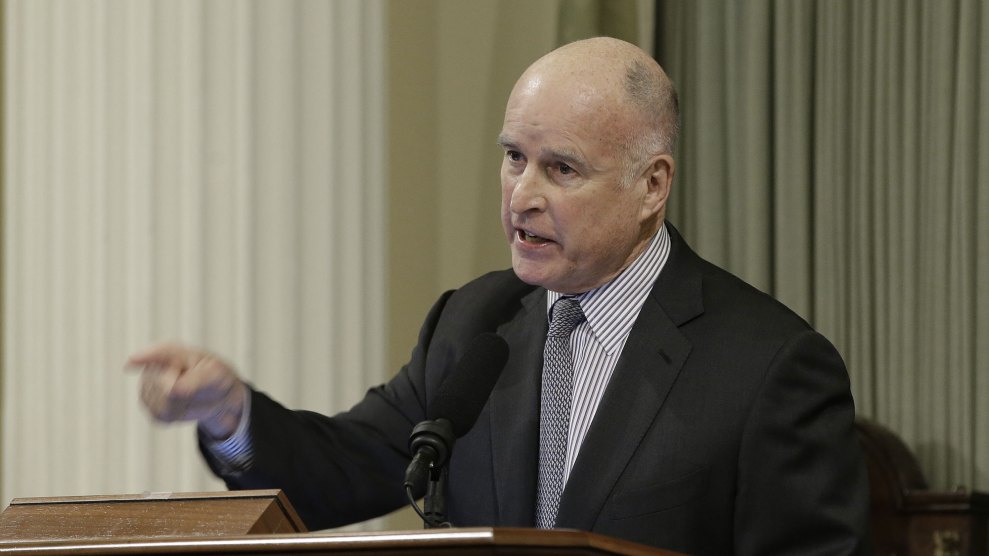

CaesarsaGuru/Getty

California legislators will vote Thursday on a gas tax and other vehicle fees proposed by Gov. Jerry Brown that would raise $52 billion over ten years to fund repairs to the state’s crumbling roads, bridges, and public transit systems. Though the vote once seemed like a slam-dunk in the this deeply blue state, Brown is facing likely defections from moderate members of his own party who are concerned about the tax’s effects on farmers and suburban commuters.

“Don’t blow it guys,” Brown said at a Tuesday press conference in the Inland Empire district of Democratic state Sen. Richard Roth, one of the last holdouts on the bill. “You’re going to be driving on these damn roads. Fix them now, or we may never get them fixed. I don’t know what opponents expect—the tooth fairy to fix the roads?”

The bill is shaping up to be a key test of Democratic unity. It must overcome a California requirement for a two-thirds supermajority to enact tax increases. Though Democrats hold a narrow supermajority in both houses of the legislature, Republicans are unanimously opposed to the bill, which means that a single Democratic defection can kill the proposal.

The defeat of the bill would be a major blow to Brown, 78, who has positioned his state as a bulwark against right-wing policies and bureaucratic incompetence of the Trump administration. Brown’s proposal to fund infrastructure though increases in the state’s gas tax resembles the approach proposed by Democrats in Congress, where Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Oregon), the ranking member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, is pushing a similar plan known as the “Penny For Progress Act.”

Raising taxes to fund infrastructure isn’t necessarily a partisan issue. If the California bill passes the state would join 17 others—half of them controlled by Republicans—that have increased gas taxes since 2013. “I have a fair amount of rank-and-file [Republicans in Congress] who like the proposals that I’ve put out there,” DeFazio told Mother Jones. Yet in California, many moderate Republicans have lost their seats to Democrats, leaving behind a more conservative and united GOP opposition.

California already has some of the highest gas taxes in the country, but the falling price of gas, increases in fuel efficiency, and the advent of hybrid and electric vehicles has crimped revenues in recent years, contributing to an estimated $135 billion backlog in road and bridge repairs. According to the Department of Transportation, California’s roads are among the worst in the country, with 68 percent in “poor to mediocre” condition—costing state motorists $13.9 billion annually in extra vehicle operating costs and repairs. Brown’s bill would move to plug the funding gap with a 12-cent per gallon increase in the gas tax, new taxes on diesel, a $100 annual fee on electric vehicles, and higher vehicle registration fees.

To win support for the bill’s diesel tax among rural and moderate Democrats, Brown included a provision that would give the trucking industry more time to comply with antipollution regulations—angering environmental and health advocates. One Democrat, Sen. Connie Leyva of Chino, has withheld her support for the bill due to concerns over how it will affect air pollution.

Brown, who previously served two terms as governor starting in the late 1970s, has a reputation as both a fiscal moderate and an infrastructure hawk. His father, California Gov. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Sr., oversaw the construction of massive post-war infrastructure projects such canals, aqueducts, and university campuses. Brown has continued that legacy with projects such as a pair of $15.7-billion water tunnels under the Sacramento Delta and a $64-billion high-speed rail line connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco. Both projects are being financed with bonds and user fees rather than new taxes.

Californians have often shown a willingness to tax themselves in exchange for better services, though the issue tends to cleave along geographic lines. In November, 70 percent of Los Angeles voters approved a permanent sales tax increase to fund a major expansion of the county’s public transit service. Yet voters in the less affluent, more rural Central Valley are more fiscally conservative. A Survey USA poll released last week found that overall only 37 percent of Californians support raising the gas tax to pay for transportation projects, 44 percent oppose the idea, and 19 percent are undecided.

In Washington, where Trump has promised $1 trillion in new infrastructure spending, many Republicans are pushing an alternative approach that would eschew tax increases for “public-private partnerships.” House Speaker Paul Ryan and a faction within the Trump administration led by billionaire leverage buyout specialist Wilbur Ross, Trump’s Commerce Secretary, want almost all of the spending to come from tax credits given to private investors who underwrite infrastructure projects such as toll roads. Ross argues that $137 billion in tax credits over ten years could spur $1 trillion in investment, meeting Trump’s campaign pledge. But even many conservative economists say the approach doesn’t hold water.

“I don’t think that is a model that is going to be viewed as successful or that you can use it for all of the infrastructure needs that the US has,” Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the center-right American Action Forum think tank, told the Associated Press. It would only work for projects that generate tolls or user fees, he said, and even then, might just reward investors for projects that would have been built anyway.

Brown continued to push hard for the bill on Wednesday. “I know there are a couple of people who are worried about voting for taxes,” he said during a rally on the Capitol steps. “This is a fee, a fee for the privilege of driving on our roads that the people pay for, and we’ve got to keep paying for them. Otherwise, they are not going to work for us. It’s just that simple.”