jc_design/iStock

Shortly after Donald Trump won the election, Todd Rathner, a prominent gun rights lobbyist, said gun owners were eager to “go on the offense at the federal level.” Among their top priorities was national reciprocity legislation: a law guaranteeing that people with concealed-carry permits from one state could take their guns into any other state, even if that state had stricter limits on carrying concealed weapons. Sure enough, on the first day of the new session of Congress, Rep. Richard Hudson (R-N.C.) introduced the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act of 2017.

Hudson, a member of President-elect Trump’s Second Amendment Coalition, isn’t the first lawmaker to introduce a national reciprocity bill that would effectively override many existing state gun laws. But his bill is broader than its predecessors. Gun advocates have typically couched the need for reciprocity as a convenience to travelers who must contend with a “patchwork” of gun laws while on interstate road trips. Hudson’s bill, however, goes far beyond making travelers’ concealed-carry permits portable across state lines. It would also force states to allow residents with a concealed-carry permit issued in another state to pack heat. Additionally, it would allow gun owners from states that do not require concealed-carry permits to carry weapons in states that do require permits.

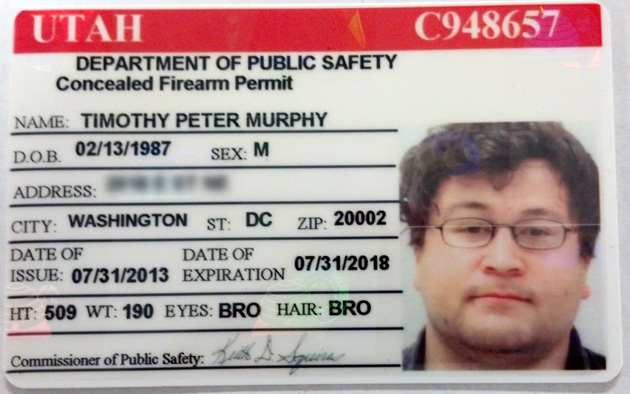

These provisions are significant. Many previous reciprocity bills would not allow residents of permit-free states to carry in states with stricter policies. Moreover, Hudson’s bill includes a loophole for gun owners who can’t obtain a concealed-carry permit in their own state. “Under Hudson’s bill, a California resident who cannot get a concealed-carry permit in California can easily get one from Utah, and then carry guns in California without ever setting foot in Utah, and not for some short duration like a tourist stay, but for the rest of his life and every day,” explains Adam Winkler, a law professor at the University of California-Los Angeles. “The real impact of the Hudson bill is not to protect interstate travelers. It’s to require states with restrictive concealed-carry policies to allow their own residents to carry guns.”

Anyone can get a Utah-issued concealed-carry permit by taking a gun safety class certified by the Utah Bureau of Criminal Identification. (Two-thirds of people with Utah concealed-carry permits live outside the state.) Getting a Virginia permit is even easier: Answer 15 of 20 questions correctly after taking an online course and you’re set. Applicants get four attempts to pass. Nine states already have “constitutional carry” laws that allow carrying a concealed gun without any training or permit. Forty states recognize some or all concealed-carry permits from other states.

Trump—who has said he sometimes carries a concealed weapon—has called for making concealed-carry permits like driver’s licenses, which are valid nationwide. He said concealed carry is “a right, not a privilege.”

Aligning with the belief among pro-gun advocates that “gun-free zones” facilitate mass shootings, the new bill also would override the Gun-Free School Zones Act, which makes it a federal crime to carry a gun in a school zone. This is in keeping with Trump’s campaign promise to “get rid of gun-free zones on schools.” Last January, he suggested he would sign legislation that would undo any restrictions on guns in schools: “My first day, it gets signed, okay? My first day. There’s no more gun-free zones.”

On Wednesday, the National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative Action came out in support of the Hudson bill, applauding it as “a much needed solution to a real problem for law-abiding gun owners.” Chris Cox, the executive director of the NRA-ILA, framed the bill in terms of “the fundamental right to self-defense while traveling across state lines,” but did not address its wider implications. “Let’s face it—tourists carrying their guns across state lines is not the biggest issue even for gun advocates,” Winkler says. “What they really oppose are restrictive concealed-carry policies in places like California, New York, and Maryland.”

Lindsay Nichols, a senior attorney at the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, believes the new reciprocity bill may pose a constitutional challenge to states’ long-standing authority to protect their citizens by regulating guns. “This removes the protections that the states have provided to their citizens,” she says. “It’s a really radical notion, and there are some questions about whether the federal government can deprive states of that authority.”

Previous efforts to pass national reciprocity legislation have failed. In 2013, a more moderate bill was voted down narrowly in the Senate. Nonetheless, Nichols predicts, “it’s not going to be easy for them to pass this.” She expects congressional Democrats to “toe the line” against the measure. On Monday, a week after Hudson introduced his bill, Chris Cox admitted on NRATV that getting national reciprocity will be no easy task, but told viewers that by engaging supporters and keeping pressure on the Senate, “we have a real opportunity.” Winkler foresees a fight, especially since the national reciprocity bill is a major item on the NRA’s wish list. “For the last 30 years, the NRA has led a major push to loosen concealed-carry laws,” he says. “There are a few holdouts that have resisted the NRA. Hudson’s bill is designed to win that final battle.”

This post has been updated.