Eric Risberg/AP

For all of his focus on industrial workers in the Rust Belt and his dire warnings about America’s inner cities, President-elect Donald Trump hasn’t had much to say about his plans for those in the deepest levels of poverty—including America’s homeless. And that—along with his recent choice of Ben Carson as Housing and Urban Development secretary—is making advocates across the country worried.

For the last six years, homelessness in America has been on the decline, thanks in part to improved federal, state, and local coordination of homeless services and increased investment in permanent supportive housing, rapid rehousing, and rental assistance programs, particularly for veterans. Since 2010, veteran homelessness dropped 47 percent; meanwhile, the number of chronically homeless individuals and families with children fell by more than 20 percent.

But advocates hear Trump’s calls to cut taxes and rein in government spending and are reminded of the 1980s, when drastic cuts in federal funding for low-income housing and social services set off a homelessness crisis. “We’ve never really recovered from those hits,” says Maria Foscarinis, executive director of the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty.

Trump’s so-called “penny plan” would cut 1 percent of government spending each year to pay for part of his proposed tax cuts. A fact sheet on Trump’s campaign website noted that defense and entitlement programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, would remain untouched, leaving education, environmental, health, and housing programs up for grabs. It’s unclear how much specific programs would be slashed, but the end result could be substantial: A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report in September noted that the proposed cuts would slice $150 billion from the federal nondefense discretionary budget by 2026, 37 percent less than what the government spent in 2010.

The federal government allocated at least $5 billion toward addressing homelessness in 2016, with 89 percent of funding split among the Department of Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, and Veteran Affairs. (The Obama administration proposed an additional 11 percent in its 2017 budget and an additional $11 billion over the next decade toward a permanent housing program for families with children who are homeless.)

Nearly half of roughly $5 billion in federal funding—geared toward supportive housing, rapid re-housing, and emergency shelter programs—is distributed in grants to states, communities, and nonprofits. So when there are cuts to funding at the federal level, the pool of money distributed to cities and counties becomes smaller. If Trump goes ahead with the penny plan and ends up curbing housing programs like Community Development Block Grant program or Section 8 housing vouchers, “we could see really devastating effects,” says Diane Yentel, the president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. She added: “At its core, homelessness is about a lack of access to affordable housing. Ending homelessness is about increasing and expanding affordable housing solutions.”

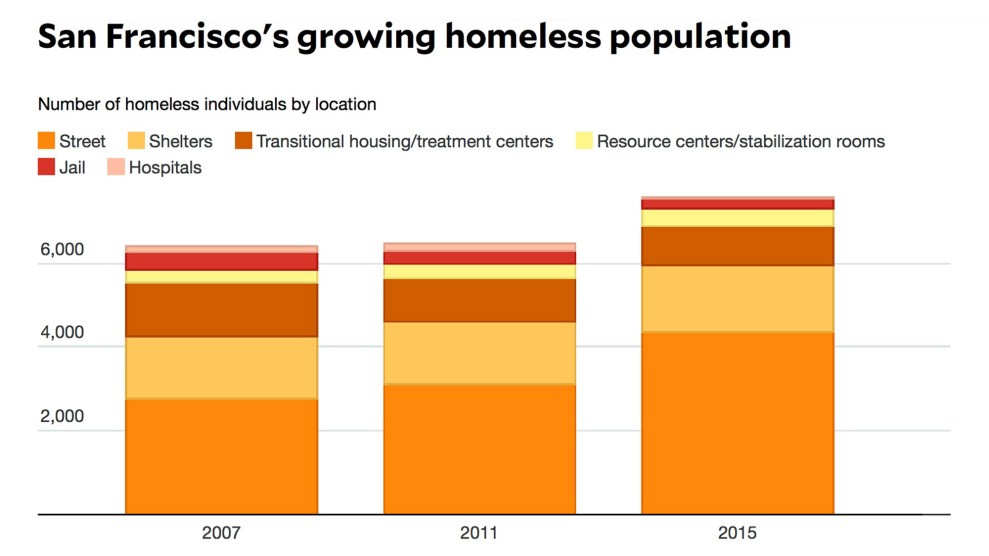

For the places that have seen homelessness rise over the past years—mostly West Coast cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle—the threat of further cuts is particularly worrisome. Take Trump’s pledge, for example, to cut off funding from “sanctuary cities” that limit cooperation with federal immigration officials. San Francisco gets $38.5 million in federal funds to spend on sheltering and housing homeless people (Its new homelessness department has an overall budget of $224 million). Seattle Mayor Ed Murray told the Seattle Times he predicted cuts that could “worsen what happens with the homeless and the addiction crisis we see in this country”; of the $85 million in federal money the city spent last year, $11.5 million went toward homelessness programs.

On top of the potential spending cuts, there’s the Republican promise to repeal Obamacare. For America’s poor, that could spell an end to the ACA’s Medicaid expansion program. Funds from Medicaid reimbursement have been used to support services for the chronically homeless who live in permanent supportive housing. Those services, according to Nan Roman, the president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, can help cut down on pricey emergency room visits.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council noted in a letter to advocates that while Congress may introduce repeal legislation quickly, the changes would likely not go into effect for another year or two. The council warned that if Congress moves forward with ending Medicaid expansion and replace it with state-issued block grants, “states will not likely have enough funds to pay for basic care, let alone for ‘extras’ like case management, housing assistance, or outreach. Such changes would seriously jeopardize the services that currently support people in housing and medical respite care, as well as limit the much-needed expansions of these programs.”

Municipalities around the country, then, are preparing for the worst. Jeff Kositsky, director of San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, told KQED’s Forum that the city’s permanent supportive housing would be secure. Still, he said, the city is working on contingency plans if federal funding is pulled.

“Oftentimes I hear people talking about homelessness as individuals failing to fit into the system. I really just see it as the system failing to meet the needs of individuals,” Kositsky said, adding: “So when our federal government stopped investing in low-income housing is when we saw this increase in homelessness and all the devastation that goes along with it. The mental-health issues, the substance abuse, the cycling in and out of programs, and really abject poverty—I directly connect [them] to our federal government’s failure to maintain a sensible housing policy.”