Rep. Cathy McMorris Rogers with Donald TrumpMike Segar/Reuters via ZUMA

On Friday the Wall Street Journal reported that Donald Trump has chosen Washington Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, chair of the House Republican Conference, to be his secretary of interior. The Interior Department is responsible for three-quarters of the nation’s public lands, and includes under its umbrella agencies like the National Parks Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the US Geological Survey, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Bureau of Reclamation—all which are on the front lines of the fight against climate change.

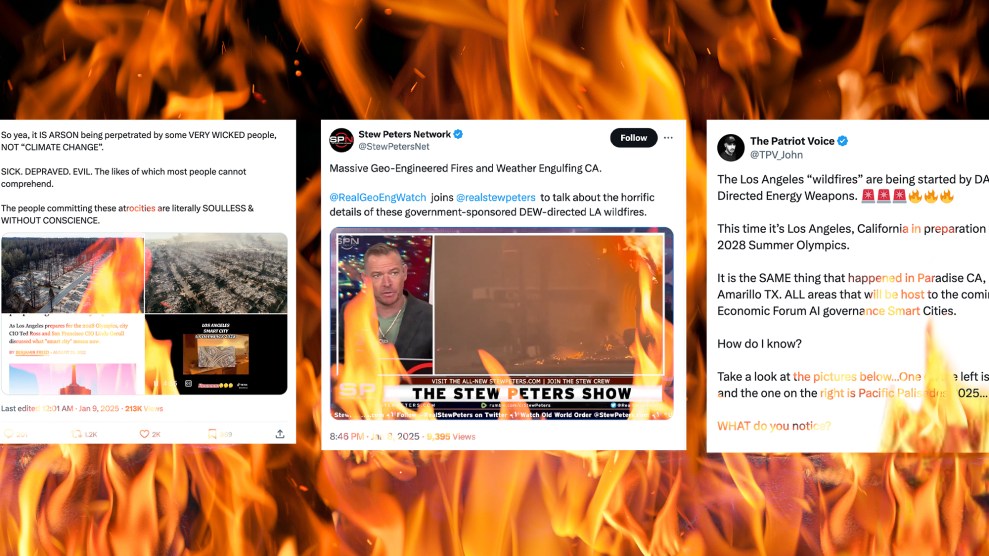

But if her record in Congress is any indication, don’t expect McMorris Rogers to make climate science or conservation a priority. In 2008, after Al Gore earned a Nobel Peace Prize and an Oscar for An Inconvenient Truth, she dismissed the former vice president’s warnings about global warming. “We believe Al Gore deserves an ‘F’ in science and an ‘A’ in creative writing,” she joked.

One year later, McMorris Rodgers sang a slightly different tune, telling a group of students from her district that “we should be taking steps to reduce our carbon emissions”—but that’s been the extent of her climate awakening. In 2010, she earned plaudits from the Koch brothers-backed Americans for Prosperity for opposing a cap-and-trade carbon-pricing system aimed at reducing emissions. In 2011 she voted three times against a resolution acknowledging that “climate change is happening and human beings are a major reason for it.” More recently, she co-sponsored the House bill to prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency (which is not part of Interior) from regulating carbon emissions; EPA carbon regulations form the core of President Barack Obama’s climate policy.

McMorris Rodgers has explicitly voted against letting the interior secretary consider climate change when setting policy. In 2014, while supporting legislation designed to protect hunters’ access to public lands, she opposed an amendment stipulating that “nothing in this Act limits the authority of the Secretary of the Interior to include climate change as a consideration in making decisions related to conservation and recreation on public lands.”

Even the firsthand effects of climate change on her district have done little to spur the congresswoman to action. When forest fires swept through eastern Washington in August, the state’s Democratic governor, Jay Inslee, argued that the fires, aided by tree-killing bugs and dry conditions, were a problem that would only get worse due to climate change—a position shared by the US Forest Service. McMorris Rodgers declined to make that connection when asked by reporters about Inslee’s comments, instead urging authorities to simply focus on “better forest management.”

McMorris Rogers, who has a 4 percent lifetime rating from the League of Conservation Voters, has taken concrete steps to curb the power of the department she’s now set to run. She’s repeatedly backed legislation that would limit the president’s authority to protect public lands under the Antiquities Act, which Obama and his predecessors have used to create marine sanctuaries and to set aside large chunks of the West as national monuments. (The impetus for the most recent push was Obama’s creation of Basin and Range National Monument, to be run by the Bureau of Land Management, in central Nevada.) She also backed a proposal to loosen environmental laws in national parks and wildlife refuges within 100 miles of the US–Mexican border. That’s not a good sign for fragile desert ecosystems—but it might come in handy when construction starts on Trump’s wall.