One evening in early May, Sen. Ben Sasse sat at his home on the banks of the Platte River just outside Fremont, Nebraska, and began writing a message “to majority America.” Donald Trump had just become the de facto Republican presidential nominee. As Sasse explained in a Facebook post that would soon go viral, two things had happened that day that he couldn’t shake. His phone had been flooded with voicemails from party leaders asking the first-term Republican to get on board with the GOP’s candidate. And he had gone shopping at Walmart.

Sasse had been critical of Trump throughout the primaries—mocking his insecurity about the size of his hands, crashing a private meeting between Glenn Beck and Fox News’ Sean Hannity to assail the latter’s Trump coverage as “bull,” and even traveling to Iowa to warn voters that Trump talked like a man who was running to be king. Trump, for his part, retorted that the 44-year-old Sasse looked like a “gym rat.” But as Sasse navigated the aisles of Walmart, his shopping trip became a rolling public forum. Shopper after shopper approached him, he wrote, with the same refrain. They were fed up with both parties; they were sick of Trump as well as Hillary Clinton; and mostly, they were tired of Washington punting on its responsibilities.

And so Sasse, putting off his kids’ bedtime bath to keep writing, proposed an alternative. What if there were someone else—a candidate running on a minimalist platform that promised to focus on three or four things, like entitlement reform and fighting terrorism: “I think there is room—an appetite—for such a candidate.”

To the chagrin of the party’s Never Trump rump, Sasse made clear that he himself would not be that candidate. Nevertheless, as his colleagues one by one climbed aboard the Trump train, Sasse steadfastly withheld his support from the GOP nominee. On Saturday, after a tape of Trump boasting of sexual assault was leaked to the Washington Post, Sasse became one of the first Republican senators to call on the GOP nominee to leave the presidential race. Dozens of Republicans, tired of defending their erratic figurehead’s bigotry and reality TV antics, rescinded their endorsements of Trump. But what set Sasse apart from his peers is that he had never wavered in his opposition, even as pressure mounted to fall in line. Most of the few Republican lawmakers who have renounced their candidate are retiring or fighting to hold on to blue-leaning seats—that is, they had nothing to lose or potentially something to gain. Sasse isn’t up for reelection for four years, and his state is as reliably crimson as his ubiquitous Cornhuskers polo shirt.

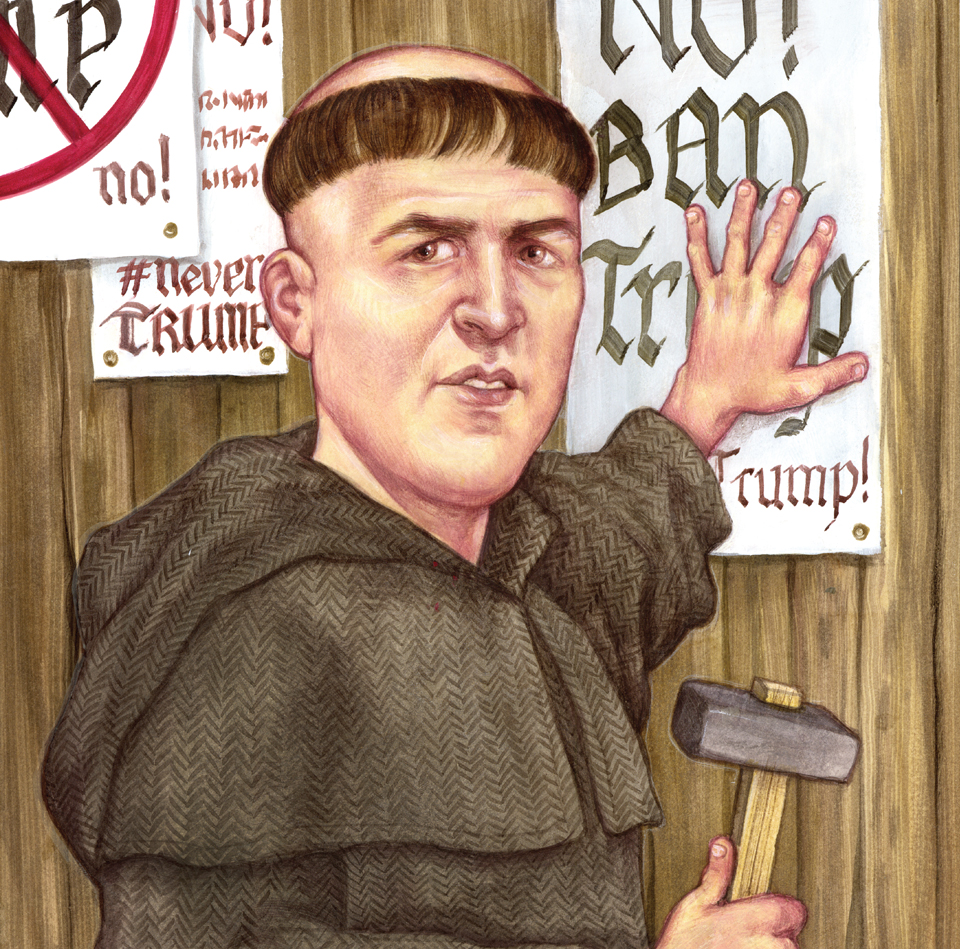

A Trump loss would bring a moment of reckoning for Republicans, one that could put Sasse in a position of unusual influence for a first-term senator—poised, perhaps, to refocus the identity of the GOP in the way that Paul Ryan and Newt Gingrich did before him. As a longtime scholar of the Protestant Reformation and a self-described “crisis turnaround guy,” he has spent his life studying what happens when major organizations become unmoored from their mission. The Republican Party may be his biggest project yet.

But any November soul-searching would require Sasse to wrestle with the factors behind his own political rise in a way that, by training his fire on Trump and limiting his messaging to dramatic manifestos and late-night tweetstorms, he has so far avoided. Sasse may have staked his future in Washington on stopping Trumpism. But Trumpism helps explain how he got there—and it will have to be grappled with before any serious political reformation can take hold. Whether Sasse and his party are prepared to do that may be the defining political question of the coming years.

For a former college president with a Ph.D. in history from Yale, Sasse carries himself with the air of an unusually precocious teen. He parts his dark blond hair into a pair of swooping parentheses and sprinkles even his most sober policy speeches with a slight upspeak. Trump supporters, in their customary kindness, have fixated on his prominent front teeth; someone even contacted his office offering to pay for an orthodontist. Sasse is a little overeager about almost everything, tweeting about doing hundreds of pushups in strange places—the corridor behind Paul Ryan’s office, the floor of his RV. A few years ago, when he was serving as president of his hometown’s Midland University, he severely dislocated his finger after giving a motivational speech to his old high school’s wrestling team. “He clapped his hands and said, ‘I want to drill with somebody!'” said his former coach Ted Husar. Moments later, Sasse caught his hand in his opponent’s shirt and twisted his pinkie into the shape of a Z.

His image reinforces his message—an aggressively relatable politician confronting a Washington power structure that’s way out of touch. In a nod to old Senate tradition, he waited nearly a year after his election to make his maiden speech. But when he took the floor, he was unsparing, warning that unnamed “grandstanders who use this institution as a platform for outside pursuits” were dooming the chamber to irrelevance, ceding governance to the executive branch, and weakening constitutional checks and balances. Sasse often reaches for the high note, arguing that the economic disruption that’s happening now—”disruption” being an essential Sasse buzzword—is magnified because our politicians are so ill-equipped for the challenge. Democrats are selling “central planning in the age of Uber,” he warns; Republicans are “trying to make America 1950 again.”

Sasse grew up in Fremont, a small city of farms and meatpacking plants 45 minutes northwest of Omaha that’s named for John C. Fremont, the first Republican candidate for president following the collapse of the Whig Party. Sasse has described his country childhood there as almost “artificially quaint.” On summer mornings he would wake up at 5 a.m. to catch a school bus to the farms outside of town, where he’d weed rows of soybeans and detassel corn—a Plains rite of adolescence that aids pollination.

The Sasses were a Fremont institution. Ben attended Lutheran services, facing an altar his great-grandfather had helped build. His paternal grandfather, Elmer Sasse, was an officer in the church and a treasurer of the town’s small liberal-arts college, then known as Midland Lutheran. His great-uncle on his mother’s side, Rupert Dunklau, was a manufacturing executive and one of the town’s leading philanthropists. His father, Gary, a Midland alum, coached football and freshman wrestling at Fremont High. People who know them both say a certain focus and competitiveness run in the family.

From the start, Sasse had a knack for playing the angles. At age 10, he pretended to be older to get a job selling Coke at University of Nebraska football games. Three years in a row, he won—and resold—bicycles in a charity swimathon. When the Omaha World-Herald failed to highlight his wrestling team’s upset win over an archrival, he wrote a letter to the editors requesting they treat the sport with a little more respect.

Sasse jokes that he enrolled at Harvard only because he wasn’t good enough to make Nebraska’s wrestling team. But he had always been cerebral and curious for the world beyond his home state. Pamela Murphy, his eighth-grade English teacher, still remembers Sasse’s response when she asked her students to map out their careers. He would go to an Ivy League school, he predicted. And then he would run for president. “I did 35 years with middle school kids,” Murphy says. “With middle school kids, the future is Friday. With Ben, you always knew the future was really the future.”

At Harvard, Sasse “was always working on a scheme,” his roommate Jonathan Ellisor says. Sasse had won a $20,000 scholarship from Coca-Cola but was constantly toying with ventures that never gelled, like scalping Final Four tickets or getting a weekend job as a flight attendant. “It was good pay and he’d be able to fly home whenever,” says Daniel Gallisa, who lived on Sasse’s freshman floor. “We were like, ‘What!?'”

Sasse spent a junior semester at the University of Oxford, living a short walk from the Eagle and Child pub, where his intellectual idol C.S. Lewis once got drunk with J.R.R. Tolkien. Sasse’s flat became a hub for American students’ late-night bull sessions on subjects ranging from the existence of God to the oddities of the British. Sasse was outspoken and articulate but “pretended to be a bit of an anti-intellectual,” his flatmate David Lefer says. “He loved to boast about his farm boy roots—falling in the barn and getting hit by a hay bale or something.” Other times he could be found on the couch, thumbing through a Bible. Some American classmates who were in relationships back home had Oxford flings. “Ben was actually kind of outraged by that,” Lefer recalls. “He was really steadfastly faithful to his girlfriend, and he’d tell us that right after college he was gonna marry her and have three kids—which I think is what he did.” Sasse’s third child, Augustine, named for the Roman theologian, is now five years old.

During his fall at Oxford, Sasse was interviewed by the Harvard Crimson about watching the presidential election from abroad. Sasse’s recent criticism of Trump has a lot in common with what he thought about Bill Clinton in 1992: “It’s quite sad,” he said, “that we tolerate behavior from a national leader that we wouldn’t accept from eighth-grade student council candidates.”

Sasse casts his approach to politics, education, theology, and life in sweeping historical terms. A typical 30-minute speech covers 6,000 years, indulges in a smattering of McKinseyan jabberwocky, and cites C.S. Lewis, Thomas Friedman, and Alexis de Tocqueville. But the basic thrust is that the institutions that have steadied America’s progress over the last 200 years are no longer up to the task. Education, media, politics—they’re all in the throes of what he calls “disintermediation,” as gatekeepers are bypassed in favor of something more direct. Just as nightly news broadcasts have given way to social media, so, too, have the GOP’s power centers been short-circuited by Trump’s direct appeals to voters.

Sasse’s message is rooted in his self-branding as a “history nerd” and “crisis turnaround guy.” After spending his last year at Harvard writing an honors thesis about Martin Luther, Sasse signed on for just over a year at the Boston Consulting Group, where he worked with one of the big three airlines and a European flag carrier as they adjusted to the internet. Sasse likes to talk about the cratering effect that sites like Expedia had on traditional travel agencies, a cautionary tale of the power of disintermediation to usurp established systems: Adapt or die. But he soon left consulting to join a group known as Christians United for Reformation. The organization later merged with the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals, and Sasse would spend nearly eight years helping edit its house magazine.

After college, Sasse had set aside his Lutheranism in favor of a form of Presbyterianism. Both traditions were represented in ACE, alongside Anglicans, Baptists, and Congregationalists. They defined the word “evangelical” by its classical theological meaning: one who believes that salvation comes only through a direct relationship with God. ACE believed that modern Protestantism was a broken institution, as badly in need of a new reformation as the Church had been in the early 16th century. ACE warned against ministers who grow too fond of the center stage and dilute Christianity by pitching it as little more than a self-help program or a get-rich-quick scheme—a spiritual means to secular ends. “They think of themselves as the sort of intellectual elite of evangelicalism,” says Molly Worthen, a history professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Sasse’s and his colleagues’ critiques of their fellow evangelicals then sound a lot like Sasse’s critiques of his fellow Republicans now—a denouncement of false prophets, a call to discuss hard truths, and an embrace of foundational texts. He recently speculated that Trump’s general-election defeat could shake up conservative Protestantism, if younger evangelicals who oppose Trump drift away from the Jerry Falwell Jr. types who back his candidacy.

In 1996, Sasse enrolled at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, lured by its philosophy- and theology-heavy “great books” curriculum, and by a campus that happened to be a short drive from Washington, DC. After writing a master’s thesis on John Calvin, he decamped to Connecticut to pursue a Ph.D. in 20th-century US political history at Yale. From the start, says his academic adviser Glenda Gilmore, Sasse “let his professors know that his goal was to return to Nebraska and get involved in local politics.”

(Read Sasse’s Yale dissertation abstract below.)

At Yale, he regaled his fellow grad students with war stories from outside academia, suggesting that if he was going to make a career in higher education, it would not be as a professor, but as a university administrator. Something from his consulting stint shone through in the way he tackled questions. “He’s ‘Here’s the answer,’ and, no holds barred, ‘Let’s move forward with that answer,'” as one classmate put it. “Whereas a more typical academic was like, ‘Let’s tease this out a little bit more.'”

Sasse’s wife, Melissa, taught at a boarding school outside New Haven, and he didn’t have much time for campus life. On fall weekends he would fly home for Cornhuskers football games. But he still managed to leave an impression: “Even among Yale Ph.D. students, Ben was still a cut above,” says his friend Will Inboden. “He stood out—he’s probably one of the two or three most brilliant people I’ve ever met.” When drinking at New Haven dives, Sasse might sketch out thoughts on a cocktail napkin. “It almost got to be a joke among us,” Inboden said. “Oh, there’s Sasse riffing on the Industrial Revolution again.”

After Yale, Sasse headed off to Washington for a quick succession of jobs in the Bush administration. He took a post helping to run the Justice Department’s in-house think tank, served seven months as “start-up” chief of staff to a newly elected Nebraska congressman, and was later tapped as an assistant secretary at the Department of Health and Human Services, where he worked in the agency’s internal ideas shop. Then, in 2009, while teaching public policy at the University of Texas, Sasse got a call from home. Midland Lutheran College was in trouble.

Midland had struggled financially for years, thanks to diminishing funding from the Lutheran Church and students gravitating away from Fremont. An attempt to revive the budget by building a new event space had drained the endowment. Professors took pay cuts and then salary freezes.

“The president of the board called a meeting of all the faculty and staff. The option was the college would close, or we would go along with the plan of some of the city fathers to hire this guy who actually grew up in Fremont to come in and turn the college around,” says Alcyone Scott, a former Midland English professor who chaired the faculty. (Two foundations close to his great-uncle helped the cash-strapped school afford Sasse’s salary.) “What do you say? ‘Close the door,’ or ‘We’ll go with anything that might give us future life’?” They chose Sasse.

When he took over, Midland was desperately seeking new students, or, as Sasse referred to them, “customers.” Sasse streamlined the core curriculum and instituted a “four-year guarantee” that promised a degree for anyone taking a requisite number of classes each year. He changed the school colors and replaced the tired mascot with a fierce Norse warrior. Hoping to attract secular students, he dropped “Lutheran” from the school’s name. He added a master’s degree in education, so Midland could call itself a university. When a nearby Lutheran school, Dana College, shut down, he offered admission and free housing to its students and leased its buildings, with an eye toward opening a satellite campus. The new students boosted revenue, allowing Midland to quickly scale up. To help lure students to sleepy Fremont, he added 11 new sports. (This spring, Midland even began offering scholarships to online gamers.) After Sasse took over, Midland was the state’s fastest-growing college three years running; by the time he left, the student body had doubled. Sasse had shaped a quiet, struggling Lutheran school into something new and flashy.

To some at Midland, Sasse is a savior. “Not only does he see around corners, but he sees around corners before other people see the building—all the time,” says Tom Adamson, a business professor. But as in the corporate world, where the jobs of longtime employees are often the first thing to go in a restructuring effort, Sasse got rid of tenure, forcing many of the professors who had been there longest into early retirement. He downsized the board by eliminating the seats belonging to the Lutheran Church, and reconstituted it with a smaller group of allies that included his college roommate. (The move happened so quietly that the head of the church’s Nebraska branch found out only after he showed up at a board meeting and was told he was no longer a member.) “You can usurp power, and then you can do certain things because you usurp power, but there might have been a kinder, gentler way to do that than to say, ‘These are the new rules; this is what we’re gonna do,'” Scott says.

There was certainly a cultural disconnect between Sasse and many on Midland’s staff. It was not unusual for faculty to receive emails from the president’s office at 4 a.m., and Sasse could sound more like a consultant than a college president. “He’d say ‘bucket one,’ ‘bucket two,’ ‘bucket three’—I’d never heard that before,” says James Tremain, a former Midland psychology professor who took a 2011 buyout. Many faculty members who did so saw their seats filled with low-paid, part-time adjuncts. Robert Therien, who taught art at Midland for 38 years before departing in 2011, is unsparing: “I think Ben Sasse just pretty much destroyed that school.”

After the school put some $3.5 million into the satellite campus, Sasse’s successors killed the project. The buildings, which had been acquired with much fanfare, now attract vandals—a mar on Sasse’s otherwise largely successful turnaround mission. “In the end, we’re still here,” Adamson says. “And I don’t think anybody else could have achieved that.”

In late 2013, Sasse stepped back from his job to launch a campaign for Nebraska’s open Senate seat. His record at Midland would play an outsize role in his campaign biography. “If he’s an expert on turnaround projects, certainly there’s no bigger turnaround project than the United States of America,” crows Mark Fahleson, a former state GOP chair and longtime friend.

Sasse started off as a complete unknown but used his Washington connections and Fremont loyalties to raise more money than any other candidate—he also got six-figure support from a super-PAC exclusively funded by his great-uncle. Working hard to present a down-home image, he toured the state in a beat-up RV he called the “Benebago,” helping home-school his three kids between stops. In his first commercial, he proposed moving the US Capitol to Nebraska and talked about detasseling corn as country music strummed in the background. At town halls, he told voters he was one of the only people alive who had read the entire Affordable Care Act, and then he wheeled out a nine-foot-tall stack of Obamacare regulations.

Just a few months after he entered the race, National Review, the conservative weekly, anointed Sasse, running a cover showing him standing in a field wearing a blue and orange Midland University windbreaker, bathed in golden light. Sasse won the primary handily, although his political identity remained something of a riddle. Every branch of the party seemed to find something to like, as he locked down the support of tea partiers and the major conservative outside groups while being heralded by the party’s intellectual vanguard and hardliners like Sarah Palin and Ted Cruz. Stuart Rothenberg, a veteran campaign analyst, interviewed Sasse during the race, reporting back that “I am not at all certain who or what Ben Sasse is.”

Sasse’s maiden speech last November laid the groundwork for his estrangement from the GOP. In it, he drew attention to a landmark 1950 address by Maine Sen. Margaret Chase Smith. Though an unflinching opponent of communism, she took to the Senate floor to denounce the “fear, bigotry, ignorance, and intolerance” deployed by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and countenanced by many of her fellow Republicans. “A committed truth-teller challenged someone in her own party, on an issue on which she had ideological alignment with him, to reject straw man arguments and disingenuous attacks,” Sasse said.

At first, Sasse stayed out of the Republican presidential primary, refusing to even discuss the race on Twitter, which he considered a “politics-free zone” for broing out about ’80s rock and making fun of serving kale on Thanksgiving (“doesnt exist in nature #frankenfood”). But in late January, as he was watching an NFL playoff game, a switch flipped. Sasse tweeted a series of questions at the Republican front-runner, saying that Trump had “rightly diagnosed much of what’s wrong in DC,” but that he had questions about how the real estate magnate would govern. Some of those questions concerned Trump’s womanizing and adultery and his history of liberal views on guns and health care. But mostly he was concerned about a candidate who seems to view the presidency as akin to being a chief executive tasked to “run” the country. Sasse once called Trump a “megalomaniac strongman”; that day he piled on, suggesting Trump was a “Nixon-style” figure who believed that America’s ills were nothing an extralegal power grab couldn’t fix.

Trump responded to Sasse’s inquiries with that jab about a “gym rat,” and the relationship went downhill from there. By the end of February, Sasse had published an open letter pledging to support someone other than Trump or Clinton. “Political parties are not families; they are not religions; they are not nations—they are often not even on the level of sports loyalties,” he wrote. “They are just tools. I was not born Republican. I chose this party, for as long as it is useful.”

No one issue or moment triggered the schism. Sasse has knocked the Muslim ban and labeled Trump’s remarks about the Mexican American judge handling his fraud case as “racism.” He vigorously supports the free-trade deals that Trump opposes. But he hasn’t made his fight about any one of those things. Rather it’s a critique of character—Trump’s crassness, ego, and misogyny—that Sasse squeezes into his general What Ails Washington framework. Worst of all, to Sasse, Trump is a big old liar who poisons the well of political discourse—just like those grandstanders in the Senate. “Our public square is plagued by habitual, brazen lying,” he wrote in July. “I do not believe this country can long survive if the public concedes in advance that people in government do not need to be consistently aiming to tell the truth.”

But for all of Sasse’s pleas for seriousness and big ideas, he’s shown that he’s comfortable with elements of Trumpism. In his Senate campaign, he told voters that America was “becoming a socialist mess, like Europe,” and that Obamacare “is arguably the worst law in our history“—he even brought a poster hawking “death panels” to a Fox News interview. He laments Washington’s inability to set aside partisan sniping to get serious on entitlement reform, but he has also called Medicare a “Ponzi scheme” and warned that we’re headed toward “cradle-to-grave dependency.” Sarah Palin, perhaps the second-most-visible icon of the know-nothing conservatism that Sasse now loves to deride, campaigned with him back in 2014, even starring in a TV ad. So did Ted Cruz, the embodiment of the kind of senatorial grandstanding Sasse has subsequently called out. Sasse is making noise about the abrasive, talk radio conservatism that helped America’s most prominent birther become the Republican presidential nominee, but that same wave helped him land his Senate seat. That isn’t particularly surprising. For all its Rotary Clubs and church groups, Fremont isn’t an escape from Trumpian insanity: It’s a birthplace of it.

For decades, one of Dodge County’s biggest employers has been the meatpacking industry. But beginning around the 1980s, when the unions weakened, Fremont experienced a demographic shift, as Latinos came to work in the plants. Some of Fremont’s white residents began to grow uneasy. In 2008, a city councilman introduced an ordinance drafted with the assistance of Kris Kobach, a lawyer who helped popularize self-deportation laws, that would require anyone renting an apartment or home in Fremont to apply for a license at the police station. (Kobach now serves as Kansas’ secretary of state and has advised Trump on immigration policy.) The license would cost $5, but as part of the process you’d have to indicate whether or not you’re a US citizen.

When the mayor cast a tie-breaking vote to defeat the measure in the city council, proponents put it on the ballot, drawing national attention and kicking off one of the most intense political fights in town history. Sasse, in his first spring in charge at Midland, made sure he and the college steered clear as Fremont voters approved the law. A federal court challenge was launched, and undocumented workers were told to avoid Sasse’s favorite Walmart, lest they be picked up by federal agents. Latino residents had their windows shot out. Flyers were posted warning that “providing housing to invaders is treason.”

Opponents of the ordinance argued things had gotten out of hand and, with support from the Fremont Chamber of Commerce, pushed a 2014 repeal vote to take place a few months before the GOP Senate primary. On the campaign trail, Sasse took care to present a hardline on immigration, railing against “amnesty” and suggesting that lawmakers hoping to fix the border crisis should “look to Israel,” which was then building a massive fence on its own southern border.

But he was impossible to pin down on the recall vote. It’s not that the school, one of Fremont’s biggest institutions, wasn’t affected. In late 2013, as the repeal effort neared, a Midland vice president told the Fremont Tribune that the ordinance had hurt fundraising and student recruitment, but he stopped short of recommending a repeal. The morning after Fremont voted to keep the law, Sasse once again avoided giving a straight answer on his hometown’s decision, telling a reporter that Fremont had taken matters into its own hands “because we have a border that’s not secure.”

The ordinance remains on the books, but wary of prolonged court fights, the town has entered into an uneasy detente. Renters must still get a license, but the federal government has avoided verifying applicants’ immigration status. Fremont has yet to evict a single renter.

Still, the law continues to play a major role in Fremont’s political life. This spring, when a new chicken-processing plant was poised to open, one of the ordinance’s loudest supporters helped block the project, warning that the employees would be immigrants, possibly even “of Muslim descent.” Trump boasts that no one was talking about illegal immigration before he entered the race. Of course that’s not true: Some places, including Fremont, were already shouting about it.

Sasse has kept a cautious profile in the press since the primaries ended, telling a New York Times reporter that he turned down 45 consecutive invitations to appear on Sunday shows. His office politely declined requests to be interviewed for this story. But there’s little doubt Sasse’s stand against Trump has boosted his stock and set him up to play a big role in the party. Jennifer Rubin, a conservative Washington Post columnist, has hailed him as the “only Republican to come out ahead in 2016.” While he declined entreaties from her and Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol to jump into this year’s race, Sasse has joined closed-door meetings on the GOP’s future and is already part of the Republicans’ 2020 presidential conversation.

But while Sasse’s anti-Trump agitation may have garnered some plaudits in DC, it’s not going over particularly well in Nebraska, where Trump secured support from roughly two-thirds of Republican caucus-goers. When some 400 delegates gathered in May for the state GOP convention, they considered two relevant resolutions. One—pushed by the nephew of the state’s senior senator and aimed squarely at Sasse—reprimanded officials who dared to back a third-party candidate. The other, pushed by Sasse allies, condemned any candidate who made bigoted or sexist comments.

The first resolution overwhelmingly passed on a voice vote, with fewer than a dozen delegates objecting. The second failed—suggesting that any pending Republican reformation that Sasse might spearhead will have to grapple with the large segment of the party that isn’t disturbed by Trump’s excesses, let alone his policies.

By focusing on his moral case against Trump, Sasse has so far been able to sidestep crafting a political agenda that might offer an alternative to the virulent conservatism and identity politics that shaped Sasse’s own campaign—and that helped launch Trump.

“Look, I appreciate the interest in philosophy and those things, but at its heart we have a political system that is primarily a two-party system,” says David Kramer, a former Nebraska Republican Party chair. “One of the ironies for someone who put as much effort into the Never Trump [movement] is that he never chose to tell us—or the country, for that matter—who he supported. There was ample opportunity for him to get out front and endorse somebody and share why any one of the 17 folks that were running for president would make a good choice for president, and he didn’t do that. I think it’s a little disingenuous when that process is done to say you haven’t made a good choice.”

Sasse’s critics fear he has simply become a Beltway curmudgeon in two years when it usually takes most lawmakers at least a decade. Yes, some Nebraska politicians have had an iconoclastic streak; take Bob Kerrey and Chuck Hagel, two senators who rankled colleagues and burnished their stardom by criticizing their own parties. But their high-profile breaks came after years in office. Apostates have their moments, but no one likes a scold.

A few days before the Republican National Convention, Sasse published an open letter—on Medium, of course—which he said he had begun composing while on a congressional delegation to Afghanistan over the Fourth of July, at a table “backed up against razor wire.” After reiterating that “DC should be disrupted” and using several hundred words to define theological righteousness, Sasse cast his decision not to vote for a presidential candidate in strong moral terms: “If we shrug at public dishonesty—if we normalize candidates who think that grabbing power makes it okay to say whatever they need to in the short-term—then we will be changed by it.”

Around the time he was drafting that letter, Sasse made clear he would not be attending the convention. The senator, his spokesman said, planned to instead take his children on a tour of Nebraska’s dumpster fires.