<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/kurt-b/6927387715/in/photolist-by9F2e-6zFbCh-6zY9Dm-8BNBvQ-6zU7cX-8BKYpx-6zTNdR-6zTLei-6zw4dC-6zXQnE-6zYgpu-6zTCBT-6Cznq2-6zuUdU-6zXEaQ-6zU726-6zY6p7-8BPf2y-9sF3fY-6zED3H-agCN3L-52xDrp-6fpCc7-6eRnAH-8BKtRg-6dfXD4-8NWK8V-6zXX91-8uyX9B-6pkZXP-8vs15X-4wjX3w-Dr4BcN-a6Rmje-D2fZby-4MiBM5-Dr4AE5-8cGP9T-5mjCYL-8vkASi-4wFuGc-7d8CN6-9bXdSy-79r6nF-6fpCgu-wvMMt2-6zFvGs-6zJJhb-6zBJti-8vVP1y">Kurt Bauschardt</a>/Flickr

Car dealers, especially used-car dealers, are notorious for playing unpleasant little games with their customers. So are lenders, especially subprime lenders. (Read “Car Trouble,” our accompanying piece on the rise of the subprime auto industry.) Combine the used-car dealers with subprime lenders and throw in a patchwork regulatory setup—wherein dealers and lenders are regulated by different agencies, making it easy for one to deflect blame onto the other—and you end up with a lot of customers in the lurch. Here are just a few of the tricks—not including the starter kill switch your lender may force you to install—that might come up when you’re shopping for a secondhand car.

Interest rate markups: Used-car dealers often act as middlemen between the buyer and a financier like Credit Acceptance Corp. The financier sets a minimum interest rate based on the customer’s financial circumstances and lets the dealer mark it up and pocket the difference as compensation. (Most dealers shop around in search of the biggest markup.) In effect, this means you are likely paying the dealer a kickback on the lender’s behalf. What’s more, studies have found that dealers impose higher markups on black and Hispanic customers relative to white customers with comparable credit.

Credit kinking: By exaggerating your income and assets, a car salesperson can “kink” your credit to secure a more aggressive deal. The dealer gets paid when the lender buys your finance contract. You, on the other hand, are stuck with a bigger loan than you can afford—one that may soon show up in some Wall Street bond offering.

Offshore add-ons: Credit Acceptance and other subprime lenders now push their own pricey add-ons—products such as extended warranties, vehicle upgrades, gap insurance, and paint and tire protection—and give dealers financial incentives to “pack” loans with them. The paperwork often suggests that these side products, which are purchased disproportionately by low-income customers, are provided by third-party businesses. In fact, those entities are commonly just administrators who quickly transfer the contract to an offshore reinsurance company owned by the lender. After the claim period expires, says John Van Alst, a lawyer for the National Consumer Law Center, most of the money you paid comes right back to your financier—at a favorable tax rate, no less.

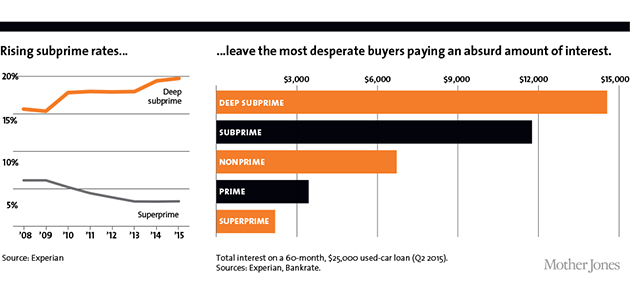

And then there are those interest rates themselves…