Julie Jacobson/AP

A month ago, as Donald Trump celebrated his victories in seven of the 11 Super Tuesday contests, the real estate mogul’s march toward the Republican presidential nomination appeared all but unstoppable. But at the same time, GOP voters in Colorado were quietly setting in motion a process that now threatens to help derail Trump’s candidacy.

While voters in other states registered their support for a presidential candidate, Republicans in Colorado could only vote for county-level delegates. Those county delegates would, in turn, select the delegates who will ultimately choose the party’s nominee at its national convention in Cleveland this summer.

It’s an arcane process that benefits candidates with support among party activists and a well-oiled campaign machine. But the Trump campaign has largely ignored Colorado’s delegate selection process, which culminates this Saturday in the State Republican Convention in Colorado Springs. As a result, Trump could end up with no delegates from the state. That would be a major blow to his effort to secure the 1,237 delegates necessary to win the nomination—and it could offer a preview of even more setbacks as the race turns into a scramble for sympathetic delegates.

Republicans involved in Colorado’s delegate selection process have seen no organized effort on Trump’s behalf. “Trump has, from what I can see, zero campaign infrastructure and organization in the state,” says Ryan Call, a former state party chairman. “I have not so much as seen a Trump banner.”

“He will get, in my estimation, zero delegates in Colorado,” adds Call.

At this point in the race, every delegate is critical. If a candidate reaches 1,237 delegates on the first ballot in Cleveland, that candidate becomes the nominee. But if no one hits 1,237, then delegates will proceed to additional rounds of voting until a candidate hits that magic number. At the start of the convention, most of the delegates will be “bound,” meaning that they will be required to vote for a specific candidate determined by their state’s primary or caucus results. But with each successive round of voting, more delegates will become unbound and will be free to vote for any valid candidate they choose.

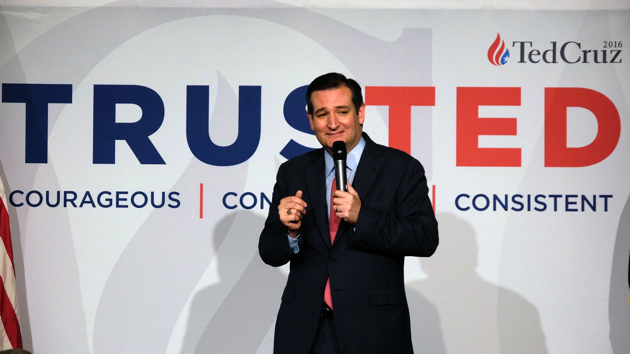

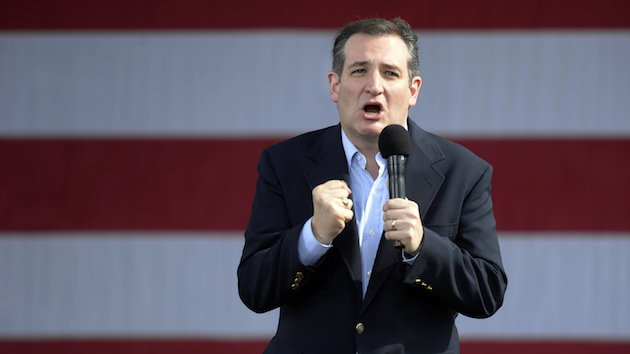

Of course, Trump’s campaign is hoping to win an outright majority on the first ballot in Cleveland. But that prospect has grown less likely as Trump has slipped in recent contests and as Ted Cruz has slowly gained on him, increasing the chances of a contested convention where delegates can select the candidate of their choosing.

If that happens, the process will favor whichever candidate has out-hustled the others at state conventions to ensure that his supporters are selected as delegates. And while Cruz has focused considerable resources on delegate selection, Trump has mainly stayed on the sidelines. He took his first step to compete in the delegate battle late last month when he hired a political operative to oversee his delegate strategy.

The disparity could have the most immediate effect in Colorado. Republican Party rules require that if a state holds a primary or caucuses in which voters select actual presidential candidates, its delegates must be bound on the first ballot. But Colorado is one of three states that opted not to allow voters to choose among the candidates. As a result, Colorado’s delegates will be unbound and free to choose among the candidates on the first ballot. (The other two states with unbound delegates, Wyoming and North Dakota, send fewer delegates to the national convention. Delegates from Guam, American Samoa, and the US Virgin Islands—and a portion of the delegates from Pennsylvania—are not bound by primary results and can also vote freely on the first ballot.)

But there’s another twist: Delegates from Colorado become bound if they write the name of their preferred candidate on their intention-to-run form. So a well-organized campaign with loyalty among party activists could control most of Colorado’s delegates on the first ballot. Trump doesn’t have that kind of organization and popularity among party insiders. But Cruz does.

“There’s been a lot of movement toward Cruz as the last man standing,” said Dick Wadhams, a Republican consultant and another former chairman of the Colorado Republican Party.

On Super Tuesday, which took place on March 1, Republicans in Colorado headed to their local precincts to select delegates to county-level conventions. Those county conventions then sent delegates on to another round of conventions in each of the state’s seven congressional districts. Each district convention chooses three delegates to the national convention—a process that began last week and concludes on Friday. So far, most of the delegates chosen at these conventions have pledged to support Cruz.

On Saturday, the process will culminate in the state convention, where 13 additional national delegates will be elected from a pool of more than 600. Each potential delegate will get 10 seconds at the microphone to make his or her case. In addition, three party leaders will automatically become unbound national delegates, giving the state a total of 37 delegates in Cleveland. (Call is himself vying for a delegate spot on Saturday, but he is not aligned with any presidential campaign.)

Cruz will speak at the state convention on Saturday, while John Kasich and Trump will send surrogates to address the convention. The question is not whether Cruz-pledged delegates will win a majority, but by how much. If Trump’s campaign had invested in delegate-wrangling early on in Colorado, he might not be looking at a potential shutout. Moreover, if Colorado Republicans had held an actual presidential poll at their March 1 caucuses—as most other caucus states did—Trump supporters would likely have turned out to vote for him, and he might have won a significant share of the state’s delegates. “I will always wonder what that did to Trump’s showing in Colorado by not having that poll,” Wadhams says.

Colorado’s process is unusual, but it still offers a preview of the trouble that could lie ahead for Trump. If the convention in Cleveland does move beyond the first ballot, it will look a lot like the Colorado process—with the preferences of the individual delegates determining the outcome. And if the outcome in Colorado is any indication, that doesn’t bode well for Trump.