Nicolás MaduroAriana Cubillos/AP

A quick Google search suggests that times are tough in the land of Bolívar:

- “Venezuelan President’s Relatives Indicted in US for Cocaine Smuggling”

- “Venezuelan Opposition Politician Shot to Death at Rally, Party Says”

- “Venezuela Has Bigger Oil Reserves Than Saudi Arabia—Yet No Toilet Paper in Stores”

- “Venezuela’s Poverty Soars”

On Sunday, Venezuelans will head to the polls for legislative elections that could upend the country’s political calculus for the first time since socialist firebrand Hugo Chávez swept to power 17 years ago. Here’s what you need to know heading into the weekend:

Chavismo might actually lose. For years, Chávez’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV in Spanish) has dominated all branches of government, constantly fighting off a fractious opposition that recently has united under the broad-spectrum banner of the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD in Spanish). And even when Chávez died in March 2013, his successor, Nicolás Maduro, was able to edge out MUD candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski with 50.6 percent of the vote. Currently, the PSUV holds 96 of 165 National Assembly seats, 20 of 23 governorships, and 242 of 337 mayoral spots.

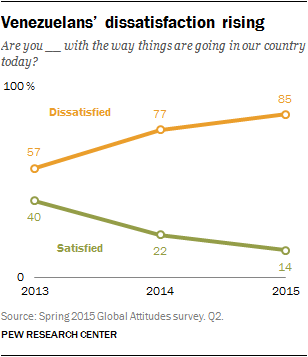

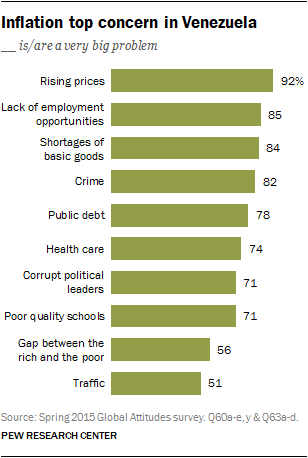

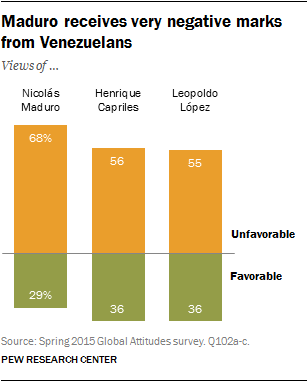

At a Monday rally in Caracas, Maduro summed up his party’s take on the opposition: “What is the plan of the rotten right-wing? End the social missions, end the pensions and send old people to work…Privatize education…Bring the International Monetary Fund here and give them our oil wealth.” Still, even with a big jump in the past month, Maduro’s popularity is hovering around 30 percent. Last year’s violent protests—some 43 died over several months, and a Human Rights Watch report says it found “strong evidence of human rights violations committed by Venezuelan security forces”—have given way to a year of campaigning, but the problems that led to nationwide demonstrations have in some cases worsened: chronic food shortages and endless lines at the grocery store, a nonsensical currency policy, a spiraling GDP, rampant violence, weak oil production, and continued media repression. (Exacerbating all of this: Oil prices have dropped to $40 a barrel, down from $100 a barrel when the protests started.)

And so the opposition’s campaign strategy has been…not to campaign. Not a whole lot, anyway. David Smilde, a sociologist at Tulane University and a senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America, says the opposition campaign has been a minimalist agreement on candidates and basic, abstract messages—and that’s about it. “The government is doing a great job of making them popular,” he says.

Watch out for the ni-nis. Venezuela is notoriously divided between chavistas and the opposition. Smilde points out that roughly 30 percent of Venezuelans identify as chavistas and another 30 percent as opposition, but that 40 percent are known as ni-nis—ni chavista ni oposición, neither chavista nor opposition. Many observers see December 6 as the moment the ni-nis will finally break for the opposition. It could also be an opportunity for those chavistas fed up with Maduro—according to New York University’s Alejandro Velasco, some chavistas see Maduro as weak, not truly revolutionary, and complicit in corruption—to send a signal that they expect a change, and soon.

The shooting death of an opposition politician won’t be solved anytime soon. On November 25, a local Democratic Action party official named Luis Manuel Díaz was shot and killed at a rally in the town of Altagracia de Orituco, in the central plains state of Guárico. Another opposition leader blamed “armed PSUV gangs” for Díaz’s death. The US State Department condemned the attack, and in a statement, an Amnesty International official said that “the killing of Luis Manuel Díaz provides a terrifying view of the state of human rights in Venezuela.”

On Monday, three men were arrested in connection with the shooting. Reuters reported the government has claimed that Díaz was involved in a union-linked gang dispute, and his death was being used to score political points.

Hillary and Jeb have weighed in. Neither had nice things to say. On Monday, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton said that Maduro’s government “has been doing all it can to rig these elections” and that she was outraged at Díaz’s “cold-blooded assassination.” On Wednesday, Jeb Bush took a shot at Clinton, saying in a statement, “Instead of standing up for democracy, free elections, and the rule of law in Venezuela, President Obama and Secretary Clinton have acquiesced to dictators like Chávez and Maduro whose regime of criminality, corruption, and narcotrafficking threatens Venezuela, the Western Hemisphere, and our own interests.”

Opposition leader Leopoldo López is still in prison. López, the handsome, media-savvy, Harvard-educated former mayor of Chacao, an upscale Caracas municipality, made international headlines when he was jailed following a February 2014 protest that turned violent. A New York Times editorial called his subsequent trial “a travesty”; he was sentenced to nearly 14 years in jail in September on what NYU’s Velasco calls “trumped” charges.

He’s among the opposition’s harshest critics of Maduro and chavismo, and a divisive figure; a US Embassy cable from 2009 includes the header “The Lopez ‘Problem,'” with the following description: “He is often described as arrogant, vindictive, and power-hungry—but party officials also concede his enduring popularity, charisma, and talent as an organizer.” (This Foreign Policy profile from July attempts to reconcile López’s past with his present image.)

But the 44-year-old López’s future, Velasco says, is tied to the election: Should the opposition win a majority in the National Assembly, leaders have said they will pass a law to grant amnesty to López and other political prisoners.

There are three possible outcomes to the election. According to Velasco, they are:

- The opposition wins a simple majority in the National Assembly. Velasco says it would privilege the opposition’s more moderate voices and enable the passage of necessary reforms, such as raising gas prices, eliminating some subsidies, and devaluing the bolívar to bring it closer to its black-market value.

- The opposition wins a supermajority. Hardline voices like López and María Corina Machado would have more sway, and the opposition could call for Maduro to face a recall referendum.

- Chavismo hangs on and continues to be the majority party: “the most harmful” situation, both politically and on the ground, according to Velasco.

“What’s interesting in the case of Venezuela over the last 10 years,” Velasco says, “is whenever there is the significant likelihood of stepping over a precipice—huge amounts of political violence, the complete collapse of the oil industry, whatever the most cataclysmic scenario is—Venezuelans have always found a way to step back from it.”