<a href=http://www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/SIPA-Balkis-Press-Sipa-USA-I-unknown-524106-0-/436e66e3d23c4a9897948c7df1686b15/8/0>Balkis Press</a>/AP

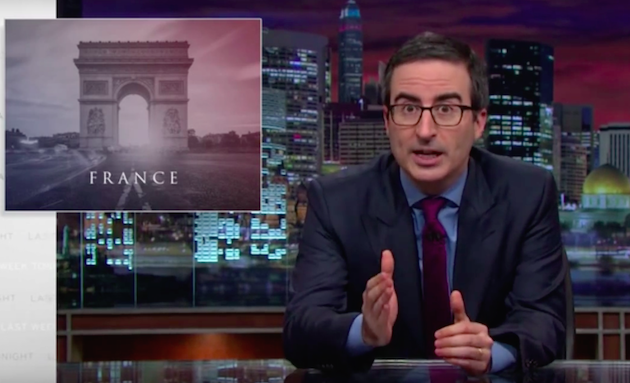

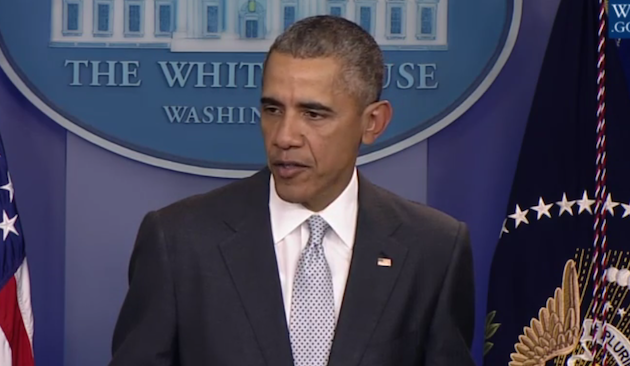

At a Monday press conference at the G20 meeting in Turkey, President Barack Obama was repeatedly asked by American reporters a version of this question: What are you doing to defeat ISIS? CNN’s Jim Acosta put it in these Twitterish terms: “Why can’t we take out these bastards?” His passionate formulation seemed to imply that the Obama administration was not doing everything reasonably possible to vanquish ISIS. And throughout the presser, Obama explained that there was a strategy in place, asserted that other ideas (such as sending in ground troops or establishing a no-fly zone in Syria) were constantly being scrutinized, and expressed frustration that he was being asked the same question (what’s your plan?) repeatedly.

Obama was right. He does have a strategy, and for more than a year the United States has taken many actions to thwart ISIS. Whether these steps are the best that can be attempted (weighing all the complicated costs and benefits) is subject to debate. But Obama’s opponents—particularly those Republicans seeking to succeed him in the White House—often assail him as if he’s a feckless, do-nothing commander-in-chief who has no understanding of ISIS and has mounted practically no effort to counter these murderous extremists. But that’s hardly the case.

Ask the White House what the president has done to combat ISIS—the president prefers to call the group ISIL—and aides will quickly point out that Obama has forged a coalition of 65 nations that are supporting local forces in Iraq fighting against ISIS. This effort has launched 8,100 airstrikes on ISIS targets in a little more than a year. (For comparison’s sake, there have been about 400 drone strikes against targets in Pakistan since 2004.) The White House notes that US military forces recently struck 116 ISIS fuel trucks and disrupted the group’s oil-smuggling and financing capabilities. And two weeks ago the president announced he would be sending additional special operations forces to work with Kurds battling ISIS in northern Syria. At the same time, Obama noted the administration would step up supplying equipment to anti-ISIS forces in Syria.

For weeks, administration reps have been describing their anti-ISIS efforts. In late October, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter testified on Capitol Hill and claimed that the US military effort to help moderate Syrians fighting to gain control of Raqqa, an ISIS stronghold in Syria, had made gains and that these Syrians were 30 miles from the strategically important city. He noted the overall air campaign against ISIS was intensifying, and he said the United States was prepared to provide more air support and equipment to Iraqi forces battling ISIS, provided that the Iraqis demonstrate progress and the ability to preserve recent gains in Anbar province. “We’ve given the Iraqi government two battalions’ worth of equipment for mobilizing Sunni tribal forces,” Carter said. “As we continue to provide this support, the Iraqi government must ensure it is distributed effectively.”

Carter cited recent successes on the ground: the Kurdish-led hostage rescue mission in northern Iraq and assorted raids against ISIS leaders: “The raid on Abu Sayyaf’s home, and strikes against Junaid Hussain and most recently Sanafi al-Nasr, should all serve notice to ISIL and other terrorist leaders that once we locate them, no target is beyond our reach.” He told the senators that all the ideas touted by Obama’s critics—a no-fly zone, a buffer zone, humanitarian zone—had been reviewed and pose their own challenges.

In a November 12 speech, Secretary of State John Kerry also outlined details of the administration’s anti-ISIS campaign. He said that the number of airstrikes was rising: “There were more than 40 just last night.” He added that “the coalition and its allies on the ground have defended Mosul Dam and other vital facilities in Iraq while also preventing a terrorist assault on Baghdad. We have driven [ISIS] from the critical border town of Kobani…We’ve seen the city of Tikrit liberated.” He pointed out that “thousands of American advisers” were training and assisting Iraqi security forces. “We have significantly degraded [ISIS’s] top leadership, including Haji Mutazz, the organization’s second in command,” Kerry added, “and we continue to eliminate commanders and other personnel from the battlefield.”

And there’s more: helping Iraqi forces aiming to take back Ramadi and boosting the shipment of supplies and ammo to Syrians fighting ISIS. Also, Kerry remarked, the Obama administration was trying to bolster the efforts of its European allies and those allies in the region: “Not long ago, [ISIS] controlled more than half of Syria’s 500-mile-long border with Turkey. Today, it has a grip on only about 15 percent, and we have a plan with our partners to pry open and secure the rest.” And, Kerry noted, the administration had been pushing a diplomatic initiative in Syria aimed at deescalating the conflict within that country, which, if successful, would allow for a more concentrated multilateral assault on ISIS.

“Remember, this [anti-ISIS] coalition has only been together for 14 months,” Kerry said. And administration officials like to toss out this particular stat: ISIS has lost between 20 and 25 percent of the populated territory it used to control in Iraq.

So Obama and his team can recite a long list of actions and a short—but significant—list of accomplishments. Still, the Paris attacks (as well as attacks in Beirut and the downing of a Russian airliner, which have been attributed to ISIS) and the ability of ISIS to maintain its quasi-state within not one but two countries can be cited as a sign that ISIS, to some extent, is prevailing, even if it has lost ground.

Obama’s anti-ISIS plan is nuanced, multifaceted, tethered to the vexing realities of the region, and focused on long-term success—and it avoids the risks and unforeseen consequences of deploying American ground troops to directly engage with ISIS on Syrian or Iraqi territory. It does not involve grand or sweeping actions. It does not promise complete and immediate success by a date certain. Consequently, Obama is vulnerable to criticism from those who claim bolder (if sometimes unspecified) action would yield better and quicker results. Perhaps additional steps could produce more progress. For example, Brian Katulis, an expert on the Middle East and terrorism at the Center for American Progress, faults Obama for not leaning hard enough on partners in the region, such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey, to make busting ISIS a top priority. But with the national discourse so thoroughly shaped by politics and ideology, it will be hard to have a cool and reasonable debate over alternatives or add-ons to Obama’s approach.

The Bush-Cheney invasion of Iraq in 2003 unleashed forces and challenges that might require decades to counter, and Obama has been trying to implement a series of actions to end the danger that war generated. Yet any decent plan could take a long time to take out the bastards.