iStock

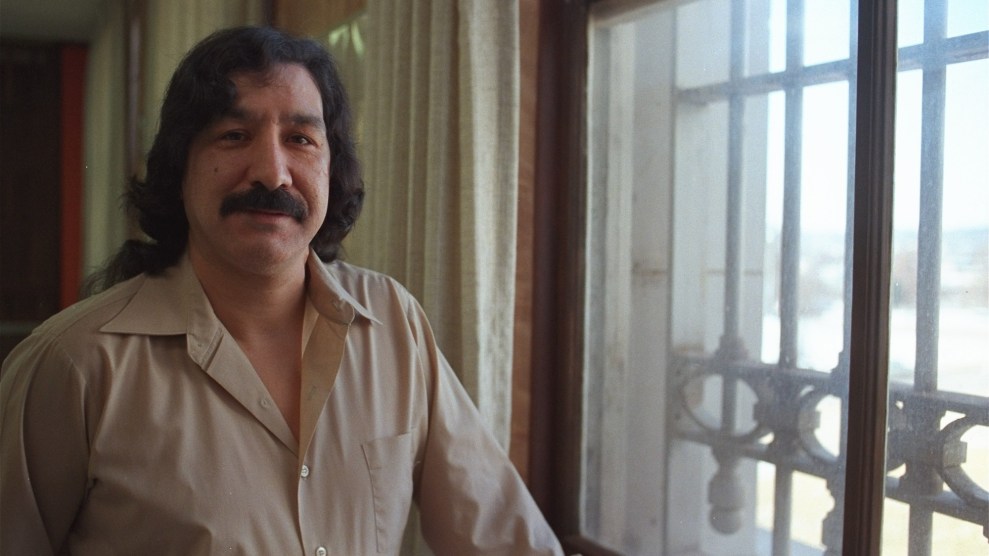

When Richard Bernstein decided to run for a seat on the Michigan Supreme Court, he had a lot stacked against him: He was a Democrat, he had no experience as a judge, and he was blind—something he’d dealt with his entire life.

Bernstein spent more than $1.8 million of his own money to get that seat, making history by becoming the first blind justice in the state’s history.

That ranks as the third-highest amount of overall spending in judicial elections during the 2013-14 cycle, according to the latest installment of “The New Politics of Judicial Elections,” a series of reports that have tracked spending trends in judicial elections since 2000. Even though he put $1.8 million of his own money into the race, Bernstein says it was just enough to get the job done, especially with a tide of PAC money flowing through various entitles that funded ads against him.

“You’re not really able to see firsthand the amount of money that was spent against [you],” Bernstein told Mother Jones this week. “We were able to raise the $2 million, but that is what allows you to be competitive. I was able to raise and spend the bare minimum to contend in a race like this.”

Bernstein says he’s very much in favor of voters choosing which judges sit on the bench. “It’s not just about raising money,” he says. “What it’s really about is having to go out and connect with people.”

But he can see why people are concerned about dark money flooding the zone. That’s one of the main takeaways of the latest “New Politics of Judicial Elections.” A product of Justice At Stake, a group focused on limiting special-interest interference in courts, and the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute, the reports have documented the explosion in judicial spending over the last 14 years. Supreme Court justices in 38 states must face voters to either earn their seats or keep them. But over the last few years, what were once sleepy, local affairs have grown into multimillion-dollar races that have increasingly drawn the attention of special-interest groups from all over the country.

According to the newest report, released this morning, state Supreme Court candidates spent more than $34 million on races in the 2013-14 election cycle. That total was slightly less than the amount spent in 2011 and 2012. One reason is that there were a large number of unopposed candidates. Even so, political parties and outside special interests poured $13.8 million into the races. That figure is 40 percent of the total amount of money spent during that cycle, $13.8 million. It’s the first time such a huge percentage of spending came from these outside groups during a non-presidential election cycle.

“The big takeaway, I would say, is that it’s well financed interests who are doing this,” said Scott Greytak, Justice At Stake policy counsel and research analyst, and the lead author of the new report. “And they have clear, known, financial interests before the courts.”

In the 1990s state Supreme Court candidates raised a combined $83 million. However, that changed after the political right, mainly through Karl Rove, saw a way to reshape what were seen as anti-business state courts by playing more aggressive politics in state judicial races (see previous Mother Jones coverage of that dynamic here). Since then, state Supreme Court candidates have raised more than $236 million, but independent spending by special-interest groups and state political parties has brought the total to nearly $325 million since 2000. “How do we convince Americans that justice isn’t for sale—when in 39 states, it is?” former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Sue Bell Cobb wrote in Politico in March. “When a judge asks a lawyer who appears in his or her court for a campaign check, it’s about as close as you can get to legalized extortion.”

Donors typically want the reassurance that the judges they write checks for will think the way they do and will “rule accordingly,” Cobb notes. According to a basic tenet of a typical judicial code of conduct, the appearance of bias undermines the judicial system. When judges are forced to run inherently political campaigns, the line blurs, the theory goes.

“Unfortunately, politicized judicial elections don’t seem to be going away,” says Alicia Bannon, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program, and a coauthor of the report. “We’ve been tracking spending in state Supreme Court races since the year 2000 and we’ve continued to see a trend of highly politicized races and a flood of money coming into state Supreme Court contests.”

Some other notable numbers:

- Direct contributions to judicial candidates of more than $1,000 made up a majority of the contributions in 15 of the 19 states with judicial elections in the 2013-14 cycle.

- In three states (Alabama, Pennsylvania, and Illinois), contributions of $1,000 or more made up at least 95 percent of all contributions. Small donors, by and large, don’t have a seat at the table.

- The top 10 spenders nationwide—including the Republican State Leadership Committee, Justice for All NC (a Republican effort), the Michigan Republican Party, Campaign for 2016 (a trial-lawyer-backed organization in Illinois), and others—accounted for 40 percent of all contributions during the 2013-14 cycle, including candidate contributions and outside, independent spending. Two-thirds of all outside spending by those top 10 spenders supported Republican and conservative candidates, as 7 of those top 10 spenders were conservative or business groups or state Republican parties. That reflects a pattern that’s been in place over the last several cycles.

- The third-biggest spender of the cycle was Bernstein, the Democratic state Supreme Court justice in Michigan, who donated more than $1.8 million of his own money to his successful campaign.

- Three states saw record spending in the 2013-14 cycle: North Carolina ($6 million), Montana ($1.5 million), and Tennessee ($2.5 million).

- Retention elections, which are races where voters give a yes or no vote to keeping a judge on the bench, continued to be costly affairs. Four states held retention elections and saw a combined $6.5 million in total. Between 2001 and 2008, retention elections averaged a total of $490,000 total per cycle.

The sums of money involved in these races have forced judges to run campaigns, which cost money. And while some judges are okay with that, others feel that it degrades the position. HBO’s John Oliver mocked judicial elections in a segment earlier this year:

The money often comes from lawyers who appear before judges and from lobbyists acting on behalf of businesses and special interests that also have business before the court.

“There’s been a real shift in norms…among judges and judicial candidates in terms of what they’re willing to do and say in their campaigns,” Bannon says. “And I think it has troubling implications for the public’s confidence in the fairness of our courts. In the end, I don’t think the public wants our judges to be politicians in robes, but increasingly that’s what we’re seeing as these campaigns continue to be dominated by special-interest money and are bearing all the hallmarks of an ordinary political contest.”

Consider Judith French, a sitting Ohio state Supreme Court justice appointed in 2013 by GOP presidential candidate and Ohio Gov. John Kasich. French is listed in the report as having raised the second–highest amount of contributions during the 2013-14 cycle ($1.1 million). During a political rally before the November 2014 election, French told a Republican gathering:

I am a Republican and you should vote for me…Let me tell you something: The Ohio Supreme Court is the backstop for all those other votes you are going to cast. Whatever the governor does, whatever your state representative, your state senator does, whatever they do, we are the ones that will decide whether it is constitutional; we decide whether it’s lawful. We decide what it means, and we decide how to implement it in a given case. So forget all those other votes if you don’t keep the Ohio Supreme Court conservative.

French couldn’t be reached for comment, but she told local media that she was talking about small-c conservative philosophy, meaning that she would uphold the rule of law and not legislate from the bench. Nonetheless, the Ohio Democratic Party accused her of being overly partisan, and Ohio’s largest state-employee union asked her to recuse herself from a case earlier this year. (She didn’t.)

Money doesn’t always buy victory. Clifford Taylor, the former chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court, was himself an avid fundraiser during three campaigns: He raised $1.3 million for his election in 2000 and $1.8 million during the 2008 campaign. But that didn’t prevent him from becoming the first sitting chief justice in the state’s history to suffer defeat at the hands of a challenger in 2008. Taylor, a Republican, was attacked by the state’s Democratic Party in more than 2,800 ads, which painted him as a tool of business interests. And although he had more overall supportive airtime than his challenger, his bad relationship with trial lawyers, along with an ad that alleged he fell asleep on the bench—a claim he disputes and that Factcheck.org said wasn’t proven—may have helped generate votes that cost him the race.

“People aren’t buying judges,” he said. “People are buying an approach to the law. And that’s a very different thing.”

The fight against money in judicial elections by groups like Justice At Stake, he said, is a political ploy to advance liberal policy that otherwise didn’t get through state legislatures.

“They consider the judicial branch to be the action arm of the American left,” he said.

The money spent, such as the $1.6 million spent by the Republican State Leadership Committee across three states and the $2 million spent in Illinois by the trial-lawyer-backed Campaign for Illinois, disproportionately goes to fund television ads. Some of the ads are fairly positive, but the report notes that many of them distort opponents’ records—such as the one portraying Taylor as sleeping on the bench—or, more typically, paint opponents as soft on crime.

During the 2013-14 cycle, more than half the television ads focused on criminal justice themes. The report points to studies that have linked the number of television ads that run during a state Supreme Court election to the decreased likelihood that a judge is to rule in favor of a criminal defendant. The report cites a 2013 US Supreme Court death penalty case in which Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a dissent discussing judges’ ability to override jury decisions in death penalty cases. Citing data that pointed to Alabama having a higher number of cases where judges overrule juries who vote against the death penalty, Sotomayor said electoral pressures were likely to blame:

“The only answer that is supported by empirical evidence is one that, in my view, casts a cloud of illegitimacy over the criminal justice system: Alabama judges, who are elected in partisan proceedings, appear to have succumbed to electoral pressures.”

She also cited ads in Alabama where judges seem to boast about the number of people they have sentenced to death.

Another major issue highlighted by the report is the continued rise in spending in retention elections—it has increased twelvefold, according to the report. In 20 states, judges run in retention elections to earn additional terms on the state Supreme Court bench. As the report points out, these races, historically, were low-budget affairs. But after 2010, when three Iowa Supreme Court justices faced a brutal retention election, and lost, retention elections have been seen as a way to flip courts. During the last cycle, spending on retention elections in four states (Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Wyoming) came in at nearly $6.5 million.

“Any form of judicial selection is going to have some form of politics in it,” Bannon says. “I think the concern is when, in the context of judicial elections, what we’ve been seeing is that the role of money has become so all-encompassing and is really privileging a certain set of interests in ways that I think raise legitimate questions about whether or not that might be impacting the decisions courts are making.”