<a href="http://www.istockphoto.com/photo/handgun-57711994?st=86d511f"> arda sava?c?o?ullar?</a>/iStock

According to a new report from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, racial bias can affect the likelihood of people pulling the trigger of a gun—even if shooters don’t realize they were biased to begin with. Researchers found that, in studies conducted over the past decade, participants were more likely to shoot targets depicting black people than those depicting white people.

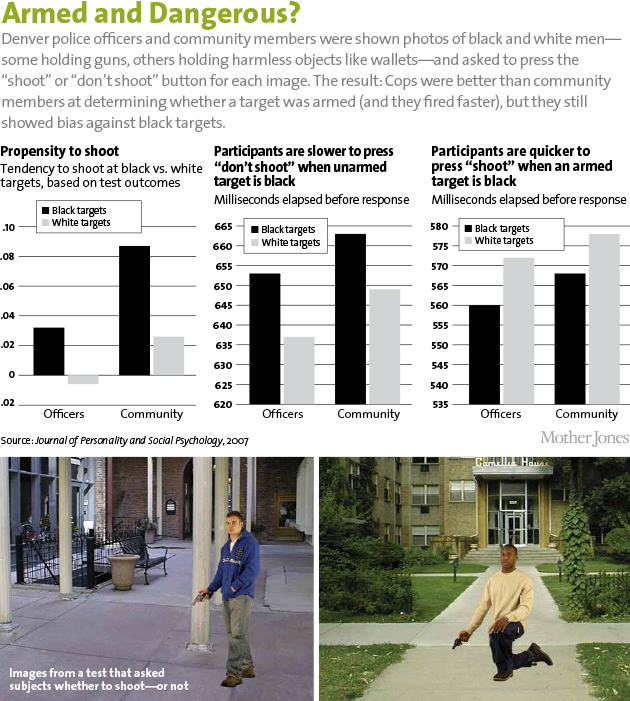

A team led by researcher Yara Mekawi looked at 42 studies that used first-person-shooter tasks to identify shooter bias. In the lab, images of black or white people were shown to participants, who then had less than a second to decide whether they would shoot the target. In some images the people were armed, and in others they were holding another object, like a cellphone.

The meta-analysis showed that the participants were quicker to shoot when an armed person was black, slower to choose not to shoot when an unarmed person was black, and more trigger-happy toward black targets in general.

There was little difference between false-alarm shootings between black and white targets overall; however, in states where gun laws are less strict, shooter bias against black targets increased—unarmed black targets were more likely to be shot. The bias only got worse in areas that were more racially diverse.

“What this highlights,” Mekawi told NPR, “is that even though a person might say, ‘I’m not racist’ or ‘I’m not prejudiced,’ it doesn’t necessarily mean that race doesn’t influence their split-second decisions.”

Racism, it turns out, can actually be hardwired into our brains. Last year on the Inquiring Minds podcast, neuroscientist David Amodio explained why we discriminate even if we don’t want to:

When we look at faces of individuals of a different race, a part of our brain called the amygdala often gets active. The amygdala is involved in learning and, specifically, in a type of learning called fear conditioning…The problem is that because our culture is filled with racial stereotypes, many of us “learn” inaccurate and prejudicial information about those who look different. And the amygdala operates extremely rapidly, long before our conscious thoughts have time to react. Thus, the operations of this and related brain regions, “if left unchecked, they might lead to the expression of some bias in a way that you don’t intend,” says Amodio.

The good news is, as Chris Mooney pointed out in his January/February 2015 Mother Jones cover story on the science of racism, research is providing insights into how these biases can be overcome. That’s why the authors of the meta-analysis are saying their results could be especially important in law enforcement training—to help police address racial bias before it becomes deadly.

“Understanding the factors that contribute to shooter biases in the laboratory,” they write, “may provide critical insight into targets of change for interventions designed for gun-owners and law enforcement officers.” But there’s still more work to be done: “Research identifying effective interventions is needed to maintain the basic human rights of racial and ethnic minorities, keep communities safe, and increase the effectiveness of policing.”

This story has been revised.