Officers involved in the 2014 shooting of a homeless man in Albuquerque were told to wait two days before speaking with investigators.A screenshot from footage released by the Albuquerque police.

Last Friday, in a courthouse in New Mexico, special prosecutor Randi McGinn asked police psychologist William Lewinski whether he advised investigators to wait several days before interviewing an officer involved in a shooting. McGinn was asking because two Albuquerque police officers shot and killed a homeless man on March 16, 2014, in the foothills of the Sandia Mountains, and they had been told to wait two days before giving a statement. The lag in time seemed odd to McGinn, who is pursuing murder charges against the officers.

Lewinski, founder of the research group Force Science Institute, is a controversial figure among prosecutors like McGinn. Recently, he came under fire for publishing studies that critics said were not subject to peer review, and for using those studies in his work as an expert witness when testifying on behalf of officers involved in shootings. Lewinski responded to McGinn’s question by saying, “That’s what the professionals and the experts in law also state.” He added that “if you can eliminate bias, memory aids such as walking through a scene, looking at video—the things that are currently used in the police practice—do enhance memory.”

The same day McGinn was interviewing Lewinski in court, cops working one state away, in Arlington, Texas, were dealing with fallout from a police trainee’s fatal shooting of 19-year-old Christian Taylor. Arlington’s police chief explained to reporters that the two officers involved had not yet been interviewed due to a standard department procedure, and that he expected the officers to submit their statements in 7 to 10 days. (Investigators interviewed one of the officers on Monday.)

Albuquerque and Arlington are not outliers. For years, departments in states like Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Oregon, Texas, and Wisconsin have required a waiting period of at least two days. In Dallas, 72 hours must pass. In Baltimore, where six police officers have been charged for their involvement in the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray, a union contract compels cops to wait 10 days before speaking with investigators.

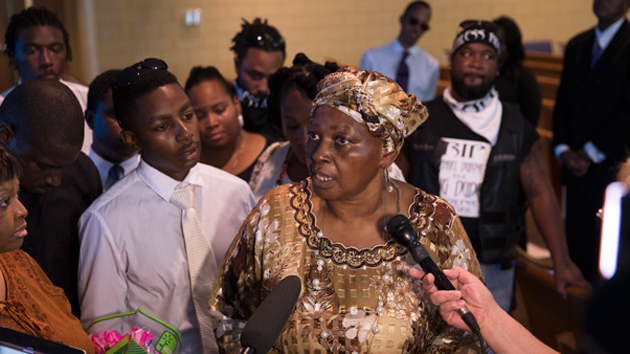

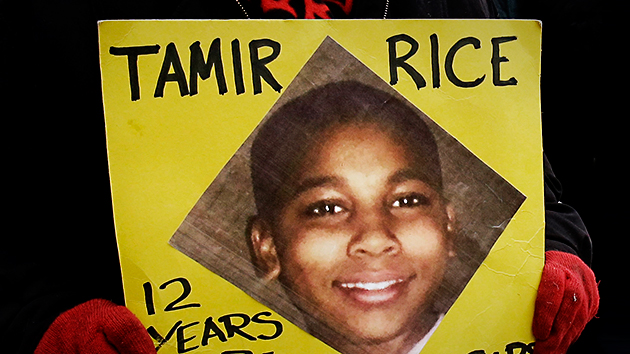

In the aftermath of controversial police shootings, from Michael Brown to Tamir Rice and Samuel Dubose, the public has repeatedly seen that an officer’s account—”I almost got run over by the car” or “I felt like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan“—can have big implications for a case, swaying internal investigators, prosecutors, and grand juries as they determine whether a police shooting was legal or justified. It is unsurprising, then, that over the past year the question of how long officers should wait before giving their accounts has been fiercely debated. Policing experts have raised a number of issues, including, most importantly, the validity of the science—promoted often by Lewinski—behind delaying interviews.

Local officials and union attorneys who embrace the so-called 48-hour rule say stress can interfere with an officer’s ability to recall details. “The science behind how people remember things, particularly those that are involved in a high-stress, adrenaline-infused situation, has shown that memories can often be inaccurate if they are immediate,” Sean Smoot, a police union attorney who represents officers in Illinois, testified to the US Commission on Civil Rights in April.

When the civil rights commission pressed Smoot for data supporting his claim, he cited the work of Lewinski and the Force Science Institute. In an April 2014 Force Science newsletter, Lewinski wrote, “The overall benefit of waiting while he or she rests and emotionally decompresses far outweighs any potential loss of memory.” What’s more, he said, “Delay enhances an officer’s ability to more accurately and completely respond to questions.”

But the science shaping rules about when officers should be interviewed, several policing experts warn, is inconclusive at best, and shaky ground on which to base investigations with potentially criminal outcomes. In fact, a 2010 experiment conducted by University of South Carolina professor Geoffrey Alpert found that an officer’s recollection of threats at the scene actually weakened slightly over time. The scientific conclusions about when officers should be interviewed after a shooting, Alpert says, “remain blurred.”

In response to Smoot’s testimony, Samuel Walker, a criminologist at the University of Nebraska in Omaha, reviewed a meta-study of psychological research on the relationship between stress and memory. The 2008 study concluded that “there is little evidence to support the view that emotional stress is bad for memory,” Walker wrote. “Police unions and their advocates have made false and self-serving claims about the scientific evidence on the impact of trauma on memory.”

When I asked Lewinski about the findings, he referred me to the recommendations of the International Association of Chiefs of Police’s psychological services section. “That prestigious and knowledgeable group disagrees strongly with Dr. Walker,” Lewinski said in an email. (The association’s guidelines on officer-involved shootings don’t quite line up with Lewinski’s 48-hour recommendation; they state that “officers should have some recovery time before providing a full formal statement,” ranging from a few hours to several days, and that “an officer’s memory will often benefit from at least one sleep cycle prior to being interviewed leading to more coherent and accurate statements.”)

The science isn’t the only concern that policing experts have raised in recent months: In her line of questioning last week, McGinn suggested the delay could give officers an opportunity to review video or “consult with their peers who were involved before they ever give a statement.” Walter Katz, a Los Angeles-based attorney focusing on police accountability, told me that “there’s always the concern about either contamination or having statements which are essentially fabricated.” And McGinn and others have asked if the delays amount to special treatment a regular citizen wouldn’t be afforded. (Union officials have pointed out that due process for ordinary civilians does not provide enough protection for law enforcement officers.) In the fragile atmosphere that tends to follow police shootings, such suspicions could well corrode public trust.

What’s more, rules delaying interviews also overlook the fact that officers may prefer to get their interviews out of the way, says David Klinger, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “In the absence of sound scientific evidence, why make them wait?”