<a href="http://www.istockphoto.com/photo/prisoner-7438019?st=0fd6e45">MmeEmil</a>/iStock

After being charged with burglary in 2013, Peter Yepez waited in the Fresno County, California, jail for a month before his assigned public defender came to talk to him. This delay was a sign of what was to come: Between arraignment and sentencing Yepez spent more than a year being shuffled between nine different Fresno County public defenders, who he says told him they did not have time to work his case

By then he’d missed his daughter’s graduation and his young son’s memorial service, and had fallen into depression.

Though he was originally accused of a domestic burglary, during those many months prosecutors added additional charges to his case, alleging that a victim had been present during burglary even though a police report filed at the time of the crime had claimed no one was there. The new allegations would bump his original charge to a violent felony. Still, Yepez’s public defender advised to him to accept all the charges and the punishment that would come—and so he did. Now Yepez’s record reflects a felony conviction.

Today Yepez is a plaintiff in a lawsuit filed recently by the American Civil Liberties Union. The lawsuit, intended to expose the deficiencies in Fresno County’s public defense system was filed against Fresno (a county in which close to a quarter of the population lives below the federal poverty line), the state of California, and its governor, Jerry Brown, for systematic issues that the ACLU claims led to thousands of poor defendants to be denied their constitutional right to adequate representation. All of this, the ACLU says, has perpetuated greater racial inequalities in the criminal-justice system.

According to the ACLU’s complaint:

- With an annual caseload of 42,000 and fewer than 100 people on staff, the Fresno County Public Defender’s Office is unable to keep up.

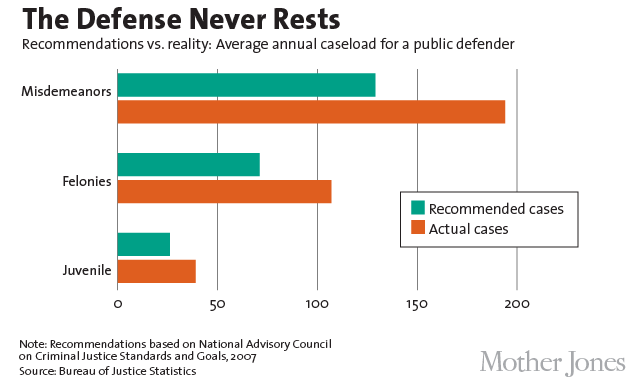

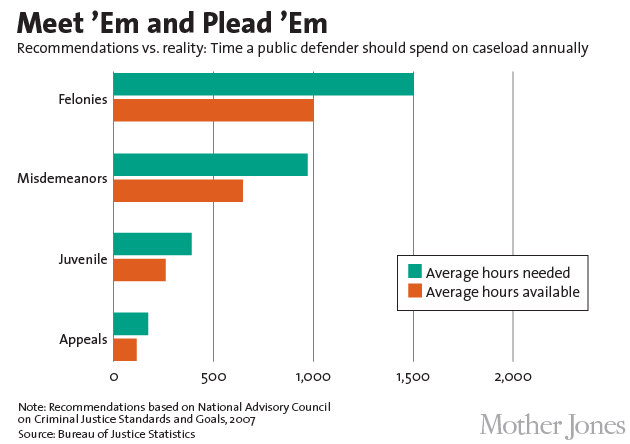

- The American Bar Association and the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals recommends caseload caps at 150 felony cases or 400 misdemeanor cases per full time attorney. But the 60 public defenders on Fresno’s staff carry caseloads of more than four times that amount.

- The county’s public defenders office has high turnover rates—50 attorneys quit between 2010 and 2014—and new hires are often inexperienced.

- Minorities make up about 70 percent of those arrested in Fresno. The ACLU claims that immigrants are often instructed to plead guilty without being told how it might affect their immigration status.

“What is happening in Fresno is significant,” says Jonathan Rapping, a lawyer and legal defense advocate who founded Gideon’s Promise—an organization that provides training and support for public defenders who represent the poor. Rapping explains that though the ACLU case focuses specifically on the problems in Fresno, exposing problems at the county level can have a wide impact on addressing systemic issues on a national level. “Theses lawsuits force state systems to examine what they are doing.”

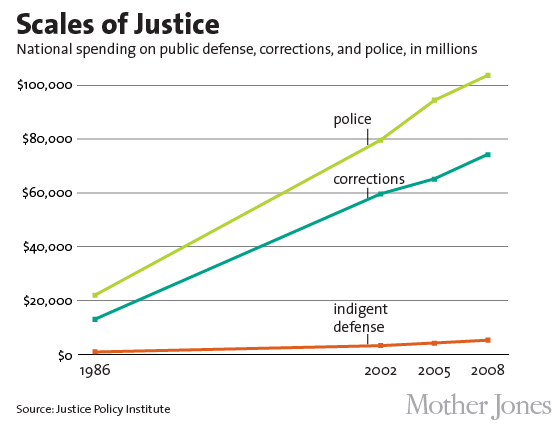

Data from US Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that public defenders are overworked and underfunded across the country and have been for years:

In 2013, the sequester—an $85 billion budget cut that reduced funding for agencies across-the-board—made these problems even worse. The already financially strapped public defenders offices had to tighten their budgets even further, and many offices had to lay off workers.

What’s more, because up to 60 percent of defendants in the United States rely on publicly-funded representation, the shortages have led to more incarcerations. “We are breaking state budgets by locking away people who don’t need to be locked away,” Rapping says.

“Lawsuits like this,” Rapping adds, “are really bringing to the public consciousness the fact that there are two very different systems of justice—One for people with money and one for people without money. I think that at our core as Americans we recognize that that just isn’t right.”