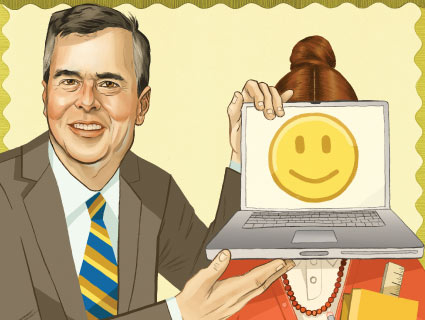

Kindergartener Hugo H. works on an iPad in his New Jersey school, which provides each student with their own device. Zach Frailey/AP

Students who share digital devices do better academically than their peers who have their own devices or no devices at all, a team from Northwestern University has found.

The study, conducted by communications Ph.D. candidate Courtney Blackwell, focused on three Chicago-area elementary schools. One school had iPads for each of its 100 kindergartners, another had roughly one iPad for every five students, and a third had no iPads at all. Blackwell found that the kindergartners who shared iPads scored 28 percent higher on a standardized literacy test at the end of the year compared to the beginning. Kids who had their own devices improved their scores by 24 percent, and those who had no devices at all increased their scores by 20 percent. Though the differences seem small, they are statistically significant, according to Blackwell.

Blackwell attributes the success of the sharing group to “the collaborative learning around the technology.” As an example, she pointed to an activity where students were instructed to find various shapes (squares, rectangles, circles, etc.) in their classroom and report their findings using their device’s microphone and recorder function. “In the shared classroom, two kids would share an iPad so there was much more talk and negotiation,” Blackwell told me. “If one kid pointed and said, ‘I found a square,’ another kid may say, ‘Oh, well that’s not a square—it’s a rectangle.'”

That collaboration enhances learning may seem obvious. But the implications of the study—that students don’t need their own digital devices—could be far-reaching, especially as many districts make major sacrifices in order to be able to afford technology. Take for example, North Carolina’s Mooresville Graded School District, which in 2009 decided to cut 65 staff members, including 37 teachers, in order to buy laptops for all of its students. (While the New York Times reported three years later that the district’s test scores had improved, it attributed the success to other factors as well.)

Probably the most infamous example of the intertwined relationship between tech and tests is the bungled Los Angeles Unified Schools District iPad initiative, which included a $1.3 billion contract with Apple and the testing and curriculum company Pearson. In the 2013-14 school year, the district, which is the second largest in the nation, began rolling out the program, which would outfit its 64,000 students with their own iPads. The effort was quickly deemed a failure—not only were there a lack of basic accessories like keyboards, but students were hacking their iPad security settings to they could spend class time scoping out Facebook and other off-limit sites. By the following summer, the district’s contract with Apple was annulled. Then, last October, the superintendent resigned amid rumors—which the FBI is currently investigating—that he and other administrators had connections with both Apple and Pearson that may have influenced the contract.

While Blackwell’s findings—that kids learn better when they engage with one another—aren’t earth shattering, they do serve as a reminder of the influence that the $7.9 billion educational technology sector holds over schools. It’s not clear yet whether the one-device-per-student approach is in the best interest of kids—or just the companies that make the devices and supply their content.