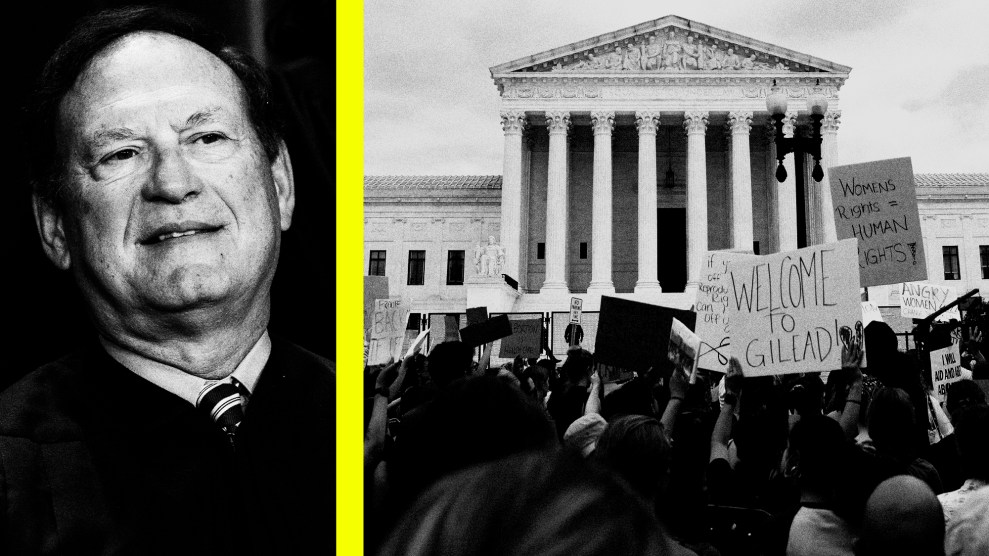

School kids hanging out in Baltimore's Inner Harbor neighborhood. <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/vox_efx/513775389/in/photolist-a9QEf7-a9QGj9-e6CoJE-e6wKsH-Mpewn-e6wKzK-e6CoxJ-3Y6PJW-nutyn3-nLF7W6-nutSVL-nuuggB-nLYfHt-nLNf7q-nLYxLM-nNKvCk-nLNcch-9iJRqL-9iFHyD-fvncuY-9iJRwq-9R13MS-dPdFeX-8qP25t-8qS7Nu-8qS86j-8qSbHu-8qS8HL-e6CoT7-o2fSaM-oiG5A7-e6wKkr-e6CoQC-e6CoHu-e6CoDW-e6wKvz-e6Covh-e6CoLC-e6wKLi-e6CoCA-e6CoN7-e6wKHM-e6CoAj-e6Cows-6w1fL9-9iFHAc-ojw4Ga-ojeqq4-ojtZBh-omh4hr"> Vox Efx</a>/Flickr

Many of the protesters venting their frustrations over the April 12 death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man who sustained fatal injuries while in Baltimore police custody, are equally fed up with the systemic failures that keep African Americans marginalized in Baltimore and elsewhere.

Consider the city’s public schools. President Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and even Orioles execs have spoken out about inequality in Baltimore, touching on problematic trends in the neighborhood schools Gray and his peers attended. And while we don’t know much about Gray’s time in high school (apart from the fact he played football), we were able to dig up some facts about his alma mater, Carver Vocational-Technical High School, and some of the other schools around the Mondawmin Mall, where rioting first broke out.

Demographics

- As of September 2014, 917 students were enrolled at Carver—98 percent black, 1 percent white. This lack of racial diversity qualifies Carver as an “apartheid school”—one where white students make up 1 percent or less of the student body, according to UCLA’s Civil Rights Project.

- Nearby Frederick Douglass High, the closest school to the mall, is also an apartheid school, and has the same percentage breakdown as above. Same with Maryland Academy of Technology and Health Sciences, a charter school near the mall.

- Apartheid schools, as you might expect, tend to have large numbers of low-income students. In 2011, the most recent year for which data was available, 79 percent of Carver’s kids qualified for free and reduced lunch. At Frederick Douglass, 83 percent did. This, according to the Civil Rights Project, “highlights the double segregation of students by race and class.”

ACADEMICS

- In 2011, nearly half of Carver’s teachers missed more than 10 days of school. At Walt Whitman, a mostly white school in Bethesda, with few low-income students, only 9 percent did.

- Carver now offers Advanced Placement classes—which it didn’t when Gray attended—and students have fared poorly. In 2014, out of 73 AP exams taken by Carver students only one student did well enough—scoring a 3 out of 5—to earn college credit. In the two years preceding, no student got more than a 2.

- In the 2013-14 school year, a little more than half of the students at Frederick Douglass graduated in four years. Out of nearly 1,100 students, only 73 took the SAT. Average score: 990. (A perfect score is 2,400*.)

- In the 2013-14 school year, only 27 percent of the students at Maryland Academy of Technology and Health Sciences, a charter school, were proficient in math, and just over 50 percent were proficient in reading.

DISCIPLINE

- During the 2011 school year, 88 Carver students received home suspensions. The wealthier Walt Whitman, with more than twice as many students, had 40. That disparity is consistent with US Department of Education data showing that black and Latino kids are disciplined at far higher rates than white students.

Gray had been out of school for years by the time he died, but the realities of his school system likely played a role in his trajectory. So says Georgetown University sociologist Peter J. Cookson, whose book Class Rules: Exposing Inequality in America’s High Schools posits that schools are instrumental in the institutionalization of racism and class stratification. Cookson points out that, while physical segregation plays a role, there are other factors at play, including disparities in the safety of buildings, extracurricular and support activities, quality of curriculum, funding (earlier this month Gov. Larry Hogan suggested cutting $35.6 million in funding to Baltimore City Public Schools), and the ability of schools to recruit and retain good teachers.

Dare we forget last fall’s viral video of a high-school teacher slamming a student into a row of lockers and saying, “I’ll kill you in here!” Yep, you probably know what’s coming: It was Carver High.

This post has been updated to include charter school stats as well.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified the numerical score of a perfect SAT.