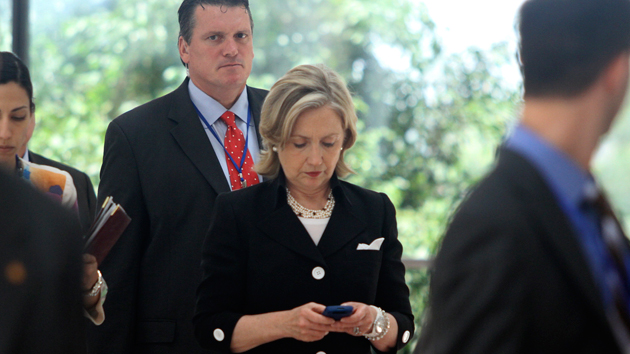

Bryan Smith/ZUMA

It is, unfortunately, an old and all-too familiar story. A Clinton, meaning Bill or Hillary, does something wrong (or possibly wrong). The media pounces; the Clinton antagonists of the right hit the warpath. Immediately, the Clinton camp and its supporters accuse the media and the conservative Clinton Hate Machine of trumping up a story to thwart the noble Clintons. Clinton spokespeople go into war-room mode. Resentful reporters grouse (privately and publicly) about the heavy-handed operators and obfuscators of Clintonland. And the right claims this latest fuss is a scandal that surpasses Watergate. Rinse, repeat.

The latest iteration of this Clinton-media dysfunctional spin cycle was triggered by the Hillary Clinton email kerfuffle that exploded last week. The Clinton camp’s handling of the controversy was a sign that Hillary and her gang are stuck in the Whitewaterish 1990s when it comes to communications strategy, relying on always-be-combating tactics predicated on self-perceived persecution. It’s bad news for anyone hoping that Hillary 2016 has learned from the miscalculations of the past.

Clinton’s use of a private email account to conduct secretary of state business and, just as important, her failure to preserve her messages in real-time within the department’s own record-keeping system were not, as Clintonites claimed, no biggie. Yes, Scott Walker had his own secret email scandal. And Jeb Bush, who tried to score political points by slamming Clinton, vetted his gubernatorial emails before releasing them to the public, while congratulating himself on his supposed devotion to transparency. (I’ve combed the Bush email archive for names and topics that ought to be there—and found obvious subjects absent.) So the Clinton defenders have a point when they gripe that the media is only obsessed with her email problem. But it is a small point. She was a Cabinet official. She had a duty to ensure that her records—which belong to the public, not her—would be controlled by the department, not by her private aides who operate her private server.

Moreover, the day she entered Foggy Bottom, she was a potential future presidential contender. She and her advisers should have assiduously tended to what was sure to be a sensitive matter. As the No. 2 political target in the nation and the top political celebrity (after the Obamas), Clinton could expect tremendous scrutiny from the press and from her Republican and conservative critics, who have never lost their taste for Clinton-bashing. For decades, she has seen what happens when a Clinton slips up. Fair or not, with this power couple, the volume knob does go up to 11. If not 12.

So it doesn’t matter what Colin Powell or Condi Rice did with their emails. Put aside Karl Rove’s use of a private GOP party email account when he was a White House official. Hillary Clinton screwed up. Voters, as the Clinton protectors argue, may not care about this. But the email controversy has breathed new life into the never-ending House GOP Benghazi crusade led by Rep. Trey Gowdy (R-S.C.), which before this had all but flat-lined. Now the probers and their conservative cheerleading squad can claim—with some basis in fact—that the public will never know for certain that Clinton and her lieutenants handed over every single email related to Benghazi. (She did turn more than 55,000 pages of emails to the State Department, but so far Clinton and her crew have not said how many pages, if any, were withheld.) So the bogus Benghazi inquiry has shifted from raking cold coals—after other Republican investigations debunked anti-Clinton conspiracy theories pushed by conservatives—to seeking the truth about Clinton’s emails. Clinton has given a gift to Gowdy’s almost-dead enterprise: It is now investigating a matter that can never be fully resolved. So Gowdy and conservatives will be free to say Benghazi questions remain because questions remain about Clinton’s emails.

Of course, Clinton and her emissaries cannot admit mistakes were made. I’m not privy to their private thinking, but it’s not hard to imagine a bedrock principle within this crowd: Don’t concede anything; don’t give our enemies anything. For instance, a Clinton spokesman told me that her emails had been preserved within the State Department. But that was not true. Some emails were retained within the system: those to and from other State Department officials. But as the State Department acknowledged to me, emails between Clinton and people outside the department related to official business were not captured by the State Department system. So the Clinton spokesman was attempting to convey a false impression. That happens all the time in politics. But political reporters who have been in this game for a while will tell you that many Clinton folks tend to engage in such tactics more aggressively (and confrontationally) than the average political op. And that ticks off journalists and perhaps causes them to scoff at Clinton credibility. (Take a gander at this epic email exchange between Clinton spokesman Philippe Reines and Gawker—if you can make it through it.)

Case in point: Lanny Davis. This Clinton loyalist has been in the news recently über-defending Hillary Clinton on the emails, and he’s been playing the same old cards: Everyone does it, she’s done absolutely nothing wrong, she’s been unfairly targeted by the media, yadda, yadda, yadda. This is not a new role for Davis. In the 1990s, when Senate Republicans were investigating fundraising improbities by the Clintons and the Democratic Party—such as fundraising at a Buddhist temple, offering White House coffees and overnights in the Lincoln Bedroom to big donors, and more—Davis was the White House lawyer who attended the hearings and tried to work the reporters covering the inquiry.

Though the Senate committee chaired by Republican Sen. Fred Thompson investigating the campaign finance scandal was hyping the case against Bill Clinton—suggesting that China had illegally funneled money to his presidential campaign—there were legitimate concerns about Clinton fundraising practices (when Terry McAuliffe was then the Clinton’s highly effective and prolific money chaser), as well as serious allegations about the excesses of the GOP’s money machine. Yet Davis, representing the White House, was hell-bent on denying any evidence of Clinton wrongdoing. It was absurd. There were days when the committee would reveal a memo clearly showing that the Democrats had done something untoward. In the hallway, Davis, in pitbull fashion, would insist with a straight face that the document did not say what it said, and he would self-righteously claim the GOP was wasting taxpayers’ money to wage this vendetta against the Clintons. Reporters soon began comparing him to Jon Lovitz’s SNL character, the pathological liar. (“Yeah, that’s the ticket.”) Anything Davis told us was totally discounted and dismissed. His reality denial discredited him—and, by extension, the White House.

At one point, I was talking to a Clinton aide working to develop the White House’s response to the investigation. Davis, I observed, was not helping them. He was alienating most everyone in the press. By refusing to concede any errors—even in the face of clear evidence—he was undermining White House credibility, generating ill will, and, perhaps worse, signaling that the Clintons didn’t care about the truth. Yeah, we know, this aide responded. But, he added, the Clintons were keen on Davis. They appreciated his moxie.

The Clintons survived that scandal. They had survived the Gennifer Flowers scandal, which was precipitated by a tabloid story that was probably more true than not but dismissed as trash by the Clinton gang. They had survived the Whitewater scandal, which had been triggered by a New York Times investigation (aided by Clinton foes in Arkansas) that Clintonites forever disparaged. They went on to survive the crazy Monica Lewinsky impeachment soap opera—which did reveal that there was a vast (okay, maybe not-so-vast) right-wing conspiracy set on demolishing the Clintons any way it could. And the whole damn media went along for that ride. But though the president had indeed received blow jobs from an intern in the White House and lied about it, the Clintons, as with the other scandals, still felt persecuted by their enemies and the media. It’s a bizarre relationship: (more or less) liberal Democratic politicians at cross swords with the media often slammed by the right as biased in favor of the left. (One theory thrown about by Clintonites during Bill’s presidency was that reporters were gunning for him because as the first Baby Boomer president he was a generational peer of many in the Washington press corps, and the scribblers and broadcasters viewed him with envy and, consequently, were suckers for the rightwing attacks on the couple.)

A sense of persecution seems too often to shape how the Clintons respond when they are in trouble, even when that trouble is self-inflicted. This testy, overly sensitive, secretive, and aggressive approach to the rest of the political-media world didn’t help Hillary Clinton during the 2008 campaign. Her campaign claimed she was being victimized by a Barack Obama-loving media, while her aides hurled a host of unfounded accusations and criticisms against Obama and his team. As Davis had accomplished a decade earlier, Hillary’s emissaries to the media alienated many reporters with their odd combo of thin-skinnedness and fact-stretching aggression. Did her bad relations with the media undo her campaign? Probably not. But it sure didn’t help.

For six years, Hillary Clinton, her husband, and their crew have had time to ponder and perhaps entertain a different approach. Certainly, they know that many of the flaws of 2008 and earlier years should not be repeated (such as the hiring of Mark Penn and Dick Morris). Yet can they break free of the vicious triangle—the Clintons, their real enemies, and the media—and drop the paranoia (even if it is justified at times) and disrupt this decades-long cycle of dysfunction? It may well be that it’s just too late for this pack to learn new tricks. Which would mean we’re all doomed, in a lousy version of Groundhog Day, to watch and participate in this dispiriting dynamic ad nauseam until we mercifully reach Election Day—or, if she wins, the last day of Hillary Clinton’s presidency.