Update, July 13, 2015: The City of New York has agreed to pay $5.9 million to settle the wrongful death complaint filed by Eric Garner’s family members, according to the New York Times.

When police officers kill unarmed citizens they are rarely charged, let alone convicted of a crime. The victims’ families often turn to civil complaints against the police, as is currently the case in New York City, Cleveland, and Los Angeles, where wrongful death and other civil rights claims filed in the wake of officer-involved killings could result in payouts tallying in the millions of dollars. Still, the police officers involved are likely to suffer no financial pain. That’s because in the vast majority of such cases, whether they are settled or go to court, the officers don’t pay a dime.

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer is currently reviewing civil claims brought by the family of Eric Garner, the 43-year old Staten Island man who died in July 2014 after NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo put him in a chokehold. The $75 million worth of claims include wrongful death, assault, pain and suffering, and negligent hiring and training by the NYPD. But if the city decides to settle the case with the Garner family, a spokesperson for the comptroller told Mother Jones, Pantaleo will pay nothing.

Instead, taxpayers will shoulder the cost. Between 2006 and 2011, New York City paid out $348 million in settlements or judgments in cases pertaining to civil rights violations by police, according to a UCLA study published in June 2014. Those nearly 7,000 misconduct cases included allegations of excessive use of force, sexual assault, unreasonable searches, and false arrests. More than 99 percent of the payouts came from the city’s municipal budget, which has a line item dedicated to settlements and judgments each year. (The city did require police to pay a tiny fraction of the total damages, with officers personally contributing in less than 1 percent of the cases for a total of $114,000.)

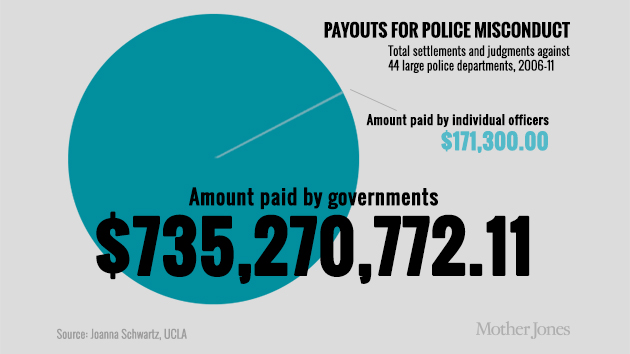

This scenario is typical of police departments across the country, says the study’s author Joanna Schwartz, who analyzed records from 81 law enforcement agencies employing 20 percent of the nation’s approximately 765,000 police officers. (The NYPD, which is responsible for three-quarters of the cases in the study, employs just over 36,000 officers.) Out of the more than $735 million paid out by cities and counties for police misconduct between 2006 and 2011, government budgets paid more than 99 percent. Local laws indemnifying officers from responsibility for such damages vary, but “there is little variation in the outcome,” Schwartz wrote. “Officers almost never pay.”

Even if the Garner family were to take its case to court and prevail, the chances of Pantaleo paying are extremely remote. The 34 cases in the study where New York City officers paid some amount were all resolved with settlements, Schwartz notes, not with judgments in court, which few such cases ever reach.

Moreover, Pantaleo remains protected from financial liability despite that he was the subject of at least three civil rights lawsuits before the death of Garner. One case, in 2013, involved two men from Staten Island who alleged that Pantaleo and three other officers unlawfully stopped and ordered them from their vehicle, then pulled down their pants and “touched and searched their genital areas, or stood by while this was done in their presence.” The city paid a $30,000 settlement to the plaintiffs, while the officers paid nothing. Two other lawsuits stemming from a 2012 incident alleged that Pantaleo and other NYPD officers falsely arrested and imprisoned two men, according to federal court records. (Both of those cases are pending.)

Families of unarmed victims shot dead by police have recently filed claims in Cleveland, where police killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice over a pellet gun, and in Los Angeles, where officers shot 25-year-old Ezell Ford three times after he allegedly tried to reach for an officer’s gun. According to Schwartz’s study, Cleveland and LA both paid out millions in police misconduct claims between 2006-11. (See table below.) During that same period, St. Louis—which has become a focal point for police brutality ever since an unarmed Michael Brown was gunned down in the suburb of Ferguson in August 2014—paid out $2.7 million for civil rights claims against police. (The city did not provide Schwartz with details on how much if any of that sum officers were required to pay.) Brown’s parents are considering filing a wrongful death claim but remain undecided about doing so, their attorney Anthony Gray told Mother Jones.

In the past, the Supreme Court has ruled that police officers should be afforded “qualified immunity” from civil rights claims brought by citizens—the risk of legal exposure could deter officers from carrying out their duties, the court has held—except in cases where an officer has violated “clearly established law.” Yet, in other cases the Supreme Court has ruled that municipalities should not be liable for damages incurred by its employees, and that punitive damages can’t be awarded against cities. In a 1981 majority opinion, Associate Justice Harry A. Blackmun stated that if municipalities were held liable for civil claims, it could lead to tax hikes or “a reduction of public services for the citizens footing the bill. Neither reason nor justice suggests that such retribution should be visited upon the shoulders of blameless or unknowing taxpayers.” But in Schwartz’s view, cities requiring so few officers to pay even for punitive damages “goes against the spirit of that decision.”

And the full extent of the costs to taxpayers remains unclear, she notes. Out of the 140 municipal, county, and state law enforcement agencies that Schwartz requested records from, only 44 provided extensive data, as detailed in the table below. While additional police departments provided some information on misconduct, the data either did not specify civil rights cases or was too incomplete to analyze.