Scott Panetti, shortly after he shaved his head, donned fatigues, and shot his in-laws to death.

Almost no one wants to see Scott Panetti put to death. Conservatives such as Ron Paul and Ken Cuccinelli and evangelical leaders have spoken up on his behalf. The European Union has protested his pending execution, which is temporarily on hold thanks to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. Even some of Panetti’s victims don’t believe he should be killed by the state.

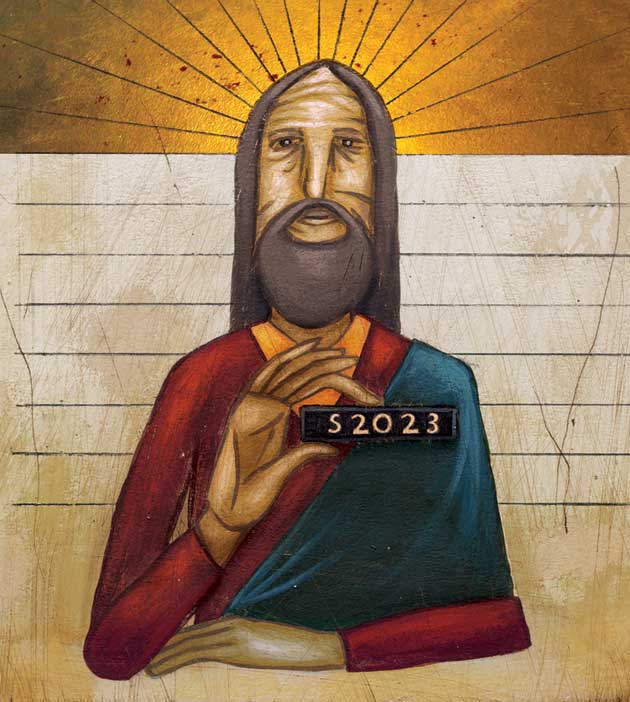

The Supreme Court has ruled that states cannot execute a mentally ill person who lacks a rational understanding of the nature of his punishment. Panetti fits that standard: He insists that Texas wants to kill him to prevent him from preaching the Gospel. And yet the state has gone to great lengths to ensure that Panetti gets the needle. Right up until December 3, when the 5th Circuit temporarily halted Panetti’s execution with hours to spare, the state has deployed legal gamesmanship that seems more appropriate for patent litigation than a death penalty case.

Panetti’s schizophrenia has been apparent since 1978, when he was 20 years old. By 1986, the Social Security Administration had declared him disabled by his brain disorder and therefore eligible for federal benefits. Six years later, after a series of hospitalizations and bizarre incidents—in one case he buried demon-possessed furniture in his yard—Panetti shot and killed his in-laws, Joe and Amanda Alvarado.

His criminal case was a theater of the absurd from the outset, thanks to a series of puzzling legal decisions by Texas and federal judges. It began when Kerr County District Judge Stephen Ables, still on the bench today, permitted Panetti to represent himself at trial over the objections of the state. He showed up wearing what a friend of the family later described as a 1920s-era cowboy outfit: “It looked idiotic. He wore a large hat and a huge bandana. He wore weird boots with stirrups, the pants were tucked in at the calf,” she testified in an affidavit. “He looked like a clown. I had a feeling that Scott had no perception how he was coming across.” Thus clad, standing before the jury, Panetti called himself “Sarge” and rambled incoherently for hours with little interruption from the judge—who did, however, argue with the defendant over the relevance of belt buckles and whether he could discuss the TV show Quincy. As part of his defense, Panetti issued a stream-of-consciousness description of his crime, from Sarge’s perspective:

Fall. Sonja, Joe, Amanda, kitchen. Joe bayonet, not attacking. Sarge not afraid, not threatened. Sarge not angry, not mad. Sarge, boom, boom. Sarge, boom, boom, boom, boom. Sarge, boom, boom.

Sarge is gone. No more Sarge. Sonja and Birdie. Birdie and Sonja. Joe, Amanda lying kitchen, here, there, blood. No, leave. Scott, remember exactly what Sarge did. Shot the lock. Walked in the kitchen. Sonja, where’s Birdie? Sonja here. Joe, bayonet, door, Amanda. Boom, boom, blood, blood.

Demons. Ha, ha, ha, ha, oh, Lord, oh, you.

The jury, not surprisingly, found him guilty of capital murder. They subsequently sentenced him to die.

Thus began the long, slow appeals process—Panetti at one point tried to fire his lawyers and abandon his appeals, but a judge finally declared that he was mentally incompetent to make such a choice. He was nearing execution in 2004, when his lawyers asked for a hearing to determine his mental competency, leading to more appeals and, ultimately, a hearing by the US Supreme Court.

For a moment it looked like Panetti’s legal saga might be over. In 2007, the Supreme Court ruled that he was clearly mentally ill, and that the lower courts had used too stringent a standard to assess his competency. Justice Kennedy wrote: “He suffers from a severe, documented mental illness that is the source of gross delusions preventing him from comprehending the meaning and purpose of the punishment to which he has been sentenced.” The case went back to US District Court Judge Sam Sparks, who, four years earlier, had found Panetti sane enough to execute. Sparks held a new hearing to assess Panetti’s competency under the new standard, but came to the same conclusion, despite considerable testimony about Panetti’s mental-health history and current delusions. The 5th Circuit upheld Sparks’ ruling, as did the Supreme Court.

Judges had another chance to end the charade in 2008, after the Supreme Court made it harder for mentally ill people to represent themselves at trial. Filings in that case actually cite Panetti as a cautionary tale. The opinion helped ensure there wouldn’t be any more cowboy clowns representing themselves in capital cases, but when Panetti’s lawyers tried to benefit from the ruling, Texas and federal judges threw out his case on a technicality.

One of them was none other than Sparks, who spent more than 100 pages explaining why the court “does not believe that Panetti’s mental illness rendered him incompetent to represent himself.” Although Panetti chose his jurors by flipping a coin, Sparks argued that he “made meaningful decisions” during jury selection. The fact that he took notes and dismissed one woman because she was seven months pregnant demonstrates his understanding of the legal system, Sparks wrote.

Bolstered by these decisions, the state continued its all-out quest to kill Panetti in the face of deep public opposition. Many of the prosecutors’ recent actions are detailed in legal filings with the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. Perhaps the most audacious came this past October, after the Supreme Court refused to hear Panetti’s latest appeal. The state court set an execution date, and while the prosecutors and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice were aware that the death warrant had been signed, no one bothered to tell Panetti’s lawyers. They learned about it two weeks later in the Houston Chronicle.

This delay left the lawyers scrambling, with just one week to file what’s known as a Ford claim, a request for a hearing to determine whether an inmate is too insane to execute. Ford claims, based on the Eighth Amendment’s cruel and unusual punishment clause, which prohibits the execution of mentally ill people, may not be filed until the death warrant is signed.

The Texas attorney general’s office insisted in legal filings that state law doesn’t require it to notify the defense of an impending execution. Which is true. But the Texas Lawyer’s Creed arguably requires notification. This voluntary professional code of ethics instructs lawyers, among other things, not to take action that “unfairly limits another party’s opportunity to respond.”

It’s unclear whether state officials told Panetti himself that he was set to die. Ellen Stewart-Klein, the Texas assistant attorney general handling the case, did not respond to a request for comment. Regardless, notes Kathryn Kase, one of Panetti’s lawyers, “I think in a case where you have a man with 36 years of mental illness, notice to that man is not sufficient.”

Panetti’s recent filings show that Texas courts have refused multiple requests to appoint him a lawyer for his most recent appeals. (The Constitution only guarantees capital defendants a lawyer up through their first appeal.) In practice, this means Panetti’s current lawyers won’t be paid for handling the appeals filed since his death warrant was issued. The courts also have denied Panetti funding to hire the experts he needs to prove he’s not sane enough to be executed. Just to get a Ford hearing, his lawyers must present up-to-date evidence of his incompetence, which requires a psychiatric assessment. And most forensic psychiatrists don’t work for free.

Yet the state has brought in its own experts to press the case against him. In early December, prosecutors filed an affidavit from Dr. Joseph V. Penn, director of mental-health services in the correctional managed care division of the University of Texas Medical Branch. Penn swore that Panetti’s condition hadn’t changed since his competency hearing in 2007. The prisoner, he said, hadn’t asked for any medication for his symptoms—which was no surprise, he added, since Panetti’s prison medical records show no diagnosis of mental illness. And while Panetti might be “hyper-religious,” his condition isn’t severe enough to warrant treatment with drugs. The affidavit supports the state’s long-standing assertion that Panetti is simply an alcoholic or drug addict faking his 36-year history of mental illness.

Panetti’s medical history contradicts that assessment. For most of the 17 years he’s been incarcerated, he has refused anti-psychotic drugs. Shortly before he went to trial, he had a revelation that he was a “born-again April fool” who “depended on the Lord to do for me what medicine wasn’t doing.” In 2012, according to records turned over to his lawyers, Panetti began growing more paranoid, suspicious that the prison was tampering with his food and conspiring with gangs to persecute him. After nearly 12 years without a write-up, he started acting aggressively toward staff, even throwing urine on a guard.

Over the past two years, records show, Panetti asked for mental-health care on three occasions. On the most recent, in November 2013, he requested an appointment with a psychiatrist, telling a mental-health staffer that he thought he might need to go back on his meds because preaching the Bible wasn’t keeping the voices in his head at bay anymore. It’s unclear whether he got treatment, because the state hasn’t turned over any medical records since Panetti made that request.

The state claims no such records exist because Panetti hasn’t needed mental-health care. His lawyers counter that the state is either hiding the records or officials refused to treat him because to do so might help his case.

At least twice in the past month, without informing his lawyers, the state has tried to evaluate Panetti for mental illness, according to Penn’s affidavit. (Panetti refused both attempts.) Panetti’s lawyers view this as a violation of due process. The state, they argue, only sought to evaluate him after the execution date was set, “leading to the inescapable conclusion that the efforts were made for the purpose of creating evidence to contest Mr. Panetti’s competency in the Ford proceedings, not for the purpose of treating him.”

Texas has resorted to other brass-knuckle tactics, also detailed in the 5th Circuit filings. On Election Day, corrections officials recorded a visit between Panetti and his parents, who are nearly 80, and quoted from it in court filings to argue that he is “lucid and intelligent” because he was able to talk about politics.

They conveniently left out the portion, two minutes in, where Panetti starts rambling about the time in Wisconsin when he was grooming steer with former CIA agent Valerie Plame. “I don’t know if I was just hearing voices about Valerie Plame, Mom,” he says. “But it was her. But I sure got a pretty good indication that indeed it was.”

Panetti would be dead now but for the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals—its stay of execution a rare moment of sanity in a legal process that has made the Texas courts, if such a thing were possible, even more of an international pariah than before. Now it looks like Panetti may get a full hearing on his competency in federal court. There’s no guarantee he’ll prevail. He was pretty sick the last time the federal courts evaluated his mental state, and they ruled against him anyway.

Even a finding of incompetency would be a temporary salvation. Given appropriate medical treatment, Panetti could potentially become competent enough to be again eligible for execution, forcing him (and his lawyers) to choose between insanity and death. But for the moment, the 5th Circuit’s decision has bought him time, and a competency hearing represents his best shot to convince a judge that he never belonged so close to death in the first place. As Kase puts it, “The 5th Circuit saved Texas from itself.”