Amber Hunt/AP Images

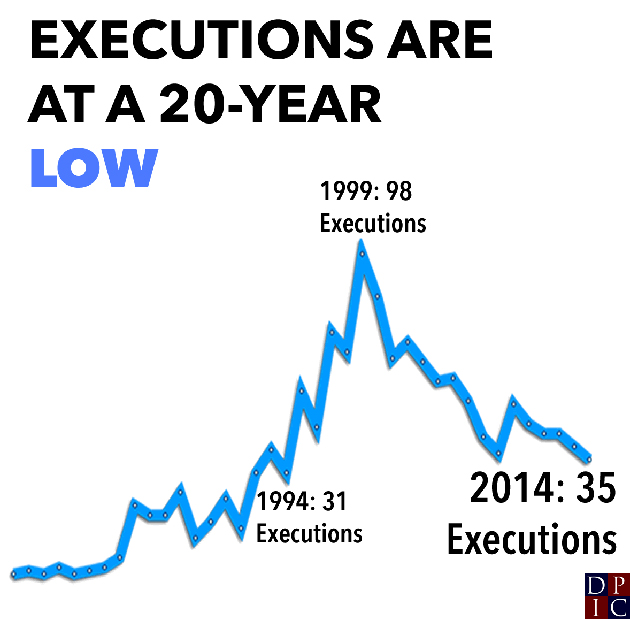

There’s some encouraging news this week in the usually gloomy realm of criminal justice. According to a new report from the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), there were fewer executions this year than in any year since 1994—and fewer new death sentences imposed than any year since 1974. That may be of little comfort to the family of Robert Wayne Holsey, a low-functioning man whose severely alcoholic court-appointed lawyer sealed his ultimate fate—Georgia executed him earlier this month—but the numbers are certainly dwindling. In 2012, states put 43 people to death. In 2013, the number was 39. This year, it’s down to 35.

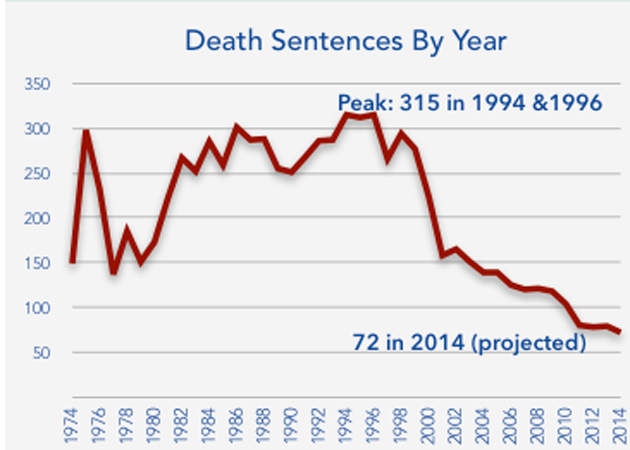

Perhaps more encouraging for foes of capital punishment: Only 72 new death sentences were imposed this year (a measure the DPIC considers a more accurate indicator of the trend). That’s a 77 percent decline since 1996, as more and more states have offered juries the option of imposing a sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

In addition, an increasingly smaller group of states accounts for the majority of executions. Seven states put prisoners to death this year (down from 20 just 15 years ago)‚ but just three of them—Florida, Missouri, and Texas—accounted for 80 percent of all the executions. The number of states that sanction the death penalty may be waning, too. In 2014, the governors of Colorado, Oregon, and Washington all imposed moratoria. And for what it’s worth, 2014 was the first year since 1997 that Texas didn’t lead the country in executions. (It tied with Missouri, at 10 apiece.)

Aside from the continued decline in public support for capital punishment—just over half of Americans were for it in 2014, as opposed to nearly two-thirds in 2011—some new factors may have contributed to this year’s numbers. Botched executions in Ohio, Arizona, and Oklahoma shed light on the untested drug cocktails states are now using for lethal injections, after European drugmakers cut off their supplies. Following widespread press coverage of these gruesome execution attempts—some of which appeared to violate the Eighth Amendment’s protection from cruel and unusual punishment—Oklahoma and Ohio halted executions for the rest of the year. (In response to the mishaps, the Justice Department is expected to release a major report next year.)

We’ve also seen increased scrutiny this year of states’ willingness to execute the mentally ill or intellectually disabled. Earlier in the year, the Supreme Court ruled in Hall v. Florida that Florida’s fit-for-execution standard—merely having an IQ exceeding 70 was enough—violated standards of decency. And the case of Scott Panetti, a schizophrenic man that Texas is determined to execute, put that state’s low standards on international display. (A federal court has temporarily stayed Panetti’s execution, a move even prominent conservatives have supported.)

Major battles lie ahead for death penalty opponents. More than 3,000 people are still on death row and 30 executions have been scheduled for 2015. Fourteen states, including some the ones that botched their executions, have pursued legislation that would shroud many aspects of the execution process in secrecy—particularly the details about what’s in their lethal cocktails.

But momentum against the death penalty is strong. “Overall, the decline in the use of the death penalty has been going on for 15 years, and is likely to continue,” explains Richard Dieter, the executive director of the DPIC and an author of the new report. “For the public, the death penalty has already receded as a significant part of the criminal justice process.”