Don’t expect much drama when Louisiana voters go to polls again next month—especially in the 6th Congressional District. After fending off an eclectic field of challengers, Republican Garret Graves is facing former Democratic Gov. (and convicted felon) Edwin Edwards in a runoff election. Graves, who resigned his job as director of the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority in February, is expected to win handily in a district Mitt Romney carried by 30 points.

As one of GOP Gov. Bobby Jindal’s top lieutenants and a former staffer for some of Washington’s most high-powered politicians-turned-lobbyists, Graves has a base of political support that would be the envy of many in his class. But that’s not what makes him unique. Rather, what sets him apart is that he’s one of the only incoming Republican congressmen to seriously grapple with the effects of climate change.

Graves’ chief accomplishment as Jindal’s “coastal czar” in Baton Rouge was the 2012 Louisiana Coastal Master Plan, a $50 billion scheme to shore up the state’s rapidly disappearing coastline against erosion and rising sea levels. The proposal was hailed at the time for its scope, and Graves has won plaudits from some of Jindal’s most consistent critics for his work. “It remains unfunded, but all acknowledge that it is based on science, not politics,” wrote the New Orleans alt-weekly, the Gambit, in an editorial when Graves stepped down. “That alone is a significant accomplishment.” A coalition of environmental advocacy groups hailed Graves as an “invaluable voice” for coastal protection, and one of those groups, the Environmental Defense Fund, has spent six figures to help get Graves elected.

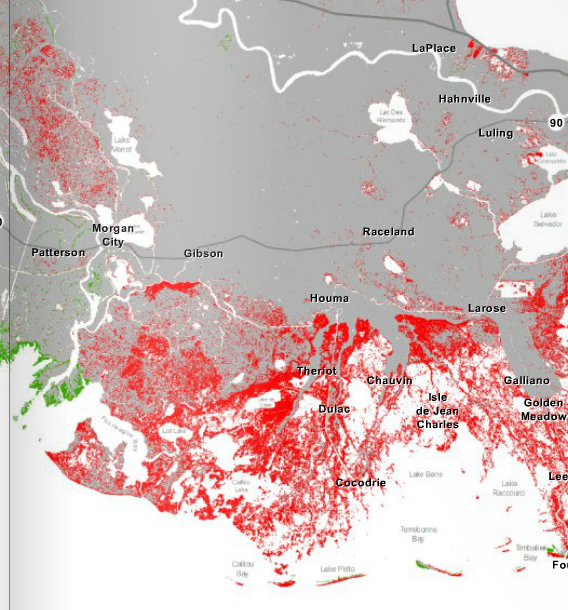

The Master Plan is based on the assumption that sea levels in South Louisiana will rise somewhere between five inches and 2.1 feet over the next 50 years. “Climate change was central to our analysis, given coastal Louisiana’s vulnerability to increased flooding and the sensitivity of its habitats,” the report explains. Although it doesn’t assert that the changes are man-made, it doesn’t back away from those who do. “The science behind this is extensive,” it declares, noting emphatically that “sea-level rise will accelerate in the next century.” The primary source behind this: the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which has been pilloried by the right as a cabal of pseudoscientific alarmists. The plan also predicts an economic disaster if the state doesn’t act—Graves’ document forecasts a 1,000 percent jump in annual flood- and storm-related damages by 2061, to $24.1 billion each year.

The 6th District, which extends from Baton Rouge to the Gulf, will be hit especially hard according to Graves’ projections. Much of its southwestern tail will become open water:

Graves is pragmatic in the sense of accepting the numbers coming out of the scientific community. “Our Master Plan looked at the measured rise of seas that we’ve experienced over recent years,” he told me after a candidate forum in September. “We’d be idiotic to not factor that into future change. So, it’s in the Master Plan.”

But when it comes to acting on the scientific consensus, it has been a different story. At the same candidate forum, he thanked the Koch brothers, who have bankrolled a network of climate-denying groups, for contributing to his campaign through their PAC. And he rejected the premise of the question when I asked him if he felt Congress should be doing more on climate change, arguing that “the deltaic process in the Mississippi River” is the real key to saving the state, not greenhouse gases. “The climate’s always changed,” he said, echoing the chorus of the denier caucus in Washington. In an interview with the Baton Rouge Advocate, he contended that scientists hadn’t fully determined whether humans were a contributing factor.

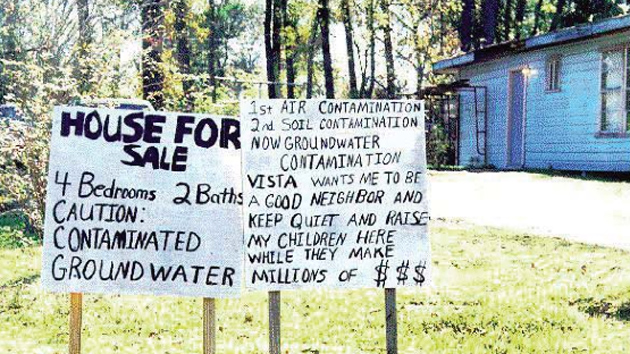

The biggest tell of how he’ll act in Congress may have come last summer, when the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, a regional board established by the state after the Hurricane Katrina, announced it was planning on filing a lawsuit against 100 oil and gas companies. The board alleged that the companies’ operations had increased flood-protection costs by eroding the coast. Graves’ Master Plan itself contends that the state’s never-ending network of canals and pipelines has taken “a toll on the landscape, weakening marshes and allowing salt water to spread higher into coastal basins.”

But Graves condemned the lawsuit immediately as little more than the work of a “greedy trial lawyer,” and he joined with Jindal in a yearlong crusade to help kill it. Pro-lawsuit flood board members were replaced by the governor, and with Graves’ support, the Legislature passed a bill last spring, written with the help of oil industry attorneys, that would retroactively prohibit flood boards from taking legal action. (The law, signed by Jindal, was declared unconstitutional by a judge last month and is heading to the state Supreme Court.)

Barring a spectacular upset, Graves will represent a kinder, fresher approach to climate issues than firebrands like Sen. David Vitter (R-La.), his former boss, who once dismissed climate science as “ridiculous pseudoscience garbage.” Environmental groups have found a rare Republican they think is in their corner. So what happens when the congressman has to choose between Koch and coast? They’ll find out soon enough.