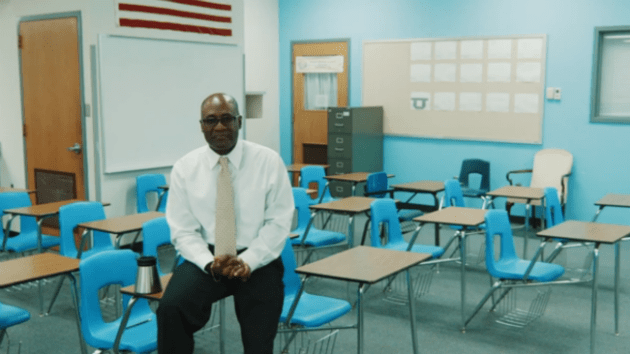

Texas HD 113 candidate Milton Whitley. <a href="http://www.whitleyfortexas.com/">Whitley for Texas</a>

Milton Whitley’s gift to Texas was called twisted yam on a stick. You take a yam, cut it into a spiral, deep fry it, cover it in butter, smother it in sugar, coat it in cinnamon, eat. Is it healthy? Of course it’s healthy—yam is a superfood. The final product was a finalist at the 2009 Texas State Fair, before losing out to the eventual winner, deep-fried butter.

A native of Dallas County, Whitley started off as a catfish cook and worked his way up the comfort food chain to an appearance on national television presenting Oprah and Gayle with a homemade sweet potato pie. He now teaches science at a public school. But last year he set his sights on something more daunting than the fried-food contest at the state fair—getting elected to the Texas Legislature as a Democrat. Whitley, who’s running in the Dallas-area 113th state House district, is one of a dozen candidates selected as part of a trial program for Battleground Texas, the Democratic organizing project launched last spring by a cast of Obama campaign veterans who are hoping to turn the nation’s largest red state blue.

Battleground’s biggest investment is in the governor’s race, where it threw its resources behind the campaign of state Sen. Wendy Davis. But Battleground has also invested heavily in a slate of 12 “Blue Star Project” candidates, giving them access to the group’s army of volunteers and reams of field data, and working with first-time nominees to bring them up to speed. And with Republican Greg Abbott holding a steady double-digit lead over Davis in the polls, it’s the performance of candidates like Whitley, in lower-profile state Legislature and judicial races from the Rio Grande Valley to Fort Worth, that might offer the clearest Election Day barometer of the group’s success.

Before Battleground, Whitley says, Dallas Democrats—Milton Whitley included—”were good at eating donuts, but the organization wasn’t there.” In 2012, with President Obama—normally a major boost to Democratic turnout—on the ballot, Democrats failed to field a candidate in Whitley’s district. But the Obama veterans’ arrival “turned tea-sippers into activists,” Whitley says. Now he’s door-knocking six days a week in a golf cart—souped up, in true Texas style, with a cab in the back and off-road capability.

Davis’ 2013 filibuster of an anti-abortion bill also helped galvanize Texas Dems—including several of Battleground’s top candidates. Whitley drove to Austin the morning after the filibuster to protest the bill (which was passed in a second special session) and decided to run for office shortly thereafter. Kim Gonzalez, a prosecutor in South Texas, says the 11-hour talkathon compelled her to abandon her goal of becoming district attorney and enter politics instead. “It’s not just an abortion issue—we have lost three health care clinics [in the district], none of which provided abortion services,” she said, pointing to the bill’s collateral damage.

“Great people don’t want to run unless they feel there’s an infrastructure to support them, but it’s hard to get great infrastructure without great candidates,” Jenn Brown, Battleground’s executive director, said in an interview last week in the Jim Wright Conference Room at the group’s Fort Worth headquarters. “So what we were going to do was just start organizing and then the hope was in 10 years—or 6 years, or however long—we would convince someone great that we had a big enough infrastructure that was ready to support them and they should run.”

Now that Battleground has its candidate, Brown is downright hyperbolic. “I think in a lot of ways, Wendy Davis has restored democracy in Texas.” she says.

But many of Battleground’s down-ballot campaigns underscore the headwinds Democrats face. Leigh Bailey, another Battleground-backed candidate, is seeking a GOP-held seat that encompasses the north Dallas suburbs. It’s the kind of race Democrats will need to start winning for their statewide dreams to take flight. But the district also includes Highland Park, an oil-rich suburb that’s home to some of the biggest donors in Republican politics. (Former president George W. Bush is a resident.) In 2012, the current Republican state representative, who is retiring at the end of the year, won reelection with 80 percent of the vote. The runner-up was a libertarian—Democrats didn’t field a candidate.

In heavily Latino South Texas, Democrats are hoping to take back a seat that has come to symbolize the party’s plight. Gonzalez, the prosecutor, is taking on Republican J.M. Lozano, a state representative who switched parties in 2012. By Lozano’s own admission, his move came largely at the urging of George P. Bush, the nephew of the 43rd president, who founded a group called Hispanic Republicans of Texas to recruit Latino conservatives to run for office. (Bush, whose mother is from Mexico, is running for state land commissioner this year.) In turn, Lozano received donations from arguably the state’s most powerful political action committee, Texans for Lawsuit Reform, which advocates for limiting lawsuits on behalf of its corporate funders. It was a marked shift—Lozano first won the seat by skewering his opponent as a stooge of tort reformers.

The limited scope of Battleground’s first campaign—barring a Davis upset, that is—is a testament to just how high the bar is for success in Texas, and just how little low-hanging fruit there is to pluck. Republicans carefully drew legislative districts to reduce the number of competitive races and consolidate GOP gains. And the historically low rate of voter participation among Democratic-leaning demographics in Texas (there are as many as 800,000 nonregistered voting-age citizens in the Houston area alone, according to one estimate) means that Battleground will spend much of its first election cycle getting back to the starting line—all while fighting the effects of new Republican measures like voter ID laws designed to depress turnout.

Even if Democrats run the table in the 12 districts they’ve targeted, they’ll still find themselves in the minority in Austin—by about 20 seats.