Over 100 people showed up on Tuesday night at the first Ferguson City Council meeting since Michael Brown’s killing, and unreasonable court fees were a major complaint. Ferguson officials proposed scaling back the myriad ways small-time offenders can end up paying big bucks—or worse. Community activists are optimistic about the proposed changes, but as it turns out, imposing punitive court fines on poor residents is a major source of income for a number of St. Louis County municipalities.

How bad is the current system? Say you’re a low-income Ferguson resident who’s been hit with a municipal fine for rolling through a stop sign, driving without insurance, or neglecting to subscribe to the city’s trash collection service. A look at the municipal codes in Ferguson and nearby towns reveals how these fines and fees can quickly stack up.

To start, you might show up on time for your court date, only to find that your hearing is already over. How is that possible? According to a Ferguson court employee who spoke with St. Louis-based legal aid watchdog ArchCity Defenders, the bench routinely starts hearing cases 30 minutes before the appointed time and even locks the doors as early as five minutes after the official hour, hitting defendants who arrive just slightly late with an additional charge of $120-130.

Or you may arrive to find yourself faced with an impossible choice: Skip your court date or leave your children unattended in the parking lot. Non-defendants, such as children, are permitted by law to accompany defendants in the courtroom, but a survey by the presiding judge of the St. Louis County Circuit Court found that 37 percent of local courts don’t allow it.

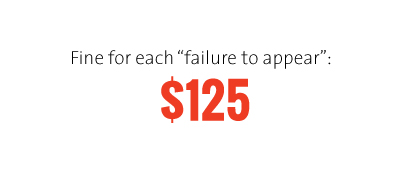

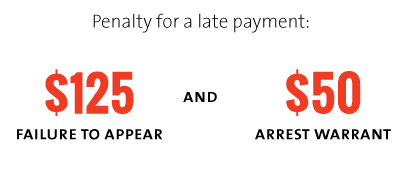

Coming to court has its own pitfalls, but not the ones many people fear. It’s a common misconception among Ferguson residents—especially those without attorneys—that if you show up without money to pay your fine, you’ll go to jail. In fact, you can’t be put behind bars for inability to pay a fine, but you can be sent to jail for failure to appear in court (and accrue a $125 fee). If you miss your court date, the court will likely issue a warrant for your arrest, which comes with a fee of its own:

At this point, you owe your initial fine, plus fines for failure to appear in court and the arrest warrant. Thomas Harvey, executive director of ArchCity Defenders, explains that if you’re arrested, your bail will likely equal the sum of these fines. Ferguson Municipal Court is only in session three days a month, so if you can’t meet bail, you might sit in jail for days until the next court session—which, you guessed it, will cost you.

Once you finally appear in court and receive your verdict, your IOU is likely to go up again.

Can’t pay all at once? No problem! Opt for a payment plan, and come to court once a month with an installment. But if you miss a date, expect another $125 “failure to appear” fine, plus another warrant for your arrest.

Court fines for minor infractions tend to snowball. For example, drivers accumulate points for speeding, rolling through stop signs, or driving without insurance. You can pay to wipe your record, which is pricey. If you can’t afford to, and rack up enough points, your license will be suspended and your insurance costs will probably jump. Need to get to work? If you’re caught driving with a suspended license, your court fines increase, you gain more points, and your suspension is lengthened. That’s how rolling through a stop sign could end up costing you your job, messing up your degree plans, and more.

In a county like St. Louis, which consists of 81 different municipal court systems, it’s easy to end up with fines and outstanding warrants in multiple towns. Harvey has seen his clients bounce from jail to jail, and says there’s even a local name for this: the “muni-shuffle.”

“Every handful of months, there’s some awful thing that happens as a result of someone being arrested on multiple warrants,” says Harvey. Last year, a 24-year-old man in Jennings, another city in St. Louis County, hung himself after he couldn’t get out of jail for outstanding traffic warrants. “They can’t get out, and they know they’re not going to get out,” says Harvey. In Ferguson, he explains, residents are caught in cycles of debt that stem from three main infractions: driving without insurance, driving with a suspended license, and driving without registration.

So what happens to all that cash? In Ferguson, as in thousands of municipalities across the country, it goes toward paying city officials, funding city services, and otherwise keeping the wheels of local government turning. In fact, fines and court fees are the city’s second-largest revenue source. Last year, Ferguson issued 3 warrants for every household—25,000 warrants in a city of 21,000 people.

“Ferguson isn’t an outlier,” says Alexes Harris, sociology professor at University of Washington and author of the upcoming book Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Permanent Punishment for Poor People?. Similar measures play out in jurisdictions across the country. “All you have to do is show up in court and watch what happens.”

The good news is that this week, under pressure from local activists, the Ferguson City Council announced plans to eliminate some of the most punitive fees, including the $125 failure to appear fee and the $50 fee to cancel a warrant. Of course, nothing is set to change elsewhere in St. Louis County. But eliminating some of the most egregious fees in one town, says Harvey, is “huge progress.”