A Salvadoran immigrant is searched on the tarmac in Mesa, Arizona, before boarding an ICE repatriation flight in June 2012.Matt York/AP

In Guatemala City, the deportation flights come in twice a day, at 11:30 a.m. and 6:30 p.m. Nearly 50,000 Guatemalan nationals returned to their homeland on ICE Air in fiscal 2013; they landed at the Air Force airport, not the adjacent La Aurora International Airport, where baggage claim flat screens greeted me with Miley Cyrus’ “Party in the USA” when I visited a few months ago.

I traveled there to see why so many Guatemalan kids—8,068 Border Patrol apprehensions in fiscal year 2013, more than a 400 percent increase since fiscal 2011—have been trying to come to the United States on their own, and to find out to what happened to the ones who were sent back. For years, the Guatemalan government virtually ignored these repatriated children. It was up to them to figure out how to get home or find someplace else to live. Then, in 2012, a surge of unaccompanied kids from Central America arrived at the US border, and Guatemalan first lady Rosa Leal de Pérez turned child migrants into her signature issue.

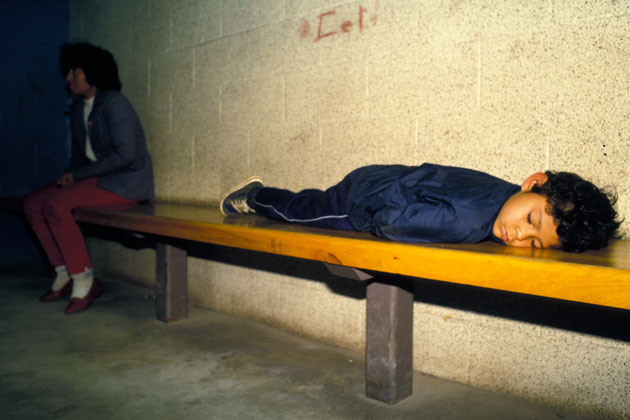

Now, when kids arrive without someone waiting for them or family nearby, they’re brought to Nuestras Raíces, a narrow colonial building not far from the Palacio Nacional. With its unmarked yellow facade and posters of smiling Mayan kids accompanied by biblical quotes, Nuestras Raíces is a cheery way station for the migrants, who are allowed to stay for up to 72 hours. They get to eat warm, familiar food, sleep in comfy-looking bunk beds, watch DVDs in an airy living room—and ponder what’s next: how to get home, but also what to do about paying off smuggling debts in the thousands of dollars, or whether to head north once again. One time, a seven-year-old girl showed up scared, saying she didn’t know anything about Guatemala. “But you’re from here,” said confused shelter employees. “What do you mean?” It turns out that the girl’s father was Guatemalan, but her mother was Salvadoran, and she’d been raised in El Salvador by her aunt. The US government had sent her to the wrong country.

The day I visit, Nuestras Raíces is spotless and empty. A staffer tells me that when parents do arrive to gather their kids, they are shown a video about migration and its effects. Many are Mayan, from communities in the western highlands, an area ravaged by the 36-year civil war that now struggles to combat narcoviolence. The government has plans to check in with the kids afterward, but no one knows how that’ll get funded. At least Guatemala has a couple of shelters in place; neither El Salvador nor Honduras has much of anything for kids deported from the United States. (One report, from 2008, claimed that in Honduras’ second-largest city, San Pedro Sula, “their common practice is to simply release children to their own devices.”)

Nuestras Raíces in Guatemala City only takes kids deported from the United States and northern Mexico—far enough away they have to be flown back to Guatemala. There’s another Nuestras Raíces shelter five hours away in the country’s second-biggest city, Quetzaltenango (known to locals by its ancient nickname, Xela), that receives thousands of kids deported by bus from southern Mexico. Xela is full of Mayans, backpackers, and NGOs, including Una Vida Digna, one of the partners in the Guatemalan repatriation and reintegration project managed by Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), a DC-based nonprofit that helps connect unaccompanied immigrant kids with pro bono attorneys. A two-person shop run by social worker Anna Aziza Grewe and Mayan spiritual guide Carlos Escalante, Una Vida Digna works to help deported Mayan youth fit back into their home communities.

A day after chatting over coffee and sweet rolls at Escalante’s house, on a rough cobblestone road a short walk from Xela’s center, he and Grewe invited me to a site visit in Totonicapán, a small city about an hour away. It was a cool, gray day, and upon arriving in town we walked five or six blocks from the bus terminal to a little shop surrounded by similar little shops: kites of all shapes and sizes framed the doorway, and a wall of sweet, salty, canned, caffeinated, and carbonated treats met us as soon as we stepped in. Behind the barricaded counter stood a short K’iche’ teen dressed head-to-toe in black, bangs slicing across his mahogany brow. His name was Luis, and months earlier he’d been deported from the United States.

Luis had gone to the United States with his uncle. After crossing near McAllen, Texas, they were separated and eventually caught. Luis spent three months in ORR custody, taking classes and putting up with Salvadoran boys he thought too “vain.” That’s where he heard about KIND, too, and how he got hooked up with Una Vida Digna following his deportation. Meanwhile, Luis’ uncle tried again, and made it, but Luis stayed behind in Totonicapán, where he now ran the uncle’s store.

As we sat on plastic stools behind the junk-food-laden counter and I asked questions about Luis’ hours at the store (open to close, 6:30 a.m. to 10 p.m.) and his take-home pay (nothing, though his uncle pays for him to be in the equivalent of middle school), Escalante sat to the side, his brow furrowing deeper the more Luis talked. “Don’t you have to bring something home to your mom?” he asked at one point. Luis blinked, and then talked about how his stepdad paid for everything at home, and how his uncle bought him whatever he needed outside of the store. “Even your underwear?” Grewe joked. Escalante, measured, asked, “Do you feel good about that?”

Escalante wanted Luis to take control of his life, to ask for a wage and to use that money to pay his own way, maybe get a room, think about the future. He talked to Luis about keeping an eye on which products moved and which gathered dust, about not letting friends take advantage of him, about shopping at the storehouses in Xela where coffee was cheapest. About doing all the things that would make this itty-bitty business at least profitable enough to keep Luis from deciding once again to risk it all and head north.

But if he did decide to try again, to leave behind Totonicapán and meet up with his uncle in New York? “We don’t measure our success on whether they stay or they go,” Escalante had told me earlier. There were just too many factors—substandard education, particularly—that kept rural Mayan kids from getting ahead.

With that in mind, the next day I made one more trip up into mountains. After heading to San Marcos, an hour and a half west of Xela, I hopped a chicken bus due north. We jostled along on a winding highland road, sardined six-across in the retired Blue Bird school bus. A Mexican gangster movie’s pinche cabrones blared over the speakers as we paused in a way station called Tejutla to load Mam women lugging bags full from the day’s market. A handful of hairpin turns later, the town was nothing but a dusty grid in the green valley below.

Soon enough, the bus shuddered to a stop on a curve carved out of the hillside. This was La Cumbre, the hamlet where Audelina Aguilar—a senior at San Francisco International High School, where I met several students who’d immigrated to the United States alone—and her brothers grew up. (Read more about Aguilar’s dangerous solo journey to the United States.) The heaving diesel coughed me out onto the road, and across the way her father, Don Israel, was leaning against a low wall, backlit by the afternoon sun. He’d been expecting us, sort of, for a week.

Israel’s wife, Doña Eva, made her way over to us with a little boy, about two years old, hiding behind her corte. As we settled into white plastic chairs on the patio between two buildings, the first a traditional, one-story whitewashed adobe home typical to the highlands, the other a two-story cinder block structure painted yellow with red trim, Israel nodded to the smaller house behind us. “That’s where we used to live,” he said. “Nothing but adobe.” On one side of the house, field mice had burrowed a bunch of holes in a corner.

It was already late in the day, and I knew I’d have to get back on the road soon if I had any chance of making the trip back to Xela. But I’d come to talk to them about what it was like watching four of their teenage children—Osvaldo at 15, Audelina at 14, Roberto at 16, and, most recently, Aníbal at 16—leave for the United States by themselves.

Corn, potatoes, and wheat filled the fields that sloped down away from the house and toward the horizon. Israel had been to the United States; he was in Alabama before the state adopted its draconian anti-immigrant law. But he was caught by local authorities in 2005, and after 20 days in jail, he found himself back in Guatemala. He worked in the fields and hauled construction materials, but with so many kids—when I asked how many, Israel and Eva went back and forth (four there, seven—no, eight—no, seven, here), laughing—it was hard to keep them all fed and clothed. As for whether they thought any more of their kids would attempt to go north in the near future, they couldn’t be sure.

“Who knows?” Don Israel said matter-of-factly. “The decision is theirs. Maybe if they get some help from there—” he said, nodding up at the sky, at an invisible but implied San Francisco—”because here money’s scarce. There isn’t any.”

This project was made possible by a fellowship from the French-American Foundation—United States.