Steve Helber/AP

This story first appeared on the ProPublica website.

After mass shootings, like the ones these past weeks in Las Vegas, Seattle and Santa Barbara, the national conversation often focuses on mental illness. So what do we actually know about the connections between mental illness, mass shootings and gun violence overall?

To separate the facts from the media hype, we talked to Dr. Jeffrey Swanson, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine, and one of the leading researchers on mental health and violence. Swanson talked about the dangers of passing laws in the wake of tragedy—and which new violence-prevention strategies might actually work.

Here is a condensed version of our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Mass shootings are relatively rare events that account for only a tiny fraction of American gun deaths each year. But when you look specifically at mass shootings—how big a factor is mental illness?

On the face of it, a mass shooting is the product of a disordered mental process. You don’t have to be a psychiatrist: what normal person would go out and shoot a bunch of strangers?

But the risk factors for a mass shooting are shared by a lot of people who aren’t going to do it. If you paint the picture of a young, isolated, delusional young man—that probably describes thousands of other young men.

A 2001 study looked specifically at 34 adolescent mass murderers, all male. 70 percent were described as a loner. 61.5 percent had problems with substance abuse. 48 percent had preoccupations with weapons. 43.5 percent had been victims of bullying. Only 23 percent had a documented psychiatric history of any kind—which means 3 out of 4 did not.

People with serious mental illnesses, like schizophrenia, do have a slightly higher risk of committing violence than members of the general population. Yet most violence is not attributable to mental illness. Can you walk us through the numbers?

People with serious mental illness are 3 to 4 times more likely to be violent than those who aren’t. But the vast majority of people with mental illness are not violent and never will be.

Most violence in society is caused by other things.

Even if we had a perfect mental health care system, that is not going to solve our gun violence problem. If we were able to magically cure schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression, that would be wonderful, but overall violence would go down by only about 4 percent.

Federal law prohibits people who have been involuntarily committed to a mental institution from owning guns. Is that targeting the right people?

The criteria we have are both over-inclusive and under-inclusive at the same time. They capture a lot of people who are not really at risk, at least not anymore. For instance, think about someone who had a suicidal mental health crisis 25 years ago, was involuntarily hospitalized, but now they’re recovered and fine, they haven’t had problems in years. They want to get a job as a security guard and they can’t because they can’t possess firearms.

Under-inclusive, because think about someone who’s in the middle of their first episode of psychosis, but hasn’t been treated. This might be a serious, dangerous mental health crisis—a person with paranoid delusions, believing that everyone else is out to get him, isolated, maybe drinking heavily—but he is not disqualified from going and purchasing any number of guns.

Then there’s another problem: Even if someone has a record of serious mental illness, these records might not actually make it into the background check system.

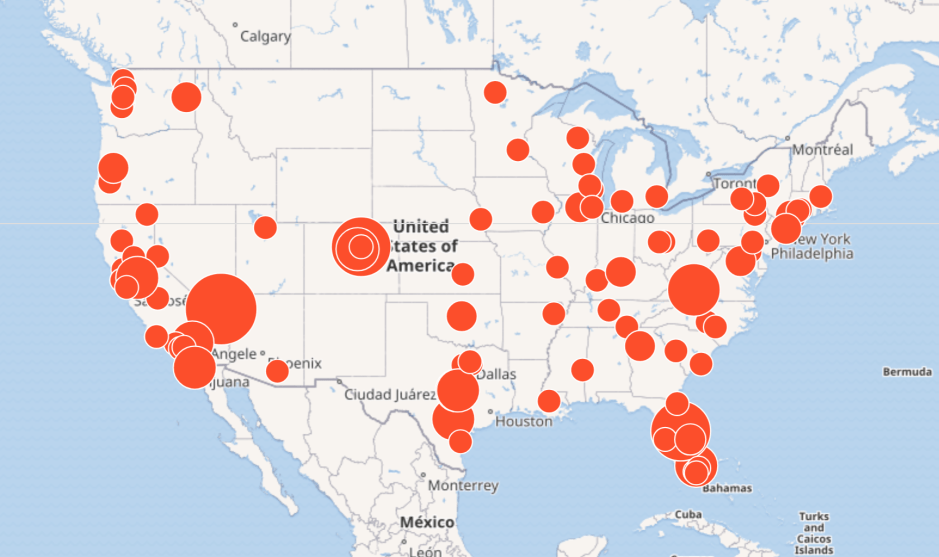

Reporting [of mental health records] is spotty. Mayors Against Illegal Guns put out this report [which found that, as of 2014, 12 states have still reported fewer than 100 mental health records to the national background check system.]

In one recent study, you found that adding more mental health records to the background check system can prevent some violence—but only a very small amount. Can you explain what you found?

The state of Connecticut provided a natural experiment. Prior to 2007, they didn’t report mental health records to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, and after that they did.

We compared two groups of people over eight years. Everyone had been hospitalized and had a major diagnosable psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia. One group had been hospitalized involuntarily, and was disqualified from buying guns. One group had been voluntarily hospitalized.

The criteria for involuntary commitment are intertwined with dangerousness and violence. Before Connecticut began reporting mental health records [to the background check system], people who had been involuntarily committed had a higher likelihood, month by month, of committing violence. After the period when the gun provisions were enforced, the difference went away—a 53 percent drop in their likelihood of committing a violent crime.*

So blocking people with serious mental illnesses from buying guns worked—but it didn’t have a huge impact. Adding the mental health records only prevented an estimated 14 violent crimes a year, or less than one half of 1 percent of the state’s overall violent crime. Why is that?

The people who were [actually disqualified from buying guns] were only 7 percent of the study population of people with serious mental illness—and only a very, very small proportion of people at risk of engaging in violent crime.

It’s like if you had a vaccine that was going to work against a particular public health epidemic, but only 7 percent of the people got the vaccine. It might work great for them, but it’s not going to affect the epidemic.

After the Santa Barbara shootings, the House of Representatives approved an additional $19.5 million to help states add more mental health records to the background checks system—a rare bipartisan move. Do we know if adding more records nationwide will have a big impact on violence?

[There’s an idea that] once we do that, it’s going to have a big effect. We haven’t done a lot of research on it.

When one of these mass shootings has occurred, there’s immediately a lot of attention and finger-pointing. Mental health becomes the one square inch of common real estate between people who want to reform the mental health care system, and gun rights people.

So, if our current standards for denying people gun rights based on mental illness doesn’t work very well, what would a better policy look like?

We want to focus more on behavioral indicators of risk, and not so much on “mental health” and “mental illness” as a category.

Even though the large majority of people with mental illnesses are never violent, there may be times in the course of illness and treatment when we do know that risk is elevated. One of those times is the period surrounding involuntary hospitalization. We think that if there are indicators of risk, that should be a time when firearms are removed—at least temporarily—with an opportunity for restoration of gun rights when the person no longer poses a public safety risk

There are lots of states when people are involuntarily detained for a 72-hour hold, never have a commitment hearing, and are not prohibited from firearms. People in that time frame, if guns were temporarily removed from them, that might have a big impact, particularly on suicide.

California Democrats are pushing a new state law that would create a “gun violence restraining order,” based on the model of a domestic violence restraining order. With a judge’s order, law enforcement would be allowed to temporarily take away someone’s guns. Is this a better model?

Yes. There are times when a family member, or people who know someone, can be legitimately concerned that person poses a threat. They might not have committed a crime. They might not even be having a mental health crisis. But if there were a way for family members to get law enforcement involved, that might actually save some lives.

In the Santa Barbara shooting, for example, the police were called. His family was concerned for him. But he didn’t meet the criteria to be involuntarily detained.

Gun violence restraining orders would allow people to say that someone seems dangerous, and have their guns temporarily taken away. How do you protect against someone abusing this law?

Connecticut, Indiana and Texas already have a dangerous person gun seizure law.With the gun violence restraining order idea, a judge would make that decision. There has to be evidence there. There is a constitutional right at stake.

You talk a lot about the tension between the way the media portrays mental health and violence, and the reality of the problem. If ‘mental health’ isn’t the key to violence in America, what is?

Violence is not distributed at random. If you look at the victims of homicide, for example—young African American men are far more likely to be victims of homicide.

We need to think of violence itself as a communicable disease. We have kids growing up exposed to terrible trauma. We did a study some years ago, looking at [violence risk] among people with serious mental illness. The three risk factors we found were most important: first, a history of violent victimization early in life, second, substance abuse, and the third is exposure to violence in the environment around you. People who had none of those risk factors—even with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia—had very low rates of violent behavior.

Abuse, violence in the environment around you—those are the kinds of things you’re not going to solve by having someone take a mood stabilizer.

What are the best ways of figuring out who is likely to become violent?

If someone has a history of any kind of violent or assaultive behavior, that’s actually a better predictor of future violence than having a mental health diagnosis. If someone has a conviction for a violent misdemeanor, we think there’s evidence, they ought to be prohibited [from owning guns.] Things like a history of two DUI or DWI convictions, being subject to a temporary domestic violence restraining order, or convicted of two or more misdemeanor crimes involving a controlled substance in a five-year period.

Those are the evidence-based recommendations of the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearms Policy [a group of mental health, gun violence, and legal experts who came together after the Sandy Hook shootings. You can also read their full federal policy recommendations and state policy recommendations.]

Most of our peer high-income countries can take a different approach. They can say, it’s just too dangerous for someone to have a personal handgun for their own protection. They broadly limit legal access to guns. That’s why they have lower homicide rates. What we try to do is keep the guns out of the hands of dangerous people, and that’s hard, because it’s hard to predict, and we have almost more guns than people.

What do we know about the risk factors for school shootings, in particular?

Katherine Newman’s book Rampage, which looks at school shootings, identifies five common factors. Every shooter in her study had some kind of “psychosocial problems,” which may include mental illness.

The other factors: Shootings tend to happen in smaller communities, where everybody knows everybody, and the person who does the shooting perceives himself as purely marginal. And there are cultural scripts that give them a model: the idea that if you go out and shoot people, you’re going to become this notorious anti-hero, on the front pages of every newspaper.

Then there’s the failure of surveillance systems—a teacher might have seen that the shooter was troubled, or it might be another kid. If everybody had been able to sit down together and connect the dots, they might have realized what was happening.

And the fifth factor is the availability of the weapons.

You’ve written a lot about the danger of making policy in the wake of high-profile tragedies. From the mental health perspective, what are the one or two worst laws pushed through in the wake of the Sandy Hook shootings?

One was the particular feature of the New York SAFE Act, that put in place mandated reporting by mental health professionals of clients who disclosed a risk of harming themselves or others. They were required to report the names of individuals to the police, so that the names could be matched to the gun permit database and their guns taken away. A lot of mental health professionals in New York [did not support this] because of the potential chilling effect. It might keep people away from help-seeking and inhibit their disclosures in therapy.

You’ve estimated that preventing mental health-related gun deaths could save 100,000 lives over a decade—but most of these would not be mass shooting victims, or even gun homicides.

Everyone has been through our National Mall and seen the Vietnam Memorial—what a sobering sight it is to look at 58,000 names, over a 10-year period of time, US military deaths. But if we were to build a monument to commemorate all the people who died as a result of a gunshot in the last 10 years, we would need a monument five times bigger than the Vietnam Memorial.

I’ve done these back-of-the envelope calculations. If you were to back out all the risk associated with mental illness that’s contributing to the 300,000 people killed by gunshot wounds in the last ten years, you could probably reduce deaths by about 100,000 people. Ninety-five percent of the reduction would be from suicide. Only 5 percent would be from reducing homicide.

Mental illness is a strong risk factor for suicide. It’s not a strong risk factor for homicide.

So if what matters is preventing suicides, why are we talking about guns?

Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Lots of times, it’s the impulsive action of a young person who’s intoxicated. There’s a huge possibility to prevent it. If a person survives a suicide attempt, there’s good evidence they’re unlikely to go and die from another suicide.

But the fatality rate for gun suicide attempts is just huge. You might survive an overdose. You’re not going to survive a shot to the brain at close range. At the time that someone is inclined to harm themselves, you don’t want them to have a gun. I’m all for improved access to mental health care. But part of the suicide prevention puzzle has to do with limiting access to lethal means.

I don’t think we’re ever going to live in a world where we’re not going to have troubled, confused, isolated young men. But we shouldn’t live in a world where men like that have very easy access to semi-automatic handguns.

So what are some of the ways to limit access to lethal means?

We’re not a country like the UK or like Australia, where we can say, “Let’s just limit legal access to handguns.” Guns are here to stay. Universal background checks, I would support. That, all by itself, wouldn’t be sufficient. We need to do something about limiting access to the guns people already have when they are inclined to harm others or themselves. In some states, 50 percent of people live in homes where they have guns already.

I have colleagues who are psychiatrists. When they see patients with serious depression, they counsel them about the danger of having a gun in the house. They have a conversation with family members. You can do a lot without invoking law, by talking to people about harm reduction and locking up guns. Getting family members to voluntarily store guns somewhere else.

In Switzerland, an army policy reform in the mid-2000s effectively cut in half the number of soldiers with guns stored in their homes. Researchers were able to show that this change in gun access resulted in a very significant decrease in the overall suicide rate.

We talked about why the current standards for disqualifying someone from owning a gun don’t work very well. But there’s also an interesting historical angle here. Why is the bar having been “committed to a mental institution”? Where does this standard come from?

The 1968 Gun Control Act—passed the year that Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated.

When the law was enacted, the mental health system was very, very different. We had massive numbers of people locked up involuntarily in psychiatric hospitals, often for long periods of time. In 1950, there were about 500,000 people in these institutions. Now, after deinstitutionalization, there are probably 50,000.

Fewer people now are disqualified on the basis of a mental health record. That’s not to say that the overall number of people disqualified from owning guns is lower. Some of the people who, in the old days, would have been disqualified because they were involuntarily committed—now some of them may have been disqualified due to a criminal record, and some would be incarcerated.

In Connecticut, we looked at 23,292 people with a history of serious mental illness. Only 7 percent of them were disqualified from owning guns because of mental health records. But 35 percent of them had a disqualifying criminal record.

But just because someone has a mental illness and they committed a crime—the illness isn’t necessarily why they did it. Among these people with serious mental illness, the risk factors for committing a violent crime appeared to have more to do with the overall risk factors for violence: being young, male, socially disadvantaged, and involved with substance misuse.

Correction 6/19/2014: An earlier version of this story misstated one of the findings of a gun study. After Connecticut added mental health records to its background check system, people who had been disqualified from owning a gun showed a 53 drop, not a 6 percent drop, in their likelihood of committing a violent crime.