My airplane home from Boston is delayed for takeoff, so the woman next to me pulls out her phones to get some work done. Like many of us, she has two—an iPhone for her personal life and a BlackBerry paid for by her employer. “It’s a dog leash,” she jokes. “They yank on it and I respond. If somebody from work emails me on Friday at 10 p.m., they’re pissed if I don’t write back in five minutes.” When I ask whether she ever just turns it off, she shakes her head in annoyance, as though I’d uttered something profane. “My team leader would kill me,” she says.

Cultural pundits these days often bemoan how people are “addicted” to their smartphones. We’re narcissistic drones, we’re told, unable to look away from the glowing screen, desperate to remain in touch. And it’s certainly true that many of us should probably cool it with social media; nobody needs to check Twitter that often. But it’s also becoming clear that workplace demands propel a lot of that nervous phone-glancing. In fact, you could view off-hours email as one of the growing labor issues of our time.

Consider some recent data: A 2012 survey by the Center for Creative Leadership found that 60 percent of smartphone-using professionals kept in touch with work for a full 13.5 hours per day, and then spent another 5 hours juggling work email each weekend. That’s 72 hours a week of job-related contact. Another survey of 1,000 workers by Good Technology, a mobile-software firm, found that 68 percent checked work email before 8 a.m., 50 percent checked it while in bed, and 38 percent “routinely” did so at the dinner table. Fully 44 percent of working adults surveyed by the American Psychological Association reported that they check work email daily while on vacation—about 1 in 10 checked it hourly. It only gets worse as you move up the ladder. According to the Pew Research Center, people who make more than $75,000 per year are more likely to fret that their phone makes it impossible for them to stop thinking about work.

Over time, the creep of off-hours messages from our bosses and colleagues has led us to tolerate these intrusions as an inevitable part of the job, which is why it’s so startling when an employer is actually straightforward with his lunatic demands, as with the notorious email a Quinn Emanuel law partner sent to his underlings back in 2009: “Unless you have very good reason not to (for example when you are asleep, in court or in a tunnel), you should be checking your emails every hour.”

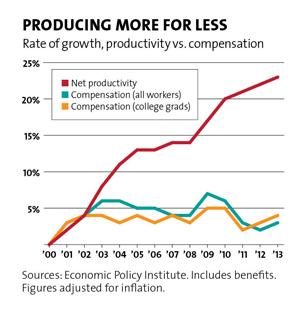

Constant access may work out great for employers, since it continues to ratchet up the pressure for turning off-the-clock, away-from-the-desk hours into just another part of the workday. But any corresponding economic gains likely aren’t being passed on to workers: During the great internet-age boom in productivity, which is up 23 percent since 2000, the inflation-adjusted wages and benefits for college graduates climbed just 4 percent, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

The smartphonification of work isn’t all bad, of course. Now, we tell ourselves, we can dart off to a dental appointment or a child’s soccer game during office hours without wrecking the day’s work. Yet this freedom may be just an illusion; the Center for Creative Leadership found that just as many employees without a smartphone attended to “personal tasks” during workday hours as those who did possess one. Even if you grant the convenience argument, the digital tether takes a psychic and emotional toll. There’s a Heisenbergian uncertainty to one’s putative off-hours, a nagging sense that you can never quite be present in the here and now, because hey, work might intrude at any moment. You’re not officially working, yet you remain entangled—never quite able to relax and detach.

If you think you’re distracted now, just wait. By 2015, according to the Radicati Group, a market research firm, we’ll be receiving 22 percent more business email (excluding spam) than we did three years ago, and sending 24 percent more. The messaging habit appears to be deeply woven into corporate behavior. This late in the game, would it even be possible to sever our electronic leash—and if so, would it help?

The answers, research suggests, appear to be “yes” and “yes.” Indeed, in the handful of experiments where employers and employees have imposed strict limits on messaging, nearly every measure of employee life has improved—without hurting productivity at all.

Consider the study run by Harvard professor Leslie Perlow. A few years ago, she had been examining the workload of a team at the Boston Consulting Group. High-paid consultants are the crystal-meth tweakers of the always-on world: “My father told me that it took a wedding to actually have a conversation with me,” one of them told Perlow.

“You’re constantly checking your BlackBerry to see if somebody needs you. You’re home but you’re not home,” Deborah Lovich, the former BCG partner who led the team, told me. And they weren’t happy about it: 51 percent of the consultants in Perlow’s study were checking their email “continuously” while on vacation.

Perlow suggested they carve out periods of “predictable time off”—evening and weekend periods where team members would be out of bounds. Nobody was allowed to ping them. The rule would be strictly enforced, to ensure they could actually be free of that floating “What if someone’s contacting me?” feeling.

The results were immediate and powerful. The employees exhibited significantly lower stress levels. Time off actually rejuvenated them: More than half said they were excited to get to work in the morning, nearly double the number who said so before the policy change. And the proportion of consultants who said they were satisfied with their jobs leaped from 49 percent to 72 percent. Most remarkably, their weekly work hours actually shrank by 11 percent—without any loss in productivity. “What happens when you constrain time?” Lovich asks. “The low-value stuff goes away,” but the crucial work still gets done.

The group’s clients either didn’t notice any change or reported that the consultants’ work had improved (perhaps because they weren’t dealing with twitchy freaks anymore). The “predictable time off” program worked so well that BCG has expanded it to the entire firm. “People in Brussels would go to work with a team in London that was working this way, and they came back saying, ‘We’ve got to do this,'” Lovich says.

For even starker proof of the value of cutting back on email, consider an experiment run in 2012 by Gloria Mark, a pioneering expert on workplace focus. Mark, a professor at the University of California-Irvine, had long studied the disruptive nature of messaging, and found that office workers are multitasked to death: They can only focus on a given task for three minutes before being interrupted. Granted, there isn’t any hard data on how often people were pulled away 20 or 30 years ago, but this level of distraction, she told me, simply goes too far: “You’re switching like mad.”

Mark decided to find out what would happen if a workplace not only decreased its email, but went entirely cold turkey. She found a group of 13 office workers and convinced their superiors to let them try it for a whole week. No digital messaging, full stop—not only during evenings and weekends, but even at their desks during the 9-to-5 hours. If they wanted to contact workmates, they’d have to use the phone or talk face to face.

The dramatic result? An enormously calmer, happier group of subjects. Mark put heart rate monitors on the employees while they worked, and discovered that their physical metrics of stress decreased significantly. They also reported feeling less plagued by self-interruptions—that nagging fear of missing out that makes you neurotically check your inbox every few minutes. “I was able to plan more what I was doing for a chunk of time,” one worker told her.

When the message flow decreased, so did the hectic multitasking efforts. Mark found that workers were flipping between windows on their screens half as often and spent twice as much time focusing on each task. Again, there was no decline in productivity. They were still getting their jobs done.

Mark’s and Perlow’s studies were small. But they each highlight the dirty little secret of corporate email: The majority of it may be pretty useless. Genuinely important emails can propel productive work, no doubt, but a lot of messages aren’t like that—they’re incessant check-ins asking noncrucial questions, or bulk-CCing of everybody on a team. They amount to a sort of Kabuki performance of work—one that stresses everyone out while accomplishing little. Or, as the Center for Creative Leadership grimly concludes: “The ‘always on’ expectations of professionals enable organizations to mask poor processes, indecision, dysfunctional cultures, and subpar infrastructure because they know that everyone will pick up the slack.”

Now, you could see these experiments as amazingly good news: It’s possible to rein in some of our counterproductive digital behavior!

But here’s the catch: Because it’s a labor issue, it can only be tackled at the organizational level. An individual employee can’t arbitrarily decide to reduce endless messaging; everyone has to do so together. “People are so interconnected at work, if someone tries to cut themselves off, they’re punishing themselves,” Mark notes.

Only a handful of enlightened firms have tackled this problem companywide. At Bandwidth, a tech company with 300-plus employees, CEO David Morken grew tired of feeling only half-present when he was at home with his six children, so he started encouraging his staff to unplug during their leisure time and actually prohibited his vacationing employees from checking email at all—anything vital had to be referred to colleagues. Morken has had to sternly warn people who break the vacation rule; he asks his employees to narc on anyone who sends work messages to someone who’s off—as well as those who sneak a peek at their email when they are supposed to be kicking back on a beach. “You have to make it a firm, strict policy,” he says. “I had to impose it because the methlike addiction of connection is so strong.”

Once his people got a taste of totally disconnected off-time, however, they loved it. Morken is convinced that his policy works in the company’s self-interest: Burned-out, neurotic employees who never step away from work are neither productive nor creative. It appears everyone wins when the boss offers workers ample time to unplug—tunnel or no tunnel.